Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

“There are three ways to deal with propaganda—first, to suppress it; second, to try to answer it by counterpropaganda; third, to analyze it,” the journalist turned educator Clyde R. Miller said in a public lecture at Town Hall in New York in 1939. At that time, faced with the global rise of fascist regimes who were beaming propaganda across the world, as well as US demagogues spouting rhetoric against the government and world Jewry, the rise of Stalinism, and the beginning of the Red-baiting that foreshadowed McCarthyism, scholars and journalists were struggling to understand how people could fall for lies and overblown rhetoric.

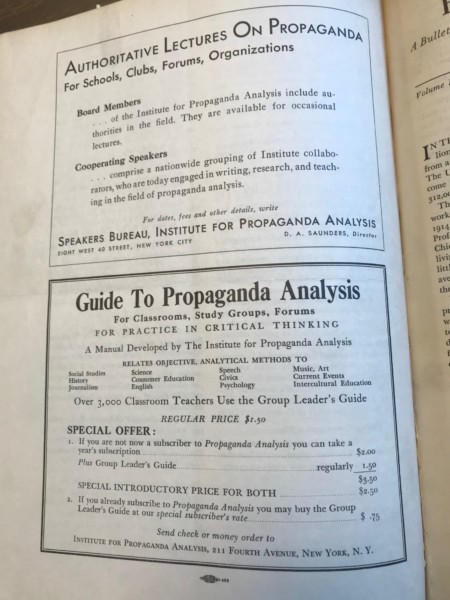

In response to this growing problem, Miller, who had been a reporter for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, founded the Institute for Propaganda Analysis in 1937. To get the institute up and running, Miller got a $10,000 grant from the department store magnate Edward A. Filene, who had by then begun making a name for himself as a liberal philanthropist. Based at Columbia University’s Teachers College, with a staff of seven people, the IPA devoted its efforts to analyzing propaganda and misinformation in the news, publishing newsletters, and educating schoolchildren to be more tolerant of racial, religious, and ethnic differences.

In order to understand what kind of people, under certain circumstances would be susceptible to fascism, some sociologists studied personality traits. While it was clear that Germany’s defeat in World War I and subsequent economic conditions there, including widespread unemployment, had paved the way for the rise of Adolf Hitler, academics and journalists tried to parse just what made Nazi propaganda so effective at galvanizing public support for the regime. Theodor Adorno produced his famous “F-scale” (the “F” stands for fascist), which aimed to identify individuals more susceptible to the persuasions of authoritarianism. In recent years, the research of behavioral economist Karen Stenner has similarly examined the ways that innate personality traits coupled with changing social forces can push some segments of society toward intolerance.)

For its part, the IPA, under Miller’s leadership, maintained that education was the American way of dealing with disinformation. “Suppression of propaganda is contrary to democratic principles, specifically contrary to the provisions of the United States Constitution,” Miller said in his 1939 speech. “Counterpropaganda is legitimate but often intensifies cleavages. Analysis of propaganda, on the other hand, cannot hurt propaganda for a cause that we consider ‘good.’” In other words, analyzing propaganda for a good cause would not undermine the cause itself—but analysis of “bad” propaganda would allow audiences to dismantle its effects.

In the 80 years since Clyde Miller first set out to tackle this problem, the dissemination of propaganda in our society has become only more sophisticated and perhaps more ubiquitous. The recent rise of Facebook and Twitter, along with the capabilities they offer to micro-target specific particular audience demographics, and the ongoing controversies of the 2016 election—among them the prospect that ideologically motivated foreign actors used social media to disseminate false information—have brought a renewed flurry of interest in the kind of propaganda, misinformation, and disinformation that pervaded the country nearly a century ago. So it’s not surprising that we again see growing interest in developing techniques for identifying and unraveling them.

Foundations including Hewlett Foundation, Ford Foundation, Open Society Foundation, and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, have begun slow and expensive efforts to educate people to think critically, build trust in media outlets, analyze disinformation, and fight propaganda. Governments around the world, including in Germany, Malaysia and the European Union, are starting to regulate social-media platforms, as evidenced by recent efforts by European governments to require Facebook and Twitter to crack down on illegal hate speech. But social media platforms have largely taken the stance that the onus is on the audience to figure out what is fake and what is not. Meanwhile, they tweak their algorithms, mount an array of technical fixes, and employ human moderators to block inflammatory content.

In light of all this, it’s worth looking back to one of the earliest attempts to tackle this age-old problem. What, if anything, can we learn from the efforts of the IPA in the 1930s? And why are we again falling prey to the kinds of disinformation campaigns that it aimed to inoculate society against?

In her Group Leaders Guide to Propaganda Analysis, the IPA’s educational director, Violet Edwards, argued that industrialization and urbanization made society bigger and more complicated and so the “common man” had become “tragically confused” by an overload of secondhand information and the need to make decisions about subjects without having firsthand information.

Instead of the town hall or the cracker barrel of yore, where citizens could meet to discuss the topics that affected them personally, Edwards wrote, they now had to rely on information from others about how society should be organized and which policies should be pursued far from home. Meanwhile, many others, including the American writer Walter Lippmann and the French philosopher Jacques Ellul, had begun arguing that journalism could become a means to sift through and distill the excessive information now available to the masses in part because of increasing newspaper circulation and radio broadcasts.

To properly understand the secondhand information on which citizens depend, Edwards wrote, readers should adopt a scientific mindset of fact-finding and logical reasoning and think critically when confronted with secondhand information. The IPA developed techniques for analyzing information that would help audiences think rationally. They brought media literacy training into US schools in an attempt to inoculate young people from the contagion of propaganda by teaching them how to thoughtfully analyze what they read and heard. (Again, something that is being tried today.)

Miller categorized propaganda into seven types. These included “glittering generalities,” “name calling,” “testimonials,” and “transfer,” a means by which “the propagandist carries over the authority, sanction, and prestige of something we respect and revere to something he would have us accept.” Using another tactic, “Plain Folks,” Miller argued, propagandists “win our confidence by appearing to be people like ourselves,” while “bandwagon” was a “device to make us follow the crowd to accept the propagandists’ program en masse.”

Soon after the founding of the IPA, Miller was praised for bringing “the newspaper man’s passion for simplifying complicated subjects”: Among the IPA’s regular output, were analyses of political speeches, with little icons—the emoji of the day—printed next to each phrase to explain which of these techniques the speaker was using. One such book analyzed the anti-Semitic radio broadcasts of the infamous Father Coughlin, a Catholic priest in Detroit who was estimated to draw 30 million listeners for his attacks on the international Jewish population and President Roosevelt, among other topics.

Miller also published something he called the “ABCs of Propaganda Analysis,” which exhorted readers to first concern themselves with propaganda, then figure out the agenda of the propagandist, view the propaganda with doubt and skepticism, evaluate one’s reactions to it, and finally seek out the facts. He hoped audiences would use the ABCs to become active readers who could carefully analyze their reactions to propaganda.

Additionally, Miller published a weekly Bulletin that described an important topic in the news, analyzed the propaganda techniques used by all sides, and included a detailed list of sources he’d used and recommended further reading and discussion questions. This struck a nerve: Some 10,000 people subscribed to the Bulletin, which cost $2.00 a year (about $32.00 in today’s terms), and 18,000 people bought the bound volume of back issues that was published at the end of each year.

Here’s a sample analysis of the fake news of the day, taken from the May 26, 1941, issue of the Bulletin:

Persistently since the influx of refugees from the war areas began, a story has bobbed up in numerous American cities about the alleged heartless—and actually unreal—discharging of regular employes [sic] by stores to make places for ‘foreigners’. The story usually is anti-Semitic; the store with which it is connected has Jewish owners, and Jews are said to get the jobs.

One large store in New York City which has been a victim of the story has spent considerable sums trying to trace the source and find some way of stopping it. The efforts have been fruitless. The story keeps reappearing, and mimeographed leaflets have even been circulated picturing the Jewish manager welcoming a long line of Jewish refugees while turning away another line of fine Nordic types.

As part of the IPA’s attempts to spread its message and techniques, the organization sought to put young students on guard against propaganda and to form them into sophisticated news consumers. The institute formed a relationship with Scholastic magazine, and in 1939 and 1940 produced a series that was distributed in schools, called “What Makes You Think So?; Expert Guidance to Help You Think Clearly and Detect Propaganda in Any Form.” By the late 1930s, 1 million school children were using IPA’s methods to analyze propaganda, and the IPA corresponded with some 2,500 teachers. Anticipating contemporary critiques, such as the argument by danah boyd, founder of the technology-analysis organization Data & Society, that media-literacy programs can cause audiences to become dangerously mistrustful, the IPA maintained, in its teaching guides, that students needed to think critically as part of being engaged citizens:

The teacher who acts as a guide to maturity helps her pupils to think critically and to act intelligently on the everyday problems they are meeting…. [B]y its very nature [the] process will not build attitudes of cynicism and defeatism.

The IPA also helped design curriculum aimed at promoting civic engagement and racial and religious tolerance that was piloted in the Springfield, Massachusetts, school district, whose superintendent was sympathetic to the IPA’s mission. The “Springfield Plan” was influential and replicated in other districts but petered out in Springfield itself after a few years partly due to criticism by the Catholic Church and lack of local support as religious tensions rose locally after World War II. By the early ’50s, as McCarthyism was taking hold, there were murmurings that the plan contained “subversive” elements.

Miller spent 10 years at Columbia Teachers College as Communications Director and as an associate professor. In that time, IPA used up $1 million of Filene’s money. It was World War II that caused the end of the IPA, in part because the US began producing its own propaganda to galvanize support for the fight against Hitler. Publication of the weekly Bulletin ceased in 1942, as the US entered the war. In its farewell issue of January 9, 1942, headlined “We Say Au Revoir,” the IPA explained that its board of directors had voted to suspend operations:

The publication of its dispassionate analysis of all kinds of propaganda, ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ is easily misunderstood during a war emergency, and more important, the analyses could be misused for undesirable purposes by persons opposing the government’s efforts.

This final Bulletin expressed satisfaction with the work achieved by the IPA, warned that wartime is usually accompanied by a rise in intolerance, and expressed the hope that IPA techniques for analyzing propaganda would be used in the future, which indeed they were.

Miller’s time at Teachers College came to a sad end, as he apparently fell victim to the very intolerance he had warned against. Along with some other faculty members, he was put on leave from the college in 1944, amid a financial crisis at the institution, and he never resumed work there. In 1948 Miller was officially let go. Miller was told his dismissal was the result of departmental restructuring—but William Randolph Hearst’s animosity towards Miller may have contributed. Hearst was known for attacking “Reds” in the universities and schools and his paper, The World Telegram, had criticized some of the educational activities Miller was involved with. Hearst had complained to Teacher’s College about Miller, saying he should “lay off.” The House Unamerican Activities Committee in 1947 also attacked the IPA calling it a “Communist front organization.” The late 1940s were a prelude to the McCarthy years of the 1950s and HUAC had begun going after members of the American left. As far as we know, Miller was not a Communist or a “Fellow Traveler” but his involvement with IPA, the Methodist Church and the Springfield plan was enough to cause Hearst’s papers to smear him. There were a lot of gray areas during the McCarthy era blacklists. Some professors were fired by their Universities while others were let go quietly. Miller may have been one of these.

Miller lost his Columbia housing and salary and wrote repeatedly to Columbia’s president decrying the “violation of tenure and academic freedom.” He also told the New York Tribune, “I can understand that during the depression and now in this period of post-war hysteria, academic freedom is a pretty hard thing to preserve.” For a while Miller worked at The League for Fair Play, which was based in New York and helped publicize the Springfield Plan. But then the trail goes cold. On a trip to Australia in 1999, Miller died; he’s buried there.

Yet Miller’s legacy lives on. Although it was phased out in Springfield, the ideas of his education plan continued. According to Boston College education professor Lauri Johnson, “the Springfield Plan became the most well-publicized intercultural educational curriculum in the 1940s, talked about and emulated by school districts across the country and into Canada.”

And after the dust from WWII had settled, researchers, led by Yale’s Carl Hovland, once again took up the discussion of media effects and propaganda. Rather than focusing on specific propaganda techniques, Hovland took a broader view, attempting to understand how the media garnered credibility. Among other topics, Hovland and his group of scholars tried to understand if the source of a message affects whether people trust it, whether the content of the message matters or (as with Adorno’s F-scale) if audience characteristics are the most important. Hovland believed that highly intelligent people may be more able to absorb new information but are also more skeptical. People with low self-esteem who “manifested social inadequacy…showed the greatest opinion change.” However, despite extensive studies as to what caused media persuasion, Hovland’s findings were inconclusive. Scholars still grapple with the questions he tried to answer.

Additionally, many of the techniques the IPA pioneered are still used today in media-literacy training classes in US schools. Many take as their foundation the IPA’s pioneering ideas about how best to understand and combat propaganda, including a belief in the need for personal reflection and for understanding how personal experience shapes one’s ideas.

In fact, it’s striking how closely the IPA’s discussions about disinformation and possible remedies to it resemble the conversation we’re having on this topic today. For instance, researchers such as Claire Wardle, the executive director of First Draft, a think tank at Harvard’s Kennedy School that aims to fight disinformation, along with various others, have called out the techniques used by people spreading propaganda, and delineated taxonomies of the different kinds in use.

It would be nice to think that the IPA’s efforts worked and a generation of children became inured to propaganda and disinformation. In fact, the rise of Nazism in Germany happened in part because of the effectiveness of German propaganda and the US also went down the road of McCarthyism and anti-Communist propaganda. Moreover, it turns out that it’s devilishly hard to prove that media literacy is very effective. New research by University of Pennsylvania Annenberg Professor Kathleen Hall Jamieson suggests that the Russian disinformation campaign on social media may have worked because it reinforced the points made by Trump in his campaign. Moreover, people who believe in fake news keep believing it even when confronted with information.

The lesson of the IPA is not just that media literacy education is hard to do well but that when societies become truly polarized, just teaching tolerance and critical thinking can be controversial. In the 1940s Clyde Miller was attacked for his efforts. In today’s polarized world it’s not hard to imagine a similar backlash.

Author’s Note: Thanks to Chloe Oldham for her research, Andrea Gurwitt for her editing, and Professors Andie Tucher, Richard John, and Michael Schudson for their comments. Thanks to Thai Jones and the librarians working with the archives at the New York Public Library, Nicholas M. Butler Papers and the Columbia University Archives Central Files.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.