Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In June, a video of mob violence in northern India surfaced online. Filmed in a village near Ghaziabad, the video showed people slap and violently harass Abdul Samad Saifi, a 72-year-old man wearing traditionally Muslim clothing. The mob then cuts off his beard while he sobs. Shortly after it was posted, the video went viral and sparked widespread outrage.

Before long, several Twitter users who shared the video saw an error message indicating that their tweets had been “withheld in India in response to a legal demand.”

The legal demand was one of thousands made to Twitter directly from the Indian government over the last four years. After Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) rose to power in 2014, any online content that criticized him, the government, or Hinduism more broadly, was branded as “anti-national”—a term popularized by trolls and self-proclaimed jingoists to fuel a brash and bigoted kind of patriotism––and made vulnerable to removal.

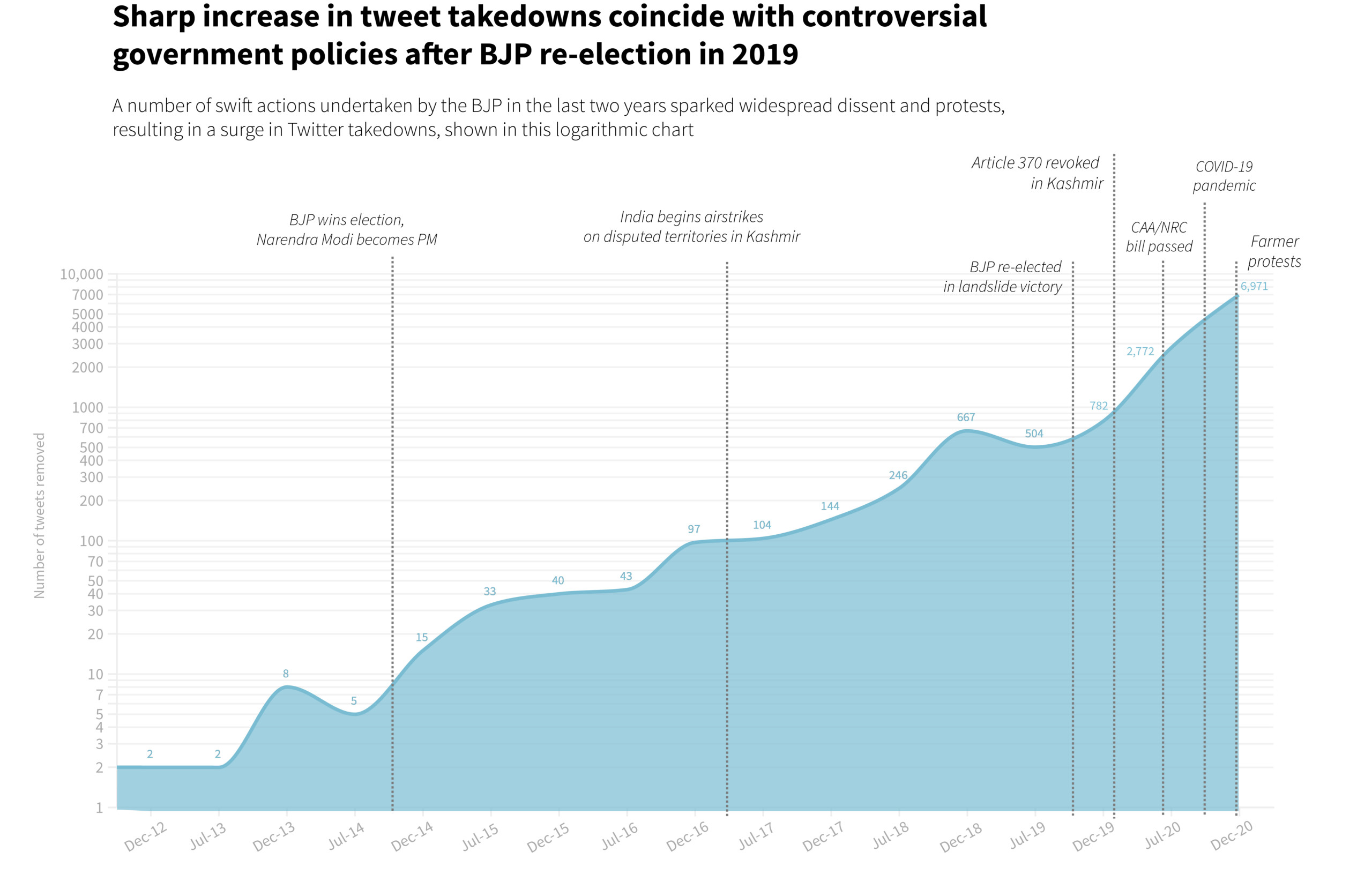

In 2020, the Indian government asked Twitter to remove nearly 10,000 tweets, up from about 1,200 the prior year; in 2017, the government only demanded that Twitter delete 248 tweets.

“There has always been a coordinated strategy to paint everyone who disagrees with the government as an enemy of the nation,” Pranav Dixit, a technology reporter for BuzzFeed News, says. “The only difference now is that Modi is far more social media-savvy than his predecessors.” Cheap internet and big telecommunications infrastructure boomed in India right around the time he took office. “Modi knew that he could sway millions of people with a single tweet,” Dixit says. “He has very deliberately and systematically built a right-wing online ecosystem that benefits his party.”

The rapid advancement of technology amplified two competing dynamics: criticism against the state became much easier, and with it, the government’s ability to control what its citizens said. And while content-removal demands by the Modi administration have come under increasing scrutiny in global media, little data exists to track the extent of censorship.

Using a combination of web scraping, APIs, and text extraction from hundreds of legal notices given to Twitter (sourced from the Lumen database, a Harvard University initiative monitoring global content removals), I created a series of datasets to better understand the nature and magnitude of the content that the Indian government wiped from Twitter. Because of a variety of factors—including the discretionary nature of Twitter’s data disclosures, the Indian government’s lack of transparency, and user-made changes to their respective flagged tweets—my data represents what is likely a fraction of the affected content. Still, these limitations provide a sense of how restrictive India’s digital climate is, and provide a narrow glimpse into a much larger problem.

Data from Twitter’s own transparency reports reveal that, in 2020, the Indian government asked Twitter to remove nearly 10,000 tweets, up from about 1,200 the prior year; in 2017, the government only demanded that Twitter delete 248 tweets.

The effects of the government’s requests for removal were only felt locally––meaning the tweets were only “withheld” if the user chose India as their country setting. In other words, even if the user was physically in India, they could change their setting to a different location and view the removed tweet. After I changed my own settings to the United States, I was able to find what most of the tweets contained. (Click to enlarge the following images.)

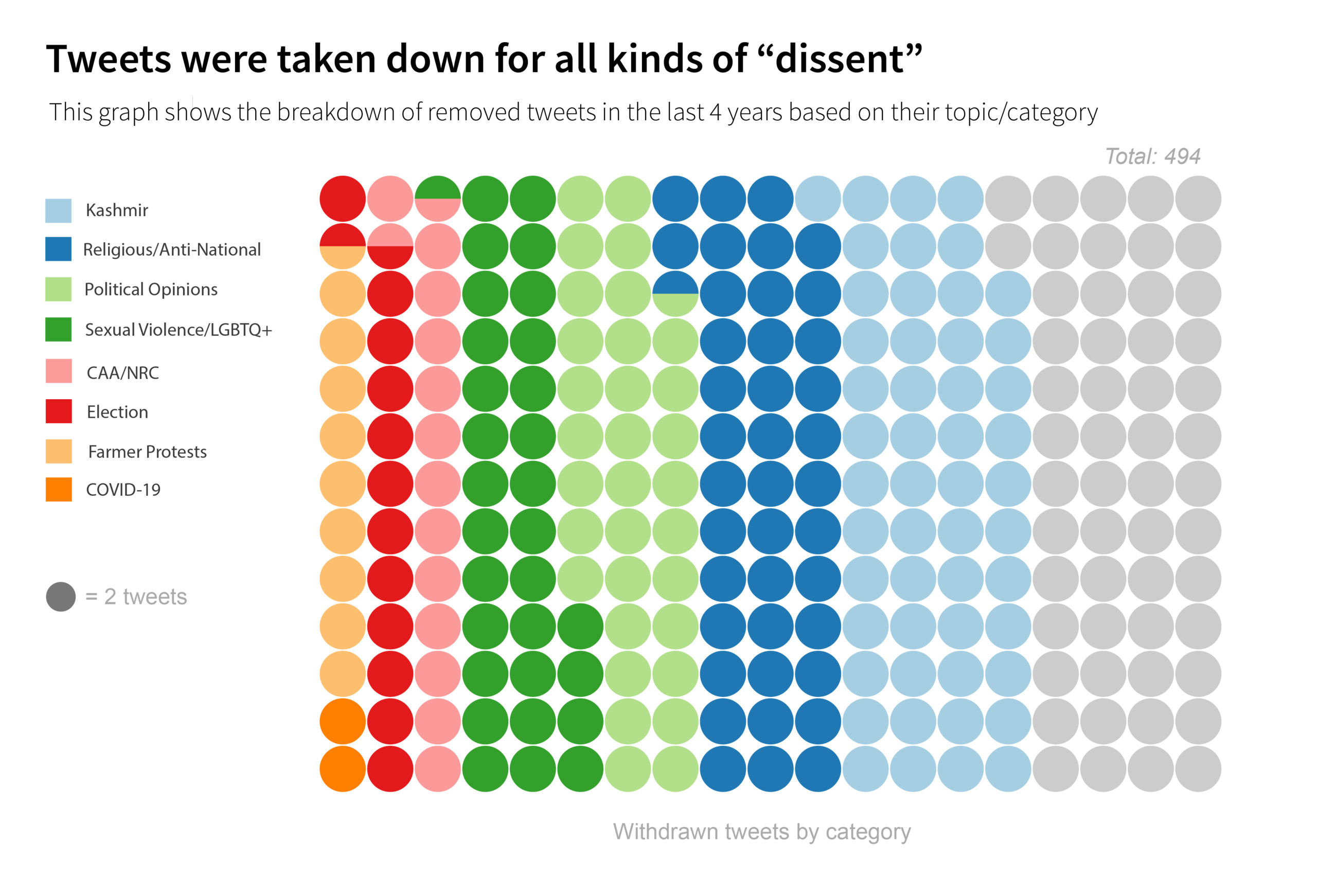

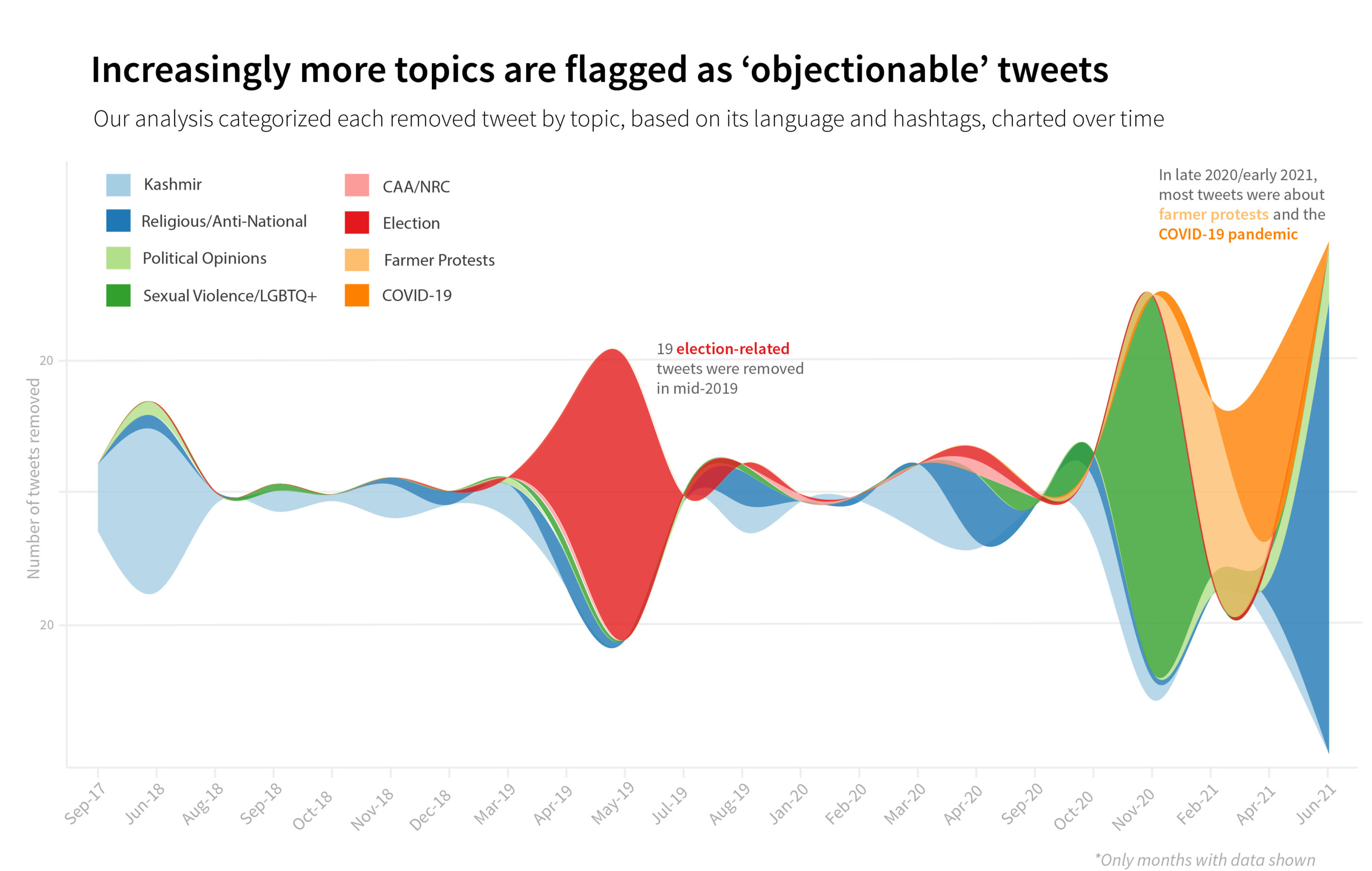

Many of the flagged tweets––which were mostly opinions on the news, satirical jokes, or expressions of solidarity with activists in memoriam––fell broadly into a few categories, and coincided with significant political or otherwise controversial events. They included criticism around the revoking of Article 370, a law that granted Kashmir its autonomy for more than seven decades since India’s independence from British rule; the passing of the Citizenship Amendment Act, which discriminated against Indian Muslims and prevented Muslim immigrants from seeking asylum; and a series of agricultural bills that sparked the largest farmer protests in the world, amidst the poorly managed COVID-19 pandemic.

The “rules” under which a tweet may be considered inflammatory are now much broader than in prior years. In the takedown notices, several tweets are cited as “objectionable” or “seditious” if they contain dissent of any kind, without further explanation. Even criticism of sexual violence—when the perpetrators were Hindu—is branded as dissent. As more tweets and topics come into the line of fire, what “anti-national” means grows murkier.

Twitter plays a complicated role in India’s political landscape. Since it’s a private company operating in India, it is legally bound to comply with national regulations. Section 69A in the Indian Penal Code allows the government to block access to a media intermediary (including TV networks, social media platforms, and search engines) “in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, its defense, security or the maintenance of public order.” When the government makes a legal demand to Twitter—which it often does without explanation—Twitter outlines how it enforces actions against reported “grievances” in reports published monthly. The rate of compliance with the Indian government’s legal demands is only around 10 percent—the ambiguously stated reason for which is that the flagged tweets may not violate Twitter’s own terms of service. (Twitter did not respond to a request for comment on more details about this internal process.)

“If Twitter takes down a random piece of content—it’s a private company, they can act according to their internal guidelines and don’t have to explain anything publicly,” Tanmay Singh, a lawyer working with the Internet Freedom Foundation. But when the government makes a demand to remove a citizen’s free speech of any kind, it has to follow due process and disclose all relevant information publicly according to India’s Code of Criminal Procedure, Singh says. The government has not made any of its court orders to Twitter publicly accessible. “What the government is doing with Twitter severely undermines transparency,” Singh says. “Without transparency, you cannot have accountability. And we absolutely need both in a participatory democracy.”

These Twitter content removals also target Indian journalists and activists. Last September, Aakar Patel, a journalist and former Amnesty International director, was arrested for posting “offensive” tweets, after which Twitter temporarily suspended his account. One tweet, made in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, was about the Black Lives Matter protests in India; another was about the history of Modi’s caste and community, a subject Patel spent years researching. (He was released shortly after on anticipatory bail.)

“Nothing I said was false or inaccurate,” Patel told CJR after his release. He added that he was not surprised by the government’s efforts to take down his tweets. “I don’t know if there are too many democracies in the world where without a police complaint, or without any sort of evidence of criminal activities, a government can force Twitter to take something down,” Patel said. “But that’s what’s happening in India.”

Before the BJP came to power in 2014, an average of three journalists were arrested per year for dissenting speech, according to the Free Speech Collective, a research and advocacy group promoting freedom of the press and the right to dissent in India. Since then, the number of journalists arrested or informally detained per year has reached an average of 14; in 2020, the number of journalists arrested or detained peaked at 51. The number of people charged with sedition––a colonial-era law still in the country’s constitution––has increased by more than a third since 2014. Most are journalists.

“I don’t know if there are too many democracies in the world where without a police complaint, or without any sort of evidence of criminal activities, a government can force Twitter to take something down. But that’s what’s happening in India.”

In September 2020, Auqib Javeed, a journalist who worked at the time for Article 14 and the Kashmir Observer, reported on the disappearance of many Twitter accounts that openly criticized the Indian state’s actions in Kashmir, during the weeks leading up to what became one of the longest internet blackouts in the region. “When so many crucial accounts suddenly went black, I wanted to know what happened,” Javeed says. “It turns out many of these users were summoned by the police, harassed, given warnings, and verbally abused. Some had to give sworn statements saying they will never say anything negative about the government again.” Javeed published his findings on 17 September 2020, under a title calling the Kashmiri police a “cyber bully.” The day after the story was published, Javeed was summoned by the police, and harassed and beaten inside a Srinagar police station for hours until he agreed to change the article’s headline. He was not formally charged with a crime.

“Journalists who have complaints against their work, get blocked, or have their content taken down are pretty much powerless against the might of social media companies,” says Geeta Seshu, founder and lead researcher on the Free Speech Collective’s Behind Bars report, which details every official and unofficial detention, arrest and complaint against journalists in the last decade. “Unless it’s a prominent figure, most people are just left high and dry–faced alone with unreported, arduous legal cases that drag on for years. We’re talking about people thrown in jail just for saying something. That’s a very dangerous breakdown of the institutions built to uphold justice.”

Methodology

First, I downloaded and compiled data from all of Twitter’s transparency reports for India, published every 6 months, beginning in January 2012 until December 2020. The final CSV file contained the total number of legal demands made to Twitter from the Indian government per time period, including the number of tweets flagged for removal and the users flagged for suspension. It also included the total number of tweets and accounts Twitter actually enforced, accompanied by the compliance rate.

To find the actual URLs and accounts flagged for removal, I scraped the Lumen database – a Harvard University initiative monitoring global content removals – using Selenium in Python, filtering for India and Twitter. Since Twitter voluntarily discloses data to Lumen, only about an eighth of the total takedown notices were available. Each notice on their database had some basic information, as well as a PDF file containing the original legal demand. After downloading the PDFs, I ran them through Adobe Acrobat’s Optical Character Recognition tool to make the scanned images into searchable text. Then I used text extraction libraries like PyPDF and PDF Plumber to pull out the unstructured text from each file, manually going through for non-English characters and other OCR glitches.

Using regular expressions, I cleaned the text and extracted all the URLs within them into a separate list. I used Twitter’s API via Tweepy to obtain information about each tweet and/or Twitter user, including the text of the tweet, the total number of tweets from that user, the bio, and number of followers. While trying to get this information, I discovered that if a user sets their country as anything other than India on Twitter––regardless of where they are actually located physically––the tweets are no longer blocked. I ran the same code twice, so both interfaces can be compared. In total, I was able to find about 500 tweets with text from the original 800 URLs that were tweets; the rest were URLs for accounts in general.

After some cleaning and formatting in Pandas, I used a combination of ScikitLearn, Numpy and a TF/IDF count vectorizer to categorize the tweets for which I had text. I chose eight categories to classify them into, based on a combination of the most frequently occurring words/sentiments, my reporting process and the general context of political events in India over the last decade. Finally, I cleaned and analyzed the data further into smaller CSV files to build a series of charts and graphics, for which I used Flourish, Altair, and Adobe Illustrator.

I also scraped Indian Kanoon, an online database for legal information, for about 1,000 PDFs containing court filings and judgments relating to Article 124A (sedition) in the hope that I could filter for cases based solely on defendants’ tweets. After rigorous cleaning and text extraction, the data proved unusable for the purpose of this story. I did, however, go through the data to identify potential sources to contact and case studies to examine further. Through my interviews, I found a report titled ‘Behind Bars’, published by the Free Speech Collective, from which I extracted data on the arrests, detentions and complaints against journalists.

All of the completed and cleaned CSV files are available on my GitHub repository, as well as the Jupyter notebooks containing the original code used to collect the data.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.