Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

The buzz of a power saw drowned out excited shouting and screaming as Dale “Happi” American Horse, Jr. stood bound to a giant track hoe.

“Shame,” yelled one bystander to police. “SHAAAAAME!!!!!”

American Horse, 26, tensed up. The Lakota activist, a red bandana tied around his forehead, scrunched his shoulders and squeezed his eyes shut as a young sheriff’s deputy with unsteady hands angled a vibrating blade into the PVC pipe securing him to the construction equipment.

It was the last day of August and the resistance movement trying to halt the $3.8 billion Dakota Access Pipeline project had been mounting. That week’s A1 story in the Lakota Country Times, on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, reported that as many as 2,000 people from 95 tribal nations had descended on the ancestral lands of the Standing Rock Sioux in southern North Dakota.

American Horse, a Sicangu-Oglala Lakota, represented the symbolic significance of the gathering: a reunion of descendants of warriors who had defeated General George Armstrong Custer 140 years earlier. Chief American Horse the Elder, the activist’s ancestor, had been a notable figure in that victory.

Tim Giago started his first newspaper on the Pine Ridge Reservation. (Photo by Jenni Monet)

“Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ,” American Horse said as he was arrested. The phrase, loosely translated from Lakota, means “all are related,” a reference to the interconnected worldview of the Sioux. For readers of the Times, there was little need for these explanations. The weekly publication caters mostly to an audience who speak the language, understand Lakota values and history, and whose outlook is very different from their white neighbors’.

The next day, the newspaper featured on its front page a large color photo of American Horse attached to the heavy machinery. It was the third consecutive week that stories from Standing Rock had gotten page-one treatment. No other publication, with the exception of the Native Sun News Today in Rapid City, South Dakota, had covered the protests so extensively. The Sun and the Times are fierce competitors, engaged in an old-fashioned newspaper war. Yet from their perspective they share an even greater adversary: the mainstream media.

Over the course of nearly 40 years, a growing band of Lakota journalists has worked to fill a void left by the regional and national media. Few stories in mainstream publications emerge from on-the-ground reporting on reservations, and the rare stories that do typically focus on one of two themes: extreme poverty or chronic crime. For the Lakota press, the mission has been to give voice to those who had been long stereotyped, silenced, or dismissed.

The Sun sometimes has a harder edge than the Times, but otherwise they are very similar, in part because of the legacy of Tim Giago, 82, founder of the Native American Journalists Association and a mentor to generations of editors. The papers feature colorful banners and large photos. Pages carry titles such as “Voices,” for editorials, “Happy Ads,” for community announcements, and “Rez Happenings,” for events.

We still have beefs in Pine Ridge where it goes back to Red Cloud and Bull Bear fighting.”

Both papers are as much about Lakota death as they are about life. The obituary section in each represents a historical roadmap of families and the communities that connect them. The surnames tell stories of their own: Cross Dog, Has No Horse, Red Eyes, Iron Cloud. The Sun features these tributes in a section called “Journey to the Spirit World.” The Times’s section is headlined “The Holy Road.”

In the September 1 edition, an identical 350-word column appeared in the papers honoring the life of Fern Minerva Chasing Horse, born Fern Iron Elk of Lower Brule, South Dakota. A woman of Lakota traditions, she spoke the language and, according to the post, was known for her fry bread. The photo of Chasing Horse, a bingo fan, showed her in a pink blouse, the color of carnations. Among these details was also a nod to her relatives—a thorough list of parents, siblings, aunties, and cousins that signified the importance of kinship in indigenous society.

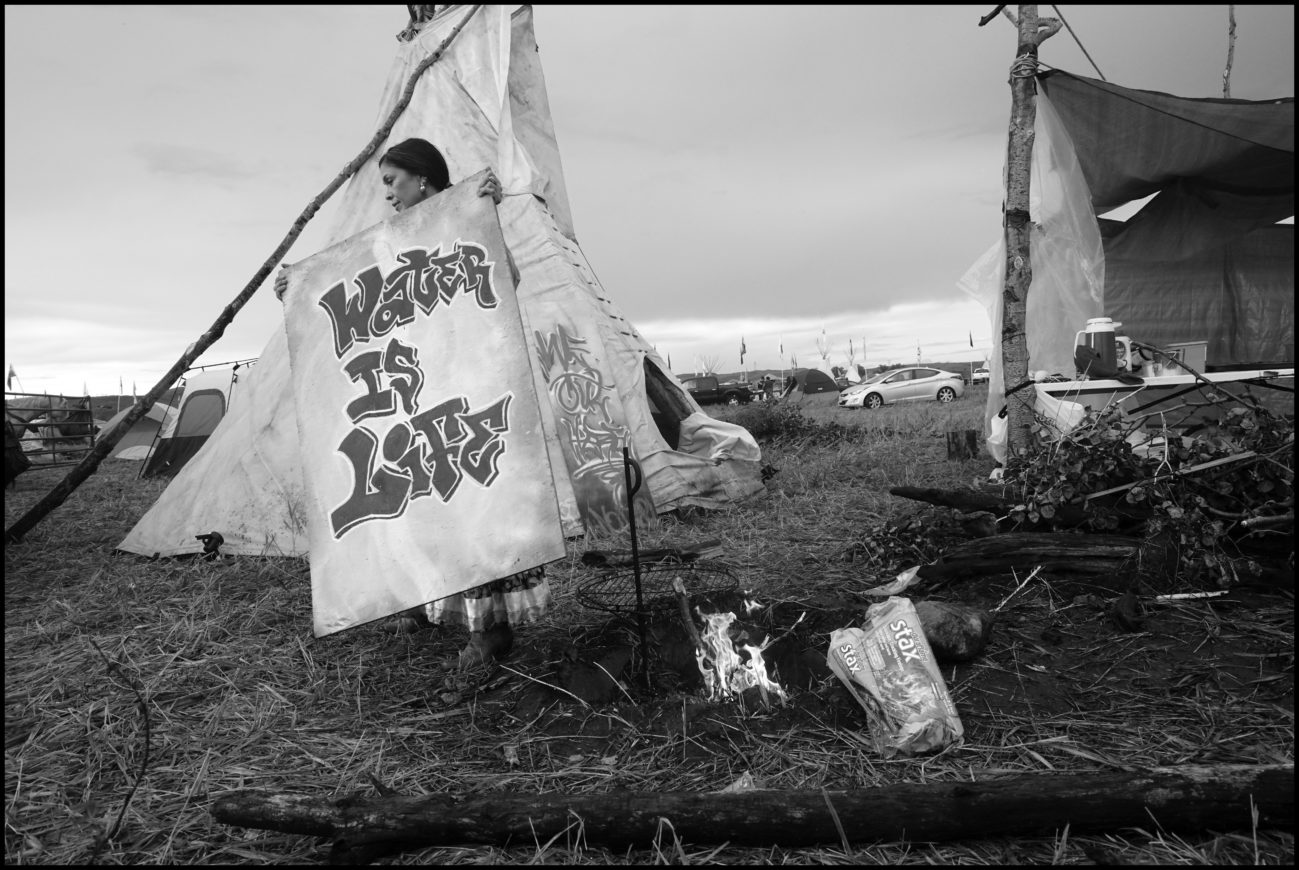

The morning of September 3 started out like any other day in the network of camps nestled along the banks of the Missouri and Cannonball Rivers. A water ceremony at dawn spilled over into communal breakfasts alongside campfires smoldering from the night before. As the morning dew burned away, the camps came to life.

The blunt sound of axes cutting through dry logs set off a rhythm that carried throughout the day. Horns blared from a caravan of arriving tribal leaders. Many had traveled hundreds of miles with gifts and flags branded with tribal seals. At some point, the whirring of drones could be heard overhead. Video taken from them appeared on social media, and chronicled how quickly the sprawling community of teepees and tents was growing. By year’s end, 12,000 people had arrived to take a stand, and flags displaying more than 300 tribal emblems flew along a dusty path leading to the shores of the Missouri River.

On this Saturday, though, the peace and sense of community were broken.

“CORPORATE TERROR SHAKES STANDING ROCK,” read the headline in the next edition of the Lakota Country Times. It was bylined Brandon Ecoffey, an Oglala Sioux tribal citizen and the paper’s editor. Private guards hired by Dakota Access had used attack dogs to drive anti-pipeline protesters away. Ecoffey’s lede zoomed in on what was central to the conflict: sacred sites and the Standing Rock protesters’ concerns over the oil company’s destruction of them.

“Just hours after the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe identified the location of multiple historical and culturally significant sites, workers for the Dakota Access Pipeline seemingly went out of their way to erase their existence,” read Ecoffey’s first paragraph.

That piece of the narrative was buried by almost all who covered the dog attacks—even by Democracy Now!, the news broadcast largely credited with drawing attention to the Standing Rock story, and The Bismarck Tribune, North Dakota’s leading chronicler of the pipeline battle.

Protestors in Pierre, South Dakota, in March. (Photo by Jenni Monet)

The Native Sun also provided deep context to the clashes. Its reporter quoted the Red Warrior Camp, a confrontational faction of the anti-pipeline movement. She noted that the dog attacks occurred on the anniversary of the 1863 Whitestone Hill Massacre, when more than 300 indigenous Dakota men, women, and children were killed by the US military on the banks of the Cannonball River.

“Without having context or knowledge of historical relevance within our tribal communities, you miss a lot of the important points,” Ecoffey explains. “And when you look at hyperlocalized news, Native journalists, we’re the only ones to really capture that.”

After the dog attacks, much of the mainstream coverage during the months-long demonstration was tonally lopsided. Protesters were described as “unlawful.” The unasked question was, according to whose laws? The state’s? The county’s? Or was it the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie? That pact granted vast tracts of land to the Lakota Sioux, but it was amended—under duress, many insist—after General Custer’s death. The loss of land was very much top of mind for the protesters, also known as water protectors, as they stood up to military-style policing.

“There’s a lot of things that white people don’t want to talk about,” says Giago, owner of the Native Sun News Today. “We remind them of things they’d rather forget.”

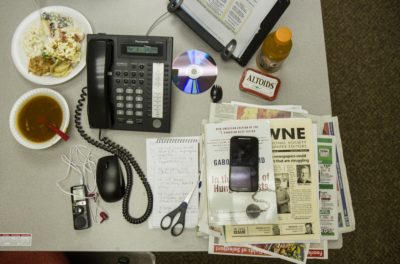

Ernestine Chasing Hawk, editor of Native Sun News Today, and her desk at the newspaper

Take Mount Rushmore. The New York Times Magazine in March featured a story about a family vacation to the monument in an SUV. But the view of the same location through a Lakota lens is a sharp reminder of hardship and loss. The carved faces of American presidents don’t represent tourism, but the desecration of the sacred Black Hills, taken from the Sioux. Lincoln’s inclusion in the monument is especially unsettling. He ordered the hanging deaths of 38 indigenous Dakota men, the largest known execution ordered by a US president in American history.

Giago, an Oglala Sioux, is considered by many to be the godfather of the Native American press, and over many decades he has started, traded, shuttered, and sold four publications. He has hired dozens of aspiring Native American journalists, including Amanda Takes War Bonnet, who worked her way up from janitor to managing editor at one of his papers. She later went on to start the Lakota Country Times.

Giago’s approach to reporting has become the unofficial standard, and what mattered to him most from the start was authenticity. Quotes from tribal citizens went unedited, regardless of their length or grammar, and almost every story attempted to draw connections between the present and the cultural or political past.

Giago got into journalism when he became a columnist for the Rapid City Journal in 1979. He often wrote about his boyhood abuse at the Holy Rosary Mission School on the Pine Ridge Reservation. “Catholic bashing,” was how his editor described the boarding school memoirs, Giago recalls. He wrote about other injustices against the Lakota, too. At the time few, if any, Native American journalists were working in the newsrooms of mainstream newspapers. Giago’s stories made the Journal’s mostly white readership uneasy, but he gained an immediate following among the region’s tribal citizenry. For the first time, Lakotans could read about themselves in ways that weren’t tied to alcoholism, prison, or welfare.

Giago was told by Journal editors to tone down the copy or risk losing his column. Feeling censored, he walked away. In 1981 he launched his first newspaper, the Lakota Times. (No relation to the Lakota Country Times.) Historically, tribal governments had financed and staffed small community papers. He says he became the first publisher of an independently owned newspaper solely focused on reservation life.

The Lakota Times was born during a near-civil war across the Pine Ridge Reservation, the aftermath of the American Indian Movement’s 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973. Just over 80 years before, Sioux men, women, and children gathered at Wounded Knee and were massacred by US soldiers in large part vengeful over Custer’s defeat. Many Lakota supported AIM, which demanded, with raised fists, that the US government recognize and act to address civil rights violations of Native Americans.

Giago, along with others, had a very different view. The historic hamlet of Wounded Knee was Giago’s hometown, and when he returned to the area after several years on the West Coast, he felt strongly that the insurrection had damaged his community and brought its own host of problems to the reservation.

“The Associated Press, whenever they wrote about Wounded Knee, they would describe it as an ‘uprising,’ ” says Giago, who took offense at the term and called the AP to complain. “I said, ‘The people of Wounded Knee did not rise up. They were taken over by an outside group. Their homes were destroyed. Their trading post was destroyed.’ ”

The ongoing divisions in the Pine Ridge community about the legacy of Wounded Knee were rarely, if ever, reported in the mainstream press. But Giago was vocal about his views in the pages of the Lakota Times. His makeshift newsroom, in a former beauty salon, was firebombed and its windows shot out by gunmen. He says he received death threats because of his conservative views on the American Indian Movement. “You know if they had attacked a paper in Lemmon or Winner, it would have been news all over the state,” says Giago, referencing two predominantly white towns bordering the reservation. “We didn’t get a peep.”

Tim Giago, owner of the Native Sun News Today, has been a mentor to generations of editors. (Photo by Jenni Monet)

Giago eventually retired, but then launched the Native Sun in 2009 in Rapid City. Two years later, Ecoffey responded to an ad for a reporter position. The child of a Bureau of Indian Affairs superintendent, Ecoffey was once one of Pine Ridge’s proudest sons. After attending Dartmouth College, he returned to work for the area chamber of commerce, coached basketball, and tutored reservation youth. He also developed a gambling problem and cocaine addiction, and ended up spending three and a half years in prison on federal drug charges. As part of his transition to a halfway house, he needed a job.

As Ecoffey, 33, and I walked down a graffitied alley in downtown Rapid City, past a mural of the great war chief Sitting Bull, he explained how prison had taught him not to judge, especially among his fellow Lakotans, a group that has one of the highest incarceration rates in America. Ecoffey says even his own trial was covered poorly in the local mainstream press. These experiences fueled his desire to document the first drafts of history as they relate to Lakota society.

“To write about us, you need to be able to relate to the hardships that people have,” he says. “I understand that our people have been through struggles. Just the understanding of the effects that has on a person’s life, I think it helps to really capture the story.”

For a year, Giago mentored Ecoffey and edited his work. But like the ebb and flow of Giago’s newspaper holdings, the Lakota publisher’s relationships with those he groomed was complicated. Ecoffey took the lessons he’d learned at the Sun to the competition—the Lakota Country Times.

Last November, five years after Ecoffey’s defection, the simmering war between the two papers escalated over the election of the president of the Oglala Sioux tribe. The incumbent, John Yellow Bird Steele, lost and blamed Native Sun News Today. The Sun had published a story disclosing a whistleblower’s allegation of financial improprieties by the Steele administration. Among the accusations were questions about whether Steele had contributed too much money to support the Standing Rock protests. The article’s author, Ernestine Chasing Hawk, wrote that the Lakota Country Times had refused to touch the story. “The Times receives money from the tribe as their official newspaper and is not allowed to publish negative stories that reflect badly on the tribe,” she wrote.

There’s a lot of things that white people don’t want to talk about. We remind them of things they’d rather forget.”

The tribal government pays the Times to print weekly government minutes and community notices. But Connie Louise Smith, the paper’s owner, says it is not prohibited from covering anything, and that the aim is to promote family literacy and live by the newspaper’s motto: “Truth, Integrity and Lakota Spirit.”

Ecoffey says the dispute is typical of Indian country politics. “We still have beefs in Pine Ridge where it goes back to Red Cloud and Bull Bear fighting,” he says, alluding to Lakota chiefs of five generations back. “Those political realities still play themselves out in policy decisions made by tribal leaders today.”

Two weeks after the tribal election, on the evening of November 20, both the local and national media were absent when police waged a brutal attack on the protesters at Standing Rock. This time there were rubber bullets and water cannons—particularly devastating in freezing temperatures. The world learned about it through Facebook Live streams. The national press had been slow to cover previous incidents at Standing Rock, and even slower to grasp the complex issues central to the protest movement—treaties, sovereignty, and environmental racism. But now these events were impossible to ignore. And, finally, some reporters began to incorporate Lakota Sioux perspective into their stories.

On December 4, the day the US Department of the Army denied a permit to the operator of the Dakota Access Pipeline, CNN correspondent Sara Sidner went on air to discuss the “black snake,” the term the Lakota use to describe the project. The snake, if not stopped, would cause great destruction to Mother Earth, she said, explaining a Lakota prophecy in detail.

I later learned that Sidner had received talking points about Lakota culture from a Native-American editor at the news website Indian Country Today, which was owned by Giago before he sold it in 1998 to the Oneida Nation in New York.

“They let us educate them,” says Waniya Locke, who lives on the South Dakota side of the Standing Rock Reservation. “For the first time, it felt like our voices were heard.” She had protested against the Keystone XL Pipeline in 2015, and considered coverage then to be lazy and too focused on one storyline—white ranchers and Native Americans teaming up to fight big oil. “It was about so much more than that,” she sighs.

Almost immediately after taking office, President Trump signed executive orders allowing the Keystone and Dakota Access Pipelines to proceed, and on February 23, police removed the protesters from the main campsite. Within a few days, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, visited Standing Rock and criticized the state’s use of chemical sprays, rubber-coated bullets, tanks, and concussion grenades against unarmed people.

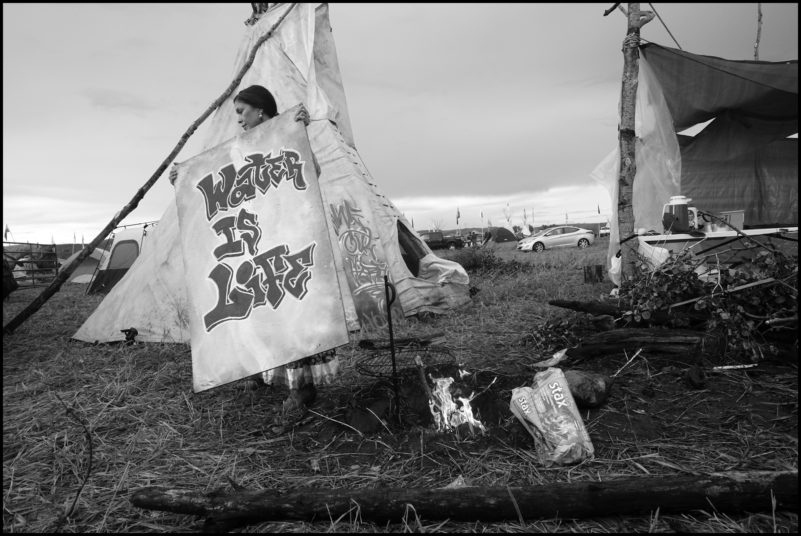

Photo by Larry Towel / Magnum Photos

“I’ve never experienced being shot by a rubber bullet during my protests in the Philippines,” Tauli-Corpuz told the Lakota Country Times, referring to her home country. “I thought that there was really an excessive use of force.” She expressed disappointment that the Standing Rock Sioux tribe had not been consulted when the decision was made to move the pipeline away from municipal wells serving Bismarck’s mostly white population and closer to the Sioux. “It’s very discriminatory,” Tauli-Corpuz said. “Even without consulting the tribes . . . they just decided to put the pipeline under their sacred sites.”

The UN expert’s visit was a historic day for Standing Rock, and for that matter, North Dakota. The Aboriginal Peoples Television Network sent a camera crew. The humble tribal radio station, KLND, broadcast live from the scene. The Washington Post and the AP published short stories on the visit, but The Bismarck Tribune only published a notice before the event, and most other media outlets ignored it.

While the protests have died down, both sides are regrouping for the next battle. Many activists are planning to turn their attention back to the Keystone XL Pipeline. The government is making its preparations as well: In mid-March, South Dakota Governor Dennis Daugaard signed a law imposing stricter penalties for protesting. “It is very likely that people from across the country will come to South Dakota to join our tribal members in exercising their right to communicate their concerns, and the belief that the pipeline is a threat to the welfare of tribes,” he explained.

The Lakota Country Times, under Ecoffey’s byline, published a story criticizing the governor for not consulting the state’s tribes before signing the law. The regional AP pointed out that the governor had not consulted with the tribes, but didn’t quote a Native American.

“For us in Indian Country, this law is obviously directed towards us. It’s basically threatening to criminalize ‘water protectors,’ ” Ecoffey says. “It’s up to us to bring light to these kind of narratives.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.