Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

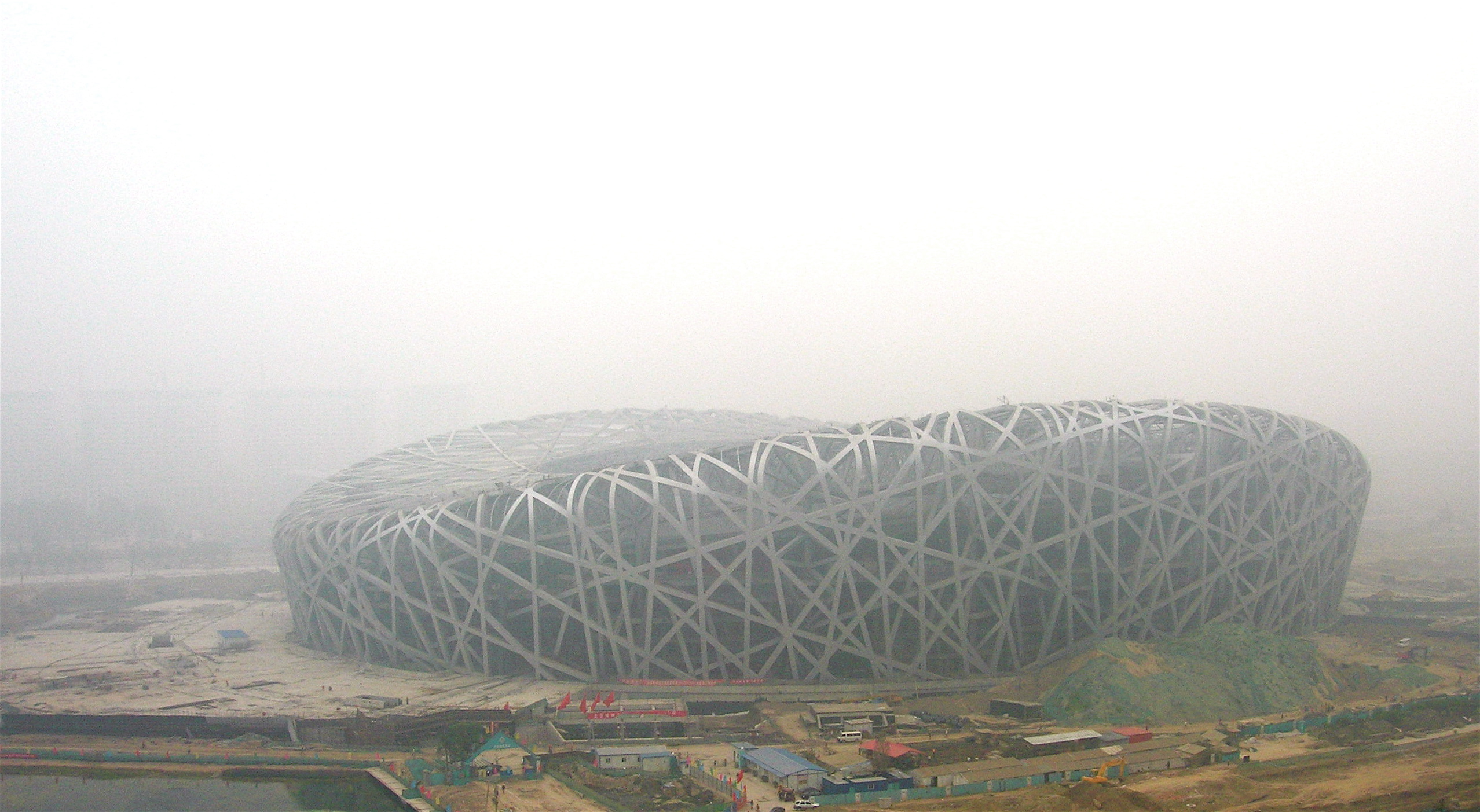

Some days the air is thick in Beijing, the sort of thick that makes you squint your eyes to double-check what’s in front of you. The air tastes to me like metal or sour eggs, maybe a mixture of both, and over a few days I can develop a phlegmatic cough. In ancient times the city was known for its fierce summer sandstorms, but in 2008, as the city prepared to host the Summer Olympics, researchers found it to be the most polluted site of the games ever. In China’s capital city, gleaming white buildings turn brown over time, and a cake of grime lines the outside of major buildings. The city is not the most polluted in the world—that honor goes to Zabol, Iran—but it’s arguably one of the most famous for its pollution.

China has made sweeping efforts to curb pollution in its most affected and populous cities in recent years. As part of its commitment to the 2016 Paris climate accord, the government has worked to decrease its dependency on coal—the leading cause of pollution in its major cities—and increase its investment in renewable energy, like wind and solar farms, with a goal of having some 20 percent of its energy come from renewables by 2030.

The day-to-day reality of smog is visible in the widespread use of smog-repellent face masks, air filters for cars and buildings, and a general practice of checking the daily smog index, like checking the weather forecast. Chinese-made phones, such as Xiaomi, Meizu, and Huawei, all offer local smog statistics on their weather apps. In addition to the temperature, citizens can check for PM2.5 (“PM” for particulate matter) levels. PM2.5 is the most harmful part of air pollution because it is small enough to travel into the lungs, causing symptoms like coughs, sore throat, and sneezing. Over time, with extended exposure to these particles, people are at risk of developing bronchitis and even lung cancer. World Health Organization guidelines suggest an annual average of 10 micrograms or fewer of PM2.5 per cubic meter as a safe level for breathing—in Beijing, the level has reached as high as 212 micrograms. Aware of the dangers, citizens now take precautions on bad smog days to limit their exposure by staying indoors when they can or by wearing special masks. Those with financial resources and access can afford air filters for their cars and homes.

But as recently as 2011, despite the thick air that people breathed in each day, many citizens had no reference point for determining what clean air is. The city government restricted any data collected about the air and pushed a narrative that the hazy atmosphere was officially fog or, at worst, mild pollution. State media outlets were forbidden to publish anything about the smog events. The city government’s story was effective: as someone who’s grown up seeing polluted days in Los Angeles and foggy days in San Francisco, I could immediately tell the difference. But I had also relied on professional weather forecasters telling me to expect a foggy—or smoggy—day. In Beijing, when I took taxis, entered restaurants, and chatted with people casually while waiting for the bus, they commented on the fog rather than the smog.

The city government restricted any data collected about the air and pushed a narrative that the hazy atmosphere was officially fog or, at worst, mild pollution.

The fog-smog narrative is a classic form of disinformation driven, in this case, by a state actor. Disinformation campaigns have existed since time immemorial; they are a way to sweep away inconvenient truths and construct in their place an alternative “truth.” What happened in China between 2009, when pollution started becoming too serious to write off as sandstorms or fog, and 2014, when the government released its first official decree against pollution, sparking a nationwide push for clean air and clean water? In part, citizens began using the internet, and in particular, memes, to evade censorship.

In 2008, the US Embassy in China started a Twitter account called Beijing Air (@beijingair). It had a simple goal: publish data about the air in the city, collected directly from the embassy grounds. The embassy was technically on US soil, and therefore its staff could safely collect and disseminate the data. But the impact was limited: with Twitter being blocked and the data communicated primarily in English, the site largely reached a Western audience and only a limited Chinese one. Even when a site like Twitter is blocked in China, it’s not impossible to tap into it. Many foreigners, accustomed to accessing popular social networks—Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube—find an entry point through a VPN, or virtual private network, which creates a simple way to encrypt data from blocked sites and allow it to tunnel through the block. Chinese citizens can do the same, but costs can be prohibitive.

By 2011, antipollution advocates in China had a new tool at their disposal: the iTunes App Store. At the time, iPhones were financially out of reach to most Chinese consumers, and censorship was not applied extensively to what apps were made available on the App Store. A few activists developed apps, like DirtyBeijing, that took data from the Beijing Air feed and visualized that in clear and simple language. These apps contained a simple feature: take a screenshot and share it to Sina Weibo. And share people did. They began posting the photos of the day, explaining what PM2.5 was, and using the data, they could state whether the air in, say, Beijing was dangerous.

At the same time, another meme emerged on the Chinese internet. People simply began posting photos of the air around them. Some people posted from high-rises, others from down on the ground looking up into the sun. Others posted pictures of themselves wearing masks, and others the walls of their buildings, which showed clear signs of pollution. This collective action helped establish clear patterns of pollution across the country and within different cities, making clear that air pollution wasn’t an isolated incident on a given day, nor that only one person questioned the idea that the haziness was fog.

A number of activists also distributed low-cost air sensors. According to Ellery Biddle, editor of Advocacy Voices, the sensors played an important role in helping people collect data for themselves. Because these sensors were do-it-yourself, people could not only collect the data but could also talk about it with friends and share it online. Projects like artist Xiaowei Wang’s Float Beijing used kites with sensors that would collect data in the skies and drew on a long kite-flying tradition in China. Another project, Clarity, was a keychain-sized sensor that collected data in a highly distributed fashion.

During this time, filmmaker and journalist Chai Jing released online Under the Dome, a groundbreaking documentary about air pollution in the country. Running at more than an hour, it went viral, with 150 million views on Chinese social media. In the film, Chai talks about how she became pregnant and learned that her child had a tumor: “I’d never felt afraid of pollution before, and never wore a mask no matter where. But when you carry a life in you, what she breathes, eats and drinks are all your responsibility, and then you feel the fear.”

China’s environmental minister praised the documentary for its honesty and impact, but the film was censored after a few days. Even then it was too late. Meme culture depends on the strength of people’s video-editing skills, and they were able to cut and paste images and clips, disseminating short bits of video and memes or share the entire video file directly. People started conversations online about pollution.

Over time, international pressure grew as Western journalists also began writing about the pollution situation. Journalist Mark MacKinnon, in the Globe and Mail, captured the sentiment of many journalists at the time who were living and writing in Beijing and other polluted Chinese cities. The US embassy’s assertions, he wrote, “that the air usually wobbled between ‘unhealthy,’ ‘very unhealthy’ and ‘hazardous,’” was “being seized upon by anxious Chinese Internet users and even some domestic media outlets as proof that air pollution was far worse than their government was telling them.” Yet, MacKinnon continued, state-run media said the pollution in Beijing the day he was writing was “moderate” and urged people to “open the windows and inhale the fresh autumn air.”

Even though the Chinese government seeks to influence international journalists living in the country, they can’t fully control the narratives being produced. Sina Weibo gave journalists abroad an opportunity via social media to see the growing conversation. For example, the site Tea Leaf Nation covered online phenomena like China Air Daily, an online publication that would collate citizens’ documentation of air pollution around the country. These in turn created a pipeline of articles about pollution and Chinese citizens’ growing discontent and sparked further action from middle-class Chinese, who are more likely to travel (and therefore see what blue skies look like) and have greater economic and political muscle within the country.

Memes always exist in a broader media environment, and political memes take their strength from this fact. Different types of media have different audiences and impacts, and internet memes play one role in the bigger picture. While people posted photos, selfies, and GIFs to discuss the impacts of pollution on their lives, the number of news articles, broadcasts, documentaries, and international conversations increased. “The most effective use of social media for social transformation occurs,” MIT professor Sasha Costanza-Chock writes in Out of the Shadows, Into the Streets!, “when it is coordinated with print and broadcast strategies, as well as with real-world actions.” Specific to the situation in China, Biddle emphasized that overcoming the misinformation about pollution was a “distributed project,” where multiple people took data, shared feelings and photos, and generally had a chance to connect dots. There was no one message, no one form of media, no one person who effected the change in the face of tremendous disinformation efforts—the multiplicity was critical.

There was no one message, no one form of media, no one person who effected the change in the face of tremendous disinformation efforts.

As pressure mounted, the Chinese national government made a pledge to respond. In 2012, Beijing’s environmental agency began placing PM2.5 measurements in its calculations and set monitoring standards across dozens of cities. The standards they set allowed them to say that they were taking action and to direct public pressure to other organizations as needed. It also improved their appearance in the international community, thus helping improve their foreign policy aims and continuing their efforts to attract tourists (and tourist dollars). What was the effect? Over time, the narrative about the air shifted from “fog” to “smog,” eased along by open data initiatives, memes, and media that aimed to surface the truth about air quality.

In China, in a matter of a few years, a remarkable new culture has emerged. Information is still restricted and the root issues still unaddressed and the national government continues to try to restrict alternative sources of information, pushing only official statistics and even insisting at times that fog is still the core issue and detaining people for “rumor mongering” about particularly bad air. But citizens now wear masks, check the air quality, make efforts to advocate for clean air and water (within certain limits), and see their doctor. Today, Chinese-made phones feature pollution data on their interfaces. Baked into the weather app, they forecast the temperature, whether it will rain or snow, and whether you should wear an air mask or plan to stay indoors. Air filters are sold openly in markets in Beijing for both cars and homes, and people regularly post selfies wearing air masks. When Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg posted a picture of himself taking a friendly jog in Beijing, Chinese netizens poked fun at his thinking that jogging would be a good idea, especially without a mask on.

What’s remarkable is how, in a country where trust in institutions is low but censorship and misinformation are high, a critical mass of people recognized that they were being tricked by government data about pollution. To me, it’s not coincidental that this particular form of memetic advocacy involved something we can see before our eyes as well as the distribution of physical sensors and independent data. In an authoritarian environment, this can create unique opportunities for change, even within a limited scope, as people find roundabout ways to make space for conversation despite government opposition. You can deny an image online or a statistic as false, but seeing people with your own eyes showing up for something they believe in is much more difficult to turn away.

Memes to Movements: How the World’s Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power is now available from Beacon Press.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.