Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

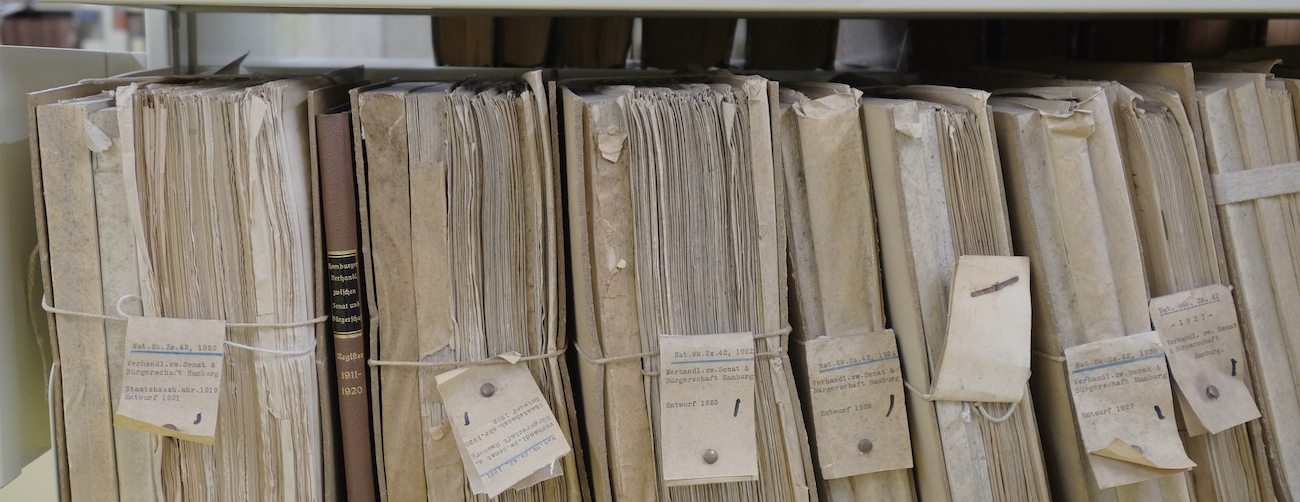

Let’s assume your doctor has not gone totally electronic. If you walked into the doctor’s office and, behind the receptionist, saw a cabinet containing rows and rows of fat manila folders, each with some letters or numbers on the spine, you would probably think of it as a “filing cabinet,” or as shelves filled with “files.”

When you went into the doctor’s consultation room, on the desk would probably be a manila folder with your medical history in it. The doctor would refer to it as “your file.”

But really, it’s your “dossier.”

Even if you’re not a spy (or Donald Trump), you have “dossiers.” You just didn’t know it.

Before news reports revealed the (maybe) existence of a (maybe) explosive “dossier” that the Russians (maybe) had on Trump, the word “dossier” had appeared in Nexis barely 150 times in the previous month. But within a week, “dossier” had appeared more than a thousand times, nearly always in the company of “Trump.”

A “dossier” is simply “a collection of documents concerning a particular person or matter,” as Webster’s New World College Dictionary defines it. In other words, “dossier” is just a fancy word for “file.” But thanks to World War II, the Cold War, and spy novels, “dossier” seems to be the preferred term when espionage or intrigue is involved.

This Google Ngram of the appearance of “dossier” in books shows the first spike coinciding with the post-World War I period (starting about 1923), with a huge spike in the early 1960s, concurrent with the rise of communist China, the division of Berlin, and the Cuban missile crisis. “Dossiers” fell off in the early 21st century, but since the database goes only to 2008, it’s a mystery what has happened since.

As Merriam-Webster explains:

Gather together various documents relating to the affairs of a certain individual, sort them into separate folders, label the spine of each folder, and arrange the folders in a box. “Dossier,” the French word for such a compendium of spine-labeled folders, was picked up by English speakers in the late 19th century. It comes from “dos,” the French word for “back,” which is in turn derived from “dorsum,” Latin for back.

The Oxford English Dictionary says “dossier” entered English in 1880, from the French sense of a “ ‘bundle of papers’, which from their bulging are likened to a back (dos).”

So the word “dossier” has more in common with your doctor’s collection of files than with the intelligence community’s secret information.

In some situations, though, “dossier” is a technical term with specific meanings. A website offering training on compliance with regulations covering medical devices, for example, offers a rather dense explanation of the difference between a “technical file” and a “design dossier.” (The “design dossier” is far more detailed than the “technical file.”) Web design might call for a “dossier” of all the styles, templates, etc. used to produce a website.

No dictionary specifies that a “dossier” has anything secret, intriguing, or even special in it. It’s just a “file” containing detailed information. We all have “files,” kept about us by government, commercial, and medical entities; and kept by us for finances, contacts, medical records, etc. Few of us would call any of those “dossiers.”

In so many ways, “dossier” is just jargon. But it has that sense of something secret, hidden, forbidden, explosive, intriguing. Most of the time, the connotation is negative—if someone has a “dossier” on you, it’s probably not because of your (alleged) good deeds.

For journalists, calling something a “dossier” falls into the spin trap, even if that’s how the intelligence community characterizes it. “The Russians may have a secret file on Donald Trump” is just as good, unless you are a spin doctor.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.