Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

When the Wicked Witch flies over Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz, spelling out “Surrender Dorothy” in broom smoke, the terrified and nonplussed residents cry to one another: “The wizard will explain it!” and “To the wizard!”

Dictionaries are our wizards, places we run to when we encounter scary or unfamiliar words or terms.

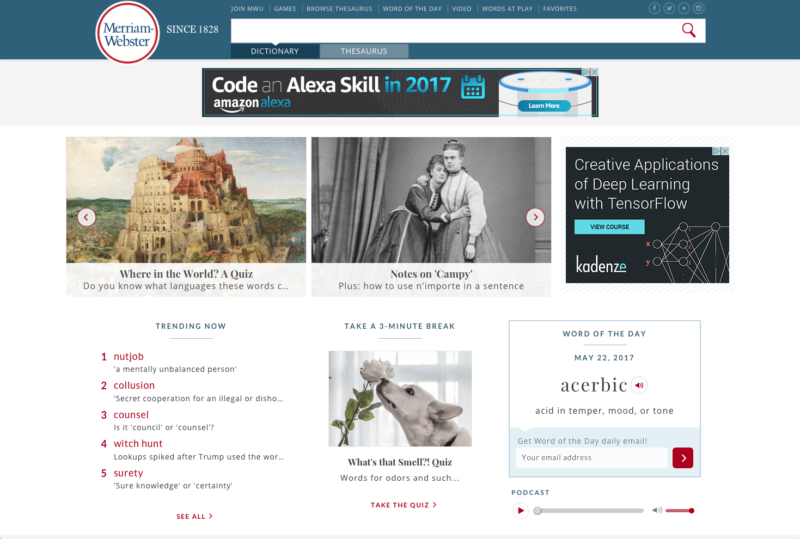

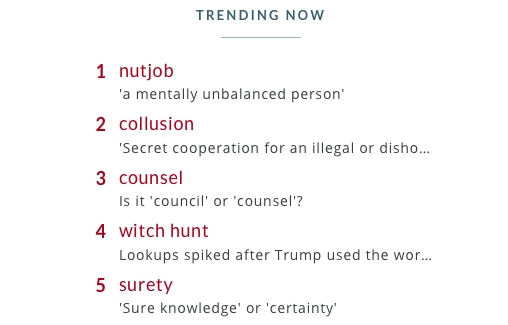

To show how this plays out in real life, just visit the homepage of Merriam-Webster.com. Here’s what it looked like on Monday morning.

Under the “trending now” column is the previous week’s news, laid out for all to see.

Lookups for “nutjob” spiked 173,750 percent after President Trump used it to describe the fired FBI director James Comey. (The New York Times spelled it “nut job,” an alternative spelling.) Lookups for “collusion” “snuck to the forefront of our lookups on May 17, after it was used repeatedly by Donald Trump in response to questions at a press conference,” Merriam-Webster said. Lookups “for both council and counsel spiked on May 18, after President Trump used the spelling councel in a tweet”—for the second time in two weeks. (Since “councel” isn’t in the dictionary, seekers are presented with a list of spelling suggestions, topped by “council,” “conceal,” and “counsel.”) Similarly, “witch hunt” jumped to the top after Trump used it in reference to investigations of Russian interference in the 2016 election; ditto “surety,” after Trump used it in his speech to Coast Guard Academy graduates.

RELATED: How to remember who vs. whom

Pay no attention to that spiking percentage behind the curtain. It’s a humbug. If one person has looked up “nut job” in a certain period and 173,749 look it up in another, there is your percentage jump. It’s fire coming out of an ephemeral image, and it is likely to soon return to its plain, ordinary, ignored life. It reflects a moment in time, to be sure, but people have a short attention span, and will soon look up something else.

The people of Emerald City ran to the wizard because they believed him to be the authority on everything. So it is with dictionaries. As Kory Stamper, a Merriam-Webster lexicographer, writes in her wonderful new book, Word By Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries, “the general public—particularly in America—has been trained to think of the dictionary as an authority, and so what ‘the dictionary’ says matters.” When people come across a word they’re not sure of, or want to provide a context for, they run to the dictionary. As Stamper wrote, “scanning through the top lookups on any dictionary website shows that most words that interest us do so because we are unclear about the thing to which they are applied or we want to use the definition to run the litmus test on the situation, person, event, thing, or idea that that word was used of.”

And just as the wizard provides no wizardly solutions but provides answers that reflect on the characteristics of the people asking the question, so do dictionaries act as reflectors: They report language as people use it, but they don’t have magical powers.

RELATED: One word you thought the TSA would never use

As a case in point, Stamper cites the American Heritage Dictionary’s Usage Panel, a group of about 200 people who are asked each year if they would find certain things acceptable in speech or writing. (Full disclosure: This columnist is a member of the Usage Panel, and is a friend of both Stamper and Steve Kleinedler, the executive editor of the AHD.) “People who supposedly care about correct English love the Usage Panel, but for reasons that are all smoke and mirrors,” Stamper writes. “The panel didn’t have, and still doesn’t have, authority to decide which words are actually entered into the AHD.”

The people who decide what words do go into the dictionary don’t do so because they like a word, or a definition. They decide based on what people are saying or writing. People have said or written “irregardless” and “ain’t” for a long time. They may not be standard English words, but they are words. The more people use words in a certain way, the more likely that way will make it into the dictionary.

Stamper explains that lexicographers in general don’t do “real defining,” which she says is the “attempt to describe the essential nature of something.” Instead, they do “lexical defining, which is the attempt to describe how a word is used and what it is used to mean in a particular setting.” People who go to the dictionary, though, “expect to see us explain what it is.”

So the next time you run to the dictionary, think of it as councel, er, counsel on the word you are looking up. If someone is using it in a way other than one the dictionary seems to allow, don’t throw water on them just yet. You’ve always had the power to add words and meanings to dictionaries, even if you have to learn it for yourself.

RELATED: From cyberattacks to fake news: notable recent changes in AP style

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.