Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

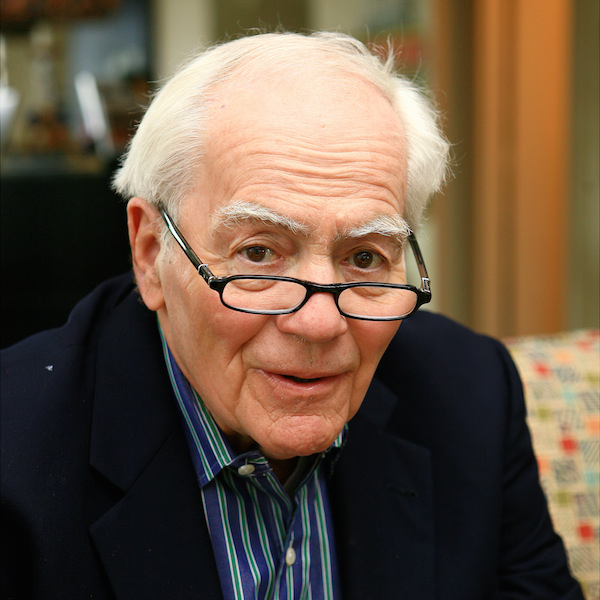

With the passing of Jimmy Breslin on Sunday, we’re republishing a couple of pieces that we wrote about the legendary columnist over the years. Breslin’s wit and rage were constant companions for those who plucked copies of The New York Herald Tribune, The New York Daily News, or Newsday from their driveways or corner stores during his various stints at each paper. In an interview with The New York Times, Breslin explained that his approach went back to his days covering sports: “Don’t go where the others go. Go to the losers’ dressing room at all times.”

The first story below comes from the November/December 2001 issue, CJR’s 40th anniversary, in which we picked one journalist who best represented each year in the publication’s history. Scott Sherman briefly tells the tale of how Breslin found himself at the center of a manhunt for the infamous “Son of Sam” serial killer.

In the second piece, published in the January/February 1989 issue of CJR, Mike Hoyt celebrates the 80s tabloid wars sparked by Breslin’s move from the New York Daily News to New York Newsday.

Jimmy Breslin: The Killer Was a Reader

It was the summer of 1977 in New York, and madness and hysteria were in the air. The temperature hit 104 degrees, the city was broke, Puerto Rican nationalists set off bombs in midtown Manhattan and a blackout led to widespread looting. On top of it all, a madman—David Berkowitz, a.k.a. “Son of Sam”—was stalking the streets, killing people with a .44-caliber pistol. In a bizarre twist, Berkowitz contacted the city’s preeminent newspaper columnist, Jimmy Breslin of the New York Daily News. “Hello from the gutters of N.Y.C. which are filled with dog manure, vomit, stale wine, urine and blood,” Berkowitz wrote in a letter to Breslin in June 1977. “Hello from the sewers of N.Y.C. which swallow up these delicacies when they are washed away by the sweeper trucks. Hello from the cracks in the sidewalks of N.Y.C. and from the ants that dwell in these cracks….” Berkowitz was nothing less than a fan: “J.B.,” he affirmed, “I also want to tell you that I read your column daily and find it quite informative.”

In 1977, Jimmy Breslin was at the top of his game. Along with Chicago’s Mike Royko and San Francisco’s Herb Caen, Breslin, first in the New York Herald Tribune and later the New York Daily News, personified the big-city columnist. Breslin turned out gritty, intimate columns, bursting with staccato prose and human voices and Irish melancholy. In person, he was a tangle of contradictions: playful, blustery, vainglorious, always ready with an insult. Given his celebrity status, it wasn’t entirely surprising that Breslin himself became a dramatic character in the “Son of Sam” case: In the same column in which he printed excerpts from the Berkowitz letter, Breslin pleaded: “The only way for the killer to leave this special torment is to give himself up to me, if he trusts me, or to the police.”

Berkowitz was eventually captured, but he never got Jimmy Breslin off his mind. “I heard from him a couple of years ago,” Breslin wrote in 1993. “He sent me a Christmas card from Attica. He had a drawing of the Devil on it. He wrote that he wished me a Merry Christmas from the Devil. He signed it David Berkowitz.” Breslin remains a New York fixture: He had a starring role in Spike Lee’s film Summer of Sam, and he continues to turn out gritty, melancholy columns from the city for the mostly suburban readers of Newsday.

–Scott Sherman

Jimmy Breslin and the New York tabloid wars

In late summer and early fall people watching television around New York City began to see a puzzling series of ten-second ads that featured various parts of someone’s body and an urgent, bad-poetry voice-over: These are the eyes/sharp and keen/that well remember/all they’ve seen—this over a pair of screen-filling and slightly blood-shot peepers. These are the fingers/often heard/that pound the keys/that tap out the words—this over some rapid one-finger-method typing on a portable computer, somehow made to clack like an old Royal. These are the fists/hard and tough—this over these same hands, now clenching and slamming into each other’s palms. The hands actually seemed kind of pudgy and benign.

These were the hands, eyes, feet (That pound the street, etc.) of Jimmy Breslin, the heavyweight champion of the New York newspaper columnists. Not only had New York Newsday snatched Breslin away from the New York Daily News, but it had snatched the News’s advertising agency, Holland & Calloway, as well, and these two prizes had joined forces to beat up on their old employer. In September the ad campaign would change to a “Breslin switched—How about you?” theme, but the earlier teasers never mentioned the columnist’s name. They all ended with some breathless variation of “He’s coming! September 11! Only in New York Newsday!”

On September 11, when Breslin finally did arrive, Mike McAlary and Bob Herbert of the Daily News were waiting for him like a pair of muggers hiding around the corner. McAlary, a former investigative reporter hired away from Newsday a short while earlier, and Herbert, a former News city editor, were part of the News‘s “new generation” of columnists. The News‘s current TV campaign shows them in such journalistic activities as putting on trench coats on the run and dialing pay telephones in the rain. Breslin is the champ, so the News double-teamed him.

Who won? New York City won.

In McAlary’s page-two column we got the story of Nicholas Longo on the night he and the majority on the Yonkers city council were caving in to fines that were crippling that city, just north of the Bronx, and finally agreeing to a court ordered plan to build low-income housing in middle-class white neighborhoods. The fines, doubling every day, would soon have meant municipal layoffs. McAlary depicts Longo reading the names of the city employees who would be the first to go, including Rosemary Doerr, who does most of his secretarial work. Then Longo casts a “yes” vote for the housing plan. McAlary quotes a voice in the crowd: “You snake. We won’t forget.”

That same day, Herbert wrote an excellent column about Darryl King, who has spent the last seventeen years in prison for the killing of an off-duty rookie cop named Miguel Sirvent during a holdup. Herbert introduces us to a lawyer and a private investigator, an ex-cop named Bo Dietl, who have taken up King’s cause and who lay out a convincing array of evidence that he’s an innocent man. “If he had killed a cop, I’d put him in the electric chair myself and personally pull the switch,” Dietl tells Herbert. “But he didn’t do it.”

And over in Breslin’s roomy corner, on page two of New York Newsday, we visit the ninth-floor nursery for long term baby care at a big hospital in a poor area of Brooklyn. This is a place for infants damaged by AIDS or drugs, and Breslin shows us a rangy male nurse named James Rempel holding an odd-acting child in a blue sweater. Rempel tells us that because the baby’s mother smoked so much crack, the baby is mad. We get a column of power and sorrow, putting a human face on the headlines.

It can’t, I suppose, but I hope this New York newspaper war goes on and on.

People raised Catholic are always a little vulnerable to calls for penance and purity. When I was in college, the people I shared a house with somehow convinced me to join them in a new diet which, for the first week, consisted of nothing but brown rice—morning, noon, night. This macrobiotic fad actually killed a few people around the country, but in our case we broke down after three or four days and hastened to a highway diner for a wonderful breakfast of steak and eggs.

In a similar brown-rice sort of vein I changed my news-intake regimen a couple of years ago: no tabloids, more MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour. This fall I could stand it no longer. Maybe it was the presidential campaign: one more bloodless set of spin doctors playing tennis with the issues. Gimme red meat, I thought, and quietly purchased 95 cents worth of New York tabloids.

And what a feast. Back when I had quit them, the Daily News was exhausted, the Post a joke, and New York Newsday too new to notice. Now everything had changed.

Just about everyone I’ve talked to about this agrees that the level of tabloid journalism in New York has been steadily rising. Most of them cite two main factors: the departure of the Post’s Rupert Murdoch and the arrival of Long Island Newsday’s offspring, New York Newsday. “There was a period where there was a kind of Gresham’s law operating,” says Michael Oreskes, a New York Times reporter who was once city hall bureau chief for the News. “I blame the Post mostly. The bad was driving out the good. Everybody was being pulled down.”

Because he owns a New York television station, Murdoch was obliged under cross-ownership rules to sell either the station or the Post; real estate developer Peter S. Kalikow bought the paper in March 1987, and it has been toning down its Fleet Street style since then. When a deranged and unclothed man killed an usher in Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in late September, the Post was the only New York tabloid not to get the word “naked” onto page one. Alexander Hamilton, who founded the paper in 1801, now makes an appearance in the upper left-hand corner of that page, and a recent Post ad tells him not to worry, that his paper is in good hands.

Editorially it is in the hands of Jane Amsterdam, who was hired and promised autonomy last May. Amsterdam is new to newspapers; she has been known as a gifted magazine editor since her days at New Jersey Monthly, where the Jason R. Golden on the masthead turned out to be her pet retriever. The Post has improved its real estate section and hired a solid third columnist, veteran Pete Hamill. Murdoch raised circulation to nearly 1 million at one point (it’s about 600,000 now) but never could attract enough advertising to stop bleeding money. Hamill thinks one of his mistakes was to make the Post “so simple minded that it never got home; you consume it in fourteen minutes on the subway and it ends up in the trash can”—a location advertisers resist. That consumption time may be up a few minutes now, but the Post is still the thinnest of the three. It will add some substance on March 5 when it launches a Sunday paper, a $25 million investment that Kalikow promises will include “more feature stories, [more] investigative and in depth reporting.” “In a year or so you won’t recognize the Post,” Hamill says. But for now the newspaper seems to be between personalities.

This is not the case with the Daily News, the streetwise tough guy, the admirer of hero firemen. In News headlines, Jesse Jackson is JAX; John Cardinal O’Connor is O’C. The third largest newspaper in the country has never been burdened with excess subtlety. When former Bronx political boss Stanley Friedman was convicted a second time on corruption charges in late October, a News editorial concluded that he was “scum that rose to the top of the cesspool and, thank the Lord, was scraped off.” A speculative story on what a George Bush cabinet would look like quoted a friend of Bush on the possibility of Maureen Reagan becoming United Nations ambassador: “If he picked Quayle he could pick that jarhead.” You don’t get this kind of perspective in The New York Times.

Like the Times, New York Newsday has a more genteel, suburban personality than the News. Newsday offers a lot more international coverage—the Daily News concentrates nearly all of its energy on the city—and a fatter life-style and features section. Newsday’s innovative editorial pages are almost always more interesting than those of its rivals, and it’s the only city paper that offers color photos on page one.

Over at the News you can pick up mutterings that Newsday is not really a tabloid. “It’s really a broadsheet sort of newspaper,” says News columnist Bob Herbert. “Part of the idea of a tabloid is to be sharp and snappy.” “Look at their garbage thing,” sniffs a News editor, referring to a ten-part Newsday series on solid waste that ran last winter. “It’s an incredibly extensive series that I’m sure nobody read.” But most competitors are more generous. “New York Newsday has shown that you could be a tabloid and still be good, that you don’t have to be The Christian Science Monitor,” says Pete Hamill, who calls tabloid journalism “the first draft of social history.”

“Newsday,” says Daily News columnist Juan Gonzalez, “has put a whole new factor into the equation.” instead of “Zingo”—the circulation-building game the News came up with in a fit of creativity after Murdoch’s Post invented “Wingo” a few years back—New York tabloid competition now seems to be about “going after people who care about the city and who want real news,” says Tom Robbins, an investigative reporter recently hired by the Daily News from the The Village Voice. Newsday puts a fair amount of emphasis on the sort of issues that tabloids are not famous for covering, such as housing and education, and it is making steady progress. Back when the paper’s circulation was around 120,000, News editor Gil Spencer was reported to have said that he lost that many papers off his trucks each day; if that’s the case now that Newsday is around 175,000, he might check the fleet’s shock absorbers.

In recent months, Newsday specials have included a scary four-part series on the bootleg weapons trade in New York, a three-part investigation into the city’s chaotic and outmoded elections system, and a fourteen-part look at the “Trials & Triumphs” of blacks in New York.

But the Daily News has been energetic too, breaking the Wedtech corruption scandal, which has resulted in the conviction of one New York congressman and the indictment of another, and investigating allegations that state comptroller Edward Regan had been trading state business for campaign contributions. The paper ran an excellent four-part series on the Holland welfare hotel, describing it as a place where the poor live in misery, drug dealers thrive, and the owners milk the city.

Newsday’s competition is not the only change in chemistry at the News, which for a while seemed likely to be crushed to death between its owner, the Chicago based Tribune Company, and its unions, but which emerged from the ordeal in fighting shape. “We were already moving in the area of more projects, more emphasis on life in the city,” says Arthur Browne, metro editor at the News. “We were saying, ‘Let’s get away just a little bit from running for every crime, every fire, every ambulance siren.’ Then Newsday came along with this reputation as a very thinky paper, and you look at them and say, ‘What lessons are to be learned from this?’ There is no question in my mind that the level of journalism in New York City has risen, and that there are more interesting voices in the city than there were.”

More interesting voices. Here is Gail Collins in the October 12 Daily News, after watching Kitty Dukakis handle a small snafu on the campaign trail:

Kitty Dukakis just keeps smiling.

“Is there, um, a time frame here?” she asks no one in particular.

Dukakis has developed a method of talking while smiling for the cameras. lt looks a little peculiar—as though she were constantly baring her teeth. But valuable seconds are being saved!

Here is Denis Hamill, Pete’s brother, in the November 2 Newsday, on the denouement of a discussion between two Irish immigrants, James and Patrick Folan, and a Hungarian immigrant named Andreas Doczy, “about the merits of their respective ‘old countries’”:

The three of them wound up on the sidewalk outside. Doczy received a broken nose. He left and went home to College Point where he pocketed an illegal .32-cal. hand gun. He returned to the bar, fatally shot the two brothers, and then strolled down the block and had a fish dinner in a Greek restaurant.

New York, the League of Nations.

And in the October 11 Post, here’s Jerry Nachman in the middle of the Mets/Dodgers National League Championship Series, explaining New York’s ancient anti-Dodger venom:

Every bad thing in our lives dates from the cowardly decision to pull the Dodgers out of Brooklyn. No one can remember anything bad ever happening before the end of the 1957 baseball season.

There was a tiny but wonderful amusement park at the corner of Flatbush and Caton Avs. And the Prospect Park Zoo had animals to stare at, not pity. And there was a working and vibrant movie house on every other block from the Park to Brooklyn College. And men got off the subways with their sons and the kids ate pistachio-favored soft ice cream and walked over to Ebbets Field….

As far as I’m concerned, the escalating battle of the columnists is the best part of the great New York newspaper war. When their writing is strong, and it usually is, they can give you your bearings in the news-and-information fog that smothers the city, even when you disagree with them. They are fiercely populist, most of them, quick to comfort the afflicted. And afflict the comfortable: Jimmy Breslin and Robert Reno even debated on October 13 and 14 in Newsday about just why it is that real estate entrepreneur Donald Trump is so awful. Breslin took a look at a studio apartment in Trump Parc, on Central Park South, which was going for $325,000 although “the Trump full-page ad for his building was bigger than the apartment.”

I walked from the Trump Parc to Fifth Avenue and then passed the Trump Tower, this brown glass building whose cheap architecture bawls one word into the sky over a once beautiful avenue: greed.

Yet the man whose name is on it, Donald Trump, can stand and say that it is one of the wonders of the eye and everybody in this city of rich sheep cries out that, most certainly, the Trump Tower is true grandeur.

Reno, in his lively and wide-ranging economics column in the business section, contended that the problem with Trump is not bad taste or morals, but that he represents the failure of the Reagan economy:

Trump, naturally, imagines that it takes great and singular genius to make a killing in midtown Manhattan real estate when that market is in its cyclical upswing or to buy a gambling hall and make a profit from games in which the customers, by law, always lose in the aggregate. What’s discouraging is that the Reagan era has not produced more billionaires capable of building factories that can compete with the Japanese, businesses that would create thousands of high-paying, permanent productive jobs instead of new positions for yacht stewards. If it had, they could be as insufferable as Donald Trump and who would care? They could eat off their knives, throw food at parties…

Newsday’s formidable phalanx of columnists includes three Pulitzer Prize winners—Breslin, Sydney H. Schanberg, who moved his op-ed city affairs column over from the Times in 1986, and the venerable Murray Kempton, who spins out his elegant thoughts an incredible four days a week. (“Oh well, I shall vote for him,” Kempton wrote about Michael Dukakis on October 21, “and am consoled for that cheerless duty by the powerful suspicion that the heart saddened by the news that he won’t be president would not be especially uplifted if be were.”) The paper installed James A. Revson, a son of the co-founder of Revlon inc., as a watchdog of the charity-ball set in a twice weekly “Social Studies” column. There he accused Aileen Mahle—known as “Suzy” in her Daily News gossip column—of listing guests at a high-society party she never attended, a flap known briefly last spring as “Suzygate.”

In another smart move, Newsday established an “In the Subways” column; writer Jim Dwyer has brought this world, in which 3.5 million New Yorkers spend part of each workday, to life, and his encyclopedic knowledge of the system keeps him a car’s length ahead of everybody. On October 13, after a water main burst and shut down subway service on the west side of Manhattan, Dwyer found out that three brand-new pump cars, bought for $650,000 apiece to deal with just such a problem, had failed to operate. Then he backed up and described how an engineering decision made around the turn of the century by a man named William Parsons was responsible for the flooding—all of this in some 800 neatly turned words that concluded this way:

The water lapped over the tracks and onto the platforms, giving the flooded stations the look of Venetian canals.

The trouble was confined to “the 1, 2, 3, A ,C, K, D, E , and F [lines],” reported [Transit Authority] President David Gunn. “Other than that, everything was fine.”

Breslin’s farewell to the News was a single line at the end of his May 22 column: “Thank you for the use of the hall.” By the time he started up in his new space at Newsday, the News’s “new generation of voices” was adding a new dimension to New York journalism. Among all the major front-of-the-paper news columnists in the city, Gail Collins is the only woman, Juan Gonzalez the only Hispanic, and Bob Herbert the only black. (Mike McAlary, the fourth part of the News‘s “new generation,” is a member of the best-represented ethnic group among New York’s tabloid columnists, the Irish.) Some 42 percent of the News‘s readers are black and some 28 percent are Hispanic. “There’s finally a recognition that the paper has got to address a whole new constituency of readers,” says Gonzalez.

The News‘s new generation can bring a special resonance to certain issues. Here’s Herbert, for example, on the political geography after the ’88 campaign, in a column that started off about an arson fire that killed a three-year-old boy:

There was no danger of any politicians showing up because this was 125th St. and St. Nicholas Ave. in Harlem and the politicians seek their votes elsewhere. Even Dukakis, whose people complained loudly about racism in the Bush campaign, had to be dragged kicking and screaming into Harlem for the briefest of appearances.

Now we hear that Bush has nominated his campaign manager, James Baker, to be secretary of state—the man in charge of the country’s diplomats. Maybe Baker can appoint an ambassador to Harlem and the South Bronx, somebody who will tell the next president what is going on in these remote regions.

On the other hand, none of these four columnists seems boxed in by category, and to my mind they give Newsday a serious run for the money. McAlary and Herbert are excellent reporters as well as strong writers; Collins wields a delicious wit; Gonzalez, although he swings from the heels and misses sometimes, can hit the long ball. On the day I spoke with him Gonzalez had just learned that his October 11 column had helped one Gary Nieves, a Puerto Rican meat-company worker in desperate need of a liver transplant. When Gonzalez discovered him, Nieves was being shuttled between bureaucracies in New Jersey, none of which seemed eager to pay for his operation, while his weight dropped from 165 to 128.

Gonzalez’s column triggered action from both New Jersey senators and the local Medicaid office suddenly found a shortcut through the red-tape jungle. (Unfortunately, Nieves died while awaiting the liver transplant.)

None of these writers is always good, of course. It would be okay with me if Pete Hamill would stop analyzing the character deficiencies of baseball pitchers just after they lose crucial playoff games. McAlary could get along fine without describing his victory in a bar brawl, as he did on an apparently desperate Sunday in mid-October. Even Breslin one day gave us an argument with his wife, made interesting only because it was about the price of a pair of shoes that cost “more than the people I write about live on for most of a year.” Breslin is reportedly earning more than 400,000 Times Mirror Co. dollars, adding an interesting tension to his underdog instincts. But writing three times a week is hard enough; hitting the ball out of the park with such regularity is something else again.

One way to get a fix on New York’s tabloids is to watch them scramble onto a big breaking story, and the biggest one in New York this autumn came on the night of October 18. At a few minutes after seven that evening, Chris Hoban, a twenty-six year-old undercover policeman, was shot and killed during a buy-and-bust operation in an upper Manhattan drug den. About three hours later and fifty six blocks to the north a second cop, twenty-four-year-old Michael Buczek, was killed by a man with a semiautomatic weapon, after Buczek had ordered him to halt. Since it was widely suspected that Buczek’s killer was connected to the heavy drug trade in the area, the two incidents marked a grim historical milestone for New York in its losing battle with narcotics.

Only the News seemed to sense this in time for the next day’s paper. Everybody played it on page one, but the Post devoted the bottom of its front page to yet another dubious Mike Tyson story—IRON MIKE EXCLUSIVE: THE GIRL I WISH I’D MARRIED. Newsday even had a baseball score among the three stories it hyped along the bottom of the page, under a graphic of a police shoulder patch that could have illustrated a story about any police matter. The News got it right from the start, an all-black front page with the head written in white: 2 COPS SHOT DEAD, and underneath, 3 MILES & 3 HOURS APART.

The contrast in editorials on the day after the deaths is also telling. The Post, where Murdoch’s man Eric Breindel still rules the edit page, pushed the death penalty and listed all the members of the state legislature who had voted against it during I988. (Breindel’s column that day, an anti-Dukakis piece unrelated to the police murders, featured a bracing dip into red-baiting.) The News didn’t have much of a thought beyond anger on the first day after the shootings, but the day after that it would argue—in an editorial titled TWO DEAD COPS AND A PAPER WAR—that drug interdiction at our borders isn’t working and that the real battle ought to be “making people stop using the stuff. That means education. That means treatment. All of that means spending some money.” Newsday urged governor Mario Cuomo to convene a drug summit conference of all the city, state, and federal officials involved with the war on drugs, to draft a coordinated plan, and to appoint a city wide drug czar to run it.

On the 20th, as it turned out, in the wake of this tragedy, candidate George Bush, the federal drug czar at the time, came to town. And more than any other print or electronic media that I am aware of, New York’s tabloids recognized the moment for its flash of insight into the schizoid crime-and-drugs debate of the bitter presidential campaign. Senator Alfonse D’Amato introduced the vice-president as “George Bush, who supports the death penalty.” The vice-president, standing in a sea of blue at Christ the King High School in Middle Village in Queens, accepted the endorsement of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association and basked in what was essentially a death penalty rally, complete with high school cheerleaders who, as the News‘s Lars Erik Nelson noted,“cheered themselves hoarse at every mention of death.”

And Bush accepted something else, the police badge of another dead cop, a rookie named Edward Byrne, who had been shot in the head point-blank in February as he sat on guard duty in a patrol car outside the home of a Queens drug case witness. Byrne’s father, Matthew, laid out a heartfelt case for capital punishment, based on the yearning for justice and revenge: “When a police officer or a law-abiding citizen is killed by someone in this state or in this land, the criminal has inflicted his private death penalty on us,” Byrne said. “When some mutt decides to murder a cop or a civilian the victim does not get assigned counsel, the victim does not get a judge, a jury, or a trial. And the victim certainly does not get an appeal; there is no appeal from the barrel of an assassin’s gun.”

While the tabloids’ news columns told that story, columnists at all three papers brought up some other associations with the words “Bush” and “drugs” and “crime” that did not get mentioned at Christ the King.

Breslin, the new columnist at Newsday, wondered whether the candidate would tell the families of the dead officers

how he could have a drug supplier on a government payroll. As nobody in this city would ask this of him without fainting, Bush will address high school students and then appear at night at the Al Smith political dinner, where there is no recall of Bush’s role in drugs, and all will stand and drip tears for the two dead cops and then sit down and eat roast beef.

McAlary, the new columnist at the News, wrote:

More than a dozen New York City cops have been killed by drug dealers while Bush watched our borders, rushing from one place to the next to incite frightened people into voting for the death penalty. We are asked to forget that part and believe that Dan Quayle…will keep drugs from our cities. But the idea of Dan Quayle, drug czar, should not give cops a whole lot of confidence. Quayle, after all, has always left the business of warring to other men.

Pete Hamill, the new columnist at the New York Post, noted that Quayle’s “major handler,” Stuart Spencer, took $350,000 from Manuel Noriega during 1985 and 1986 for public relations work, an attempt to polish the Panamanian strongman’s image. Noriega had needed such a polishing, Hamill noted, because an opposition leader, Dr. Hugo Spadafora, had brought evidence to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration indicating that Noriega was running drugs, and in September 1985, Spadafora had been murdered. Hamill quoted from an account of his death:

…his testicles were crushed, a pole was forced up his rectum, the insignia F-8—the calling card of one of the Panamanian Defense Force’s death squads—was carved into his back…

Noriega is still in power. Young men named Hoban and Buczek have joined the giant mound of the dead…

I expect this Bush visit was handled differently on MacNeil/Lehrer. I don’t know, because when you are reading a couple of solid tabloids a day something has to go. But I doubt that viewers had to feel the heat of Matthew Byrne’s rage or ponder Dr. Spadafora’s final moments. If past form is any guide, I expect the hosts invited a couple of surrogates for the candidates to block and check each other’s moves, maybe a drug or death-penalty expert from the world of academia or law. Then, Goodnight Robin. Goodnight Jim. Get some rest. Robin was looking a little wan last time I checked in. He should take two tabloids and call in the morning.

–Mike Hoyt (Originally published in print with the title:

“NY tab-war payoff story!”)

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.