Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Last week, in honor of summer, we talked about “thongs” and “bikinis.” This week, not only do we have the first full week of summer, we also have the dedication of the newly expanded Panama Canal.

So it seems appropriate to talk about “Panama” hats, the lightweight straw hats that show up in northern climes during the summer.

The story many people have heard is that these straw hats were made in Panama and sold to the travelers who were crossing the isthmus before the canal was built.

That’s only partly true. The hats were sold in Panama, but they were usually made in Ecuador, from the dried, palmlike fronds of the jipijapa or toquilla plant, which is native to Ecuador (and now cultivated elsewhere).

So how did they end up being called Panama hats? The best explanation comes from Brent Black and the Panama Hat Company of the Pacific. The Ecuador hats had been made for centuries–some say the Incans were the first to make them–as breathable, lightweight protection from the sun, often called “toquillas.”

But some smart Ecuadorean merchant, probably Manuel Alfaro, knew there was a larger market in Panama, the narrowest passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

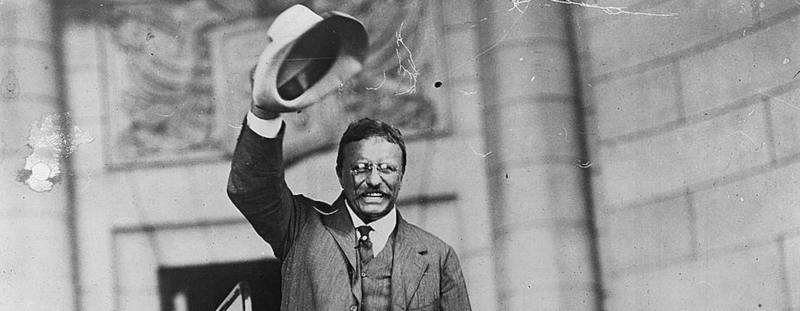

Some of the hats ended up in Europe, where Napoleon is said to have sported one. But the real explosion seems to have been with the construction of the Panama Canal itself, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Photos of workers wearing the hats fed their popularity, especially because President Theodore Roosevelt adopted them during his visit to the canal site in 1906.

Oxford English Dictionary traces the first use of “Panama hat” to 1834, in a British novel, Peter Simple, about a young midshipman in the Napoleonic wars. The author, Frederick Marryat, was himself a naval officer, though there’s no indication that he was ever in Panama or Ecuador.

In addition to introducing “Panama hats” to English, Marryat also developed a maritime flag code for merchant vessels, introduced in 1817. Unlike the hats, his code didn’t last long: It was supplanted by an international code in 1870, about the time “Panama hats” were coming into vogue.

“Panama” hats are favored mostly by men, but another summer staple is an equal-opportunity fabric. We’re talking about “seersucker,” a thin fabric that has alternating stripes, often light blue and white, with a slightly puckered look to them.

If you troll the internet too much, you can find all sorts of stories on how “seersucker” came about. Fashion sites will tell you that Brooks Brothers and Haspel both claim credit for popularizing seersucker in the United States, and in one advertisement Brooks Brothers claims to have made seersucker coats as early as 1832. There is even a story that a fabric resembling “seersucker” was invented by Sears, Roebuck and Company, but people considered it such a cheap fabric that people who wore it were called “Sears suckers.”

But “seersucker” was not invented here at all. Appropriately enough, it originates in the hot regions of Persia, where a light, striped linen fabric was called “shir u shakar,” which translates literally to “milk and sugar.” The British colonials adopted it for their clothing to help them deal with the heat.

That would imply that “seersucker” was brought to the West sometime after the East India Company was formed, in the early 17th century. But the first written reference doesn’t show up until well into the 18th century. According to Oxford English Dictionary, a 1925 issue of Maryland History Magazine cites a 1722 reference to “seersucker”; a 1736 reference in The Virginia Gazette says that a servant woman ran away and took “a Seesucker Gown.”

Regardless, “seersucker” became very popular in the 1920s, then fell out of favor until the ’60s or so. The New York Times, where I worked for 25 years, used to observe “Seersucker Day” on the first day of summer, when dozens of people would come to work dressed in seersucker suits, dresses, skirts, ties, robes, and sometimes fanciful items like masks.

Sen. Trent Lott established “Seersucker Thursday” for Congress in the ’90s, often now called National Seersucker Day. It was on June 9 this year, which seems too early, since “seersucker” is a summer fabric.

For once, Congress is fashionable ahead of its time.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.