Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Editor’s note: After publication, Twitter restored the author’s account, noting in an email that, while it takes violations of its rules seriously, “it looks like we made an error.”

I’M A TRULY MARGINAL TWITTER USER. Or at least I was. A late adopter in recent years, having worked in and written about politics and the press, I started following journalists, scholars, public officials, and a handful of institutions I know, respect, and work with. I sometimes retweeted things to show my support and have sometimes commented on others. I’ve never had any interest in attracting thousands of followers, engaging in toxic tweet storms, or “elevating my brand.”

Given the relentless Trump-driven political press curve, I deleted my account for a while a few months ago. As a lifelong news junkie, I was among those who found it too distracting from other parts of life and work that called for more sustained attention. But I missed it. Earlier this summer, I dipped back in.

Last week, I replied to a tweet from historian Michael Beschloss—which had been retweeted by anti-Trump GOP attorney (and spouse) George Conway—after the FBI searched Mar-a-Lago for classified documents. Beschloss pointed out the irony that “Trump’s lawyer and pal Roy Cohn reviled the Rosenbergs for passing out American nuclear secrets.”

Here’s what I wrote:

“@BeschlossDC @gtconway3d Not merely reviled, but prosecuted them and put them both — two parents of young children — in the electric chair at Singsing [sic].”

A few days later, Beschloss himself tweeted a similar comment—“Rosenbergs were convicted for giving U.S. nuclear secrets to Moscow, and were executed June 1953”—above an iconic photo of the doomed couple in custody.

But for my fast-thumbed typo in Sing Sing, so far, so good when it comes to reciting basic facts about an infamous event in American history.

Turns out, not so much on Twitter, which a day later locked me out of my account for an alleged violation of its rules “against abuse and targeted harassment.” Did I abuse or harass the sainted memory of Roy Cohn, who died in 1986? If so, somebody better tell Tony Kushner not to tweet about Angels in America.

We know this is a moment of real concern about violent threats on social platforms—and since January 6, actual violence, especially in recent weeks—overwhelmingly from the Pro-Trump Right. I very much share the concern about how social media has supercharged and mainstreamed long-standing forces of violent extremism in American life. So I figured the easily triggered Twitter algorithm simply couldn’t recognize the obvious context of what I wrote. As we all know, artificial intelligence can turn out not to be so intelligent.

In an email appealing my suspension, I explained that I was commenting with purely factual statements about a well-known legal and political case from seventy years ago, involving the long-deceased figure Beschloss had himself cited. Surely, actual people would realize this error in flagging this uncontroversial and purely historical statement as abusive.

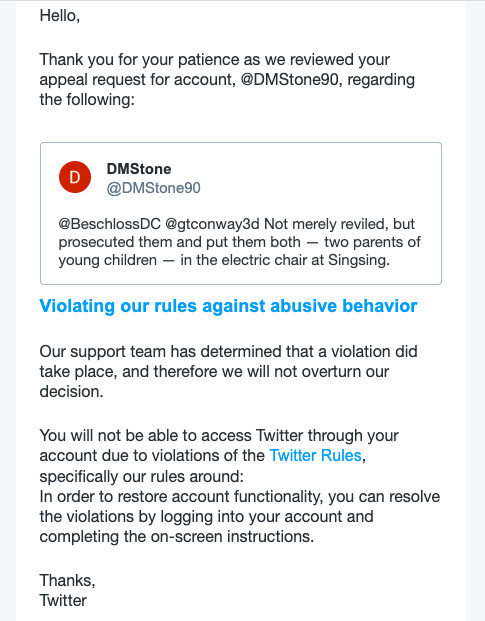

Yet here’s what I got back:

Wait, what? Sentient human beings at Twitter actually looked at the facts of this matter and upheld my ban? For both personal and professional reasons, I was shocked.

First, I started out as a First Amendment media lawyer and years ago published a history of President Nixon’s efforts to muzzle editorial freedom on the then-fledgling PBS. And for much of the past two decades, I worked for one of the nation’s leading free-speech scholars, Columbia president Lee C. Bollinger, and with a whole ecosystem of faculty and programs—including this publication—addressing the complex issues of social media and free press and expression in the digital age.

So I fully appreciate that privately owned social platforms are not subject to the First Amendment’s safeguards against government censorship, which don’t control contractually agreed-to terms of service. And unlike the worthy clients of our Knight First Amendment Institute’s successful litigation against President Trump for blocking some followers he didn’t like on Twitter, my situation obviously doesn’t involve an elected official effectively turning his Twitter feed into a public forum subject to constitutional protections against viewpoint discrimination.

But even if my bar membership has long since lapsed, you don’t have to be an expert to know Twitter’s decision in my case is perverse. And for me, it felt personal. I grew up in liberal New York City during the 1960s and ’70s. My late mother’s idealistic first vote in 1948 was for third-party Progressive presidential candidate Henry Wallace—FDR’s former vice president for whom successor Harry Truman wasn’t nearly liberal enough. In those early Cold War years, she told of being briefly sent home from the midwestern liberal arts college she was able to attend on scholarship for protesting the school’s dismissal of a popular faculty member and his librarian wife for alleged radical views, triggering the resignation of several supportive faculty members, including the college’s only Black professor, in principled protest. For my mother and many other liberal Jewish New Yorkers of my youth, Cohn’s malevolence personified the Red Scare that damaged so many lives and careers in the world that he himself had grown up in and turned on.

Despite her usually reserved manner, I was probably a teenager before I realized that his full name wasn’t “that prick Roy Cohn” given how my mother would refer to him whenever his name would pop up in the local news before any of us had heard of Donald Trump. And, remarkably enough, decades later the last TV shows she and I watched together while she was in home hospice were HBO’s beautiful filmed versions of Angels in America—with the second part coming as her own declining condition strangely echoed that of the venomous character onscreen haunted to the end by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg.

Of course, I never called the disgraced, disbarred, and long-deceased Cohn any abusive or harassing names in my tweet. I didn’t suggest in any way that what happened to the duly convicted Rosenbergs or the many victims of his boss Joe McCarthy’s sham hearings should be done to anyone else. I simply elevated the irony of Beschloss’s tweet with a few added facts about the twentieth century’s most prominent American espionage case.

Twitter now confronts me with a page explaining that I can have my account restored after a twelve-hour period if I “Delete the tweet that violates our Rules.” I’m sorry, Twitter, but I’m not going to accept your mistaken ruling by going back and deleting what I wrote. I’ll miss following along, but I’m going to honor my late mother’s memory, the historical record, and basic common sense in standing by my factual comment about that prick Roy Cohn.

An earlier version of this story inaccurately referred to a college’s “dismissal” of a Black professor, who in fact resigned in protest. CJR regrets the error.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.