Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

The release of the almost-complete report by Robert Mueller is an opportunity to discuss a couple of words in it, and the sometimes subtle differences that can skew readers’ opinions of the results.

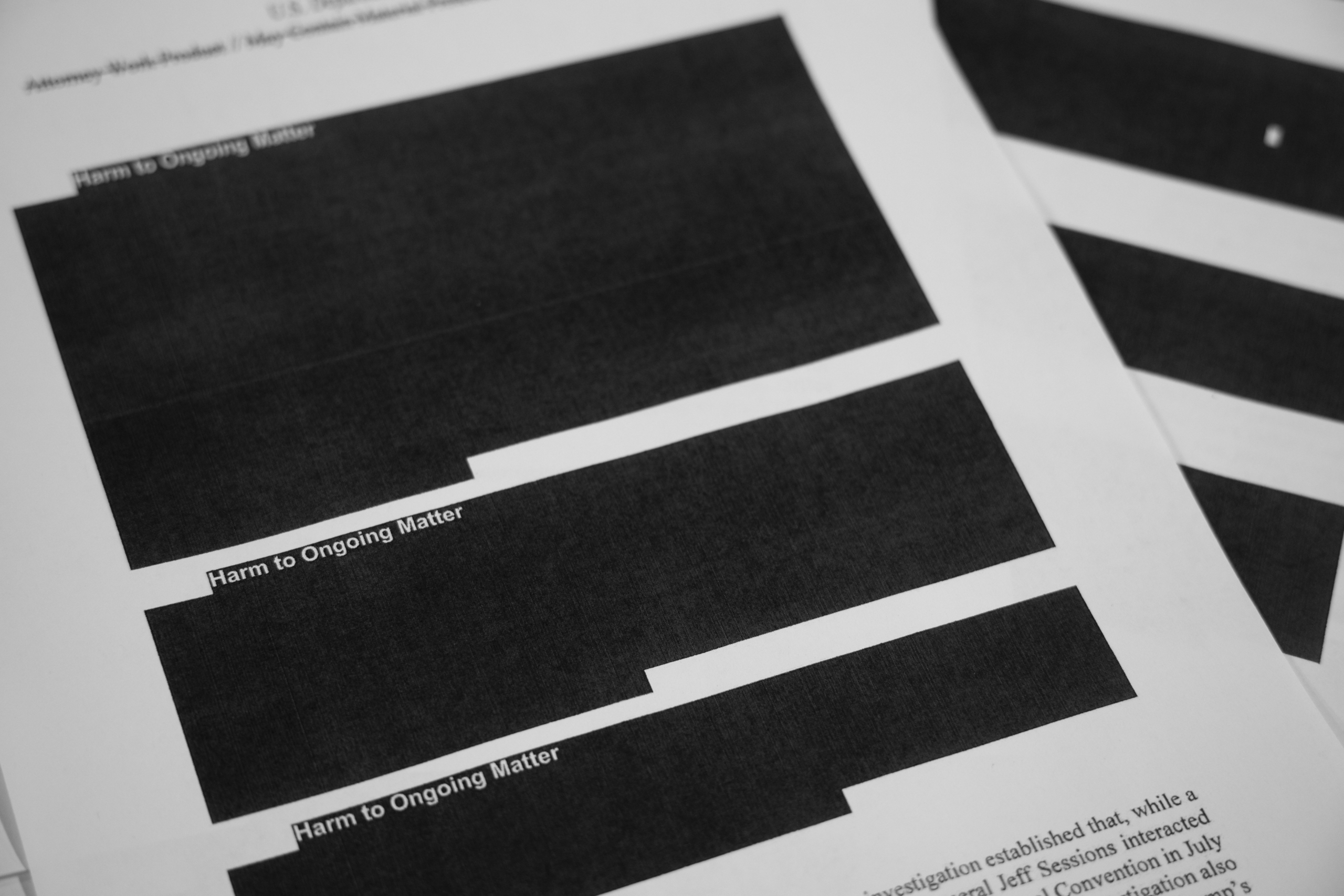

The report was “almost complete” in that portions of it were obscured, or “redacted.” Some say the report was “censored,” but “censored” and “redacted” conjure different motives.

ICYMI: The visual power of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

As Ben Zimmer wrote in The Wall Street Journal last week, “redact” once meant simply “edit” or “organize.” (In French, “un rédacteur” is an editor, usually a news editor.) The original meaning of “redact” was “bring together” or “combine,” the Oxford English Dictionary says, and traces the word to about 1475. But “redact” dropped from sight in the mid-18th century, and reemerged in the early 19th century to mean “To put (writing, text, etc.) in an appropriate form for publication; to edit.” As Zimmer said: “The meaning next narrowed from general editing to focus on abridgments during the revision process. The idea of removing passages of text became the primary one, especially when it was applied to the censorship of official documents.”

Merriam-Webster has two relevant definitions of “redact”: “to select or adapt (as by obscuring or removing sensitive information) for publication or release” and “to obscure or remove (text) from a document prior to publication or release.”

Note that Zimmer used “censorship” to describe the type of “redaction” taking place in official documents. But “censors” have slightly different duties than “redactors.” Merriam-Webster’s first definition of “censor” is “a person who supervises conduct and morals.” Most “censors” are looking for material that is morally objectionable or harmful to the entity doing the “censoring.” That is more in line with the original “censors,” magistrates in ancient Rome who both took the “census” of citizens and supervised public morals. In the mid-17th century, a “censor” was “An official in some countries whose duty it is to inspect all books, journals, dramatic pieces, etc., before publication, to secure that they shall contain nothing immoral, heretical, or offensive to the government,” the OED says. The verb “censor” didn’t show up until the mid-19th century, with specific duties for “the control of news and the departmental supervision of naval and military private correspondence (as in time of war).”

Put another way, a “censor” seeks to protect information that is morally or politically objectionable. A “redactor” has different responsibilities. In the Mueller report, Attorney General William Barr had four categories of “redactions”: to protect secret grand jury testimony, “ongoing matters,” classified material, and “personal privacy.”

The “unredacted” parts of the Mueller report use the word “surveillance” four times. Three instances refer to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act or Court, which has the authority to issue warrants to wiretap or eavesdrop on subjects of investigations. The fourth appearance of “surveillance” is in a quote from a tweet from President Trump on Aug. 24, 2018, in which he assailed “FISA abuse” and “illegal surveillance of Trump Campaign.”

The word “spy” also appears four times in the report: once quoting a Reuters headline; once quoting a New York Times headline; once quoting Trump’s former campaign manager, Paul Manafort, as saying that he did not believe a Ukrainian-Russian business associate “was working as a Russian ‘spy’”; and once saying that the former Trump campaign official Rick Gates suspected that same Ukrainian-Russian businessman “was a ‘spy,’ a view that he shared with Manafort.” The report never used it in the context of “surveillance”

As in “redact” and “censor,” the difference between “surveillance” and “spying” is often in the intent. According to a M-W post on “surveillance,” “Surveillance means ‘close watch kept over someone or something (as by a detective).’ By contrast, spy means ‘to watch secretly usually for hostile purposes.’”

The word “surveillance” first appeared in English in the early 19th century as a noun, the OED says, arising from the French verb “surveiller,” to watch over. The OED says that “surveillance” first meant “Watch or guard kept over a person, etc., esp. over a suspected person, a prisoner, or the like,” and “spying, supervision.” The verb “surveil” did not appear until 1960, the OED says, though M-W traces it to 1884.

By contrast, the verb “spy” appeared around the beginning of the 14th century, the OED says, to mean “To watch (a person, etc.) in a secret or stealthy manner; to keep under observation with hostile intent; to act as a spy upon (one).” Stealthy and hostile are connotations implied in “spy,” but “surveillance” has a cleaner, less hostile vibe. Legal government “surveillance” may indeed be “spying,” but if it’s legal it might be considered “hostile” only by its target.

“Spy” is related to the slightly older word “espy,” which meant “to act as a spy upon.” Nowadays, though, “espy” is usually used to mean “to catch sight of,” with no hint of nefariousness.

The nuances of “redact/censor” and “surveillance/spying” are important to remember when writing about politically fraught topics. One person’s “surveillance” or “redaction” might be another’s “spying” or “censorship.” It might be hard to “espy” which one to use in which context, but keeping in mind the motives or legalities of the actions can help keep the discussions transparent.

ICYMI: Sarah H. Sanders admitted she misled the media in the Mueller report

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.