Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

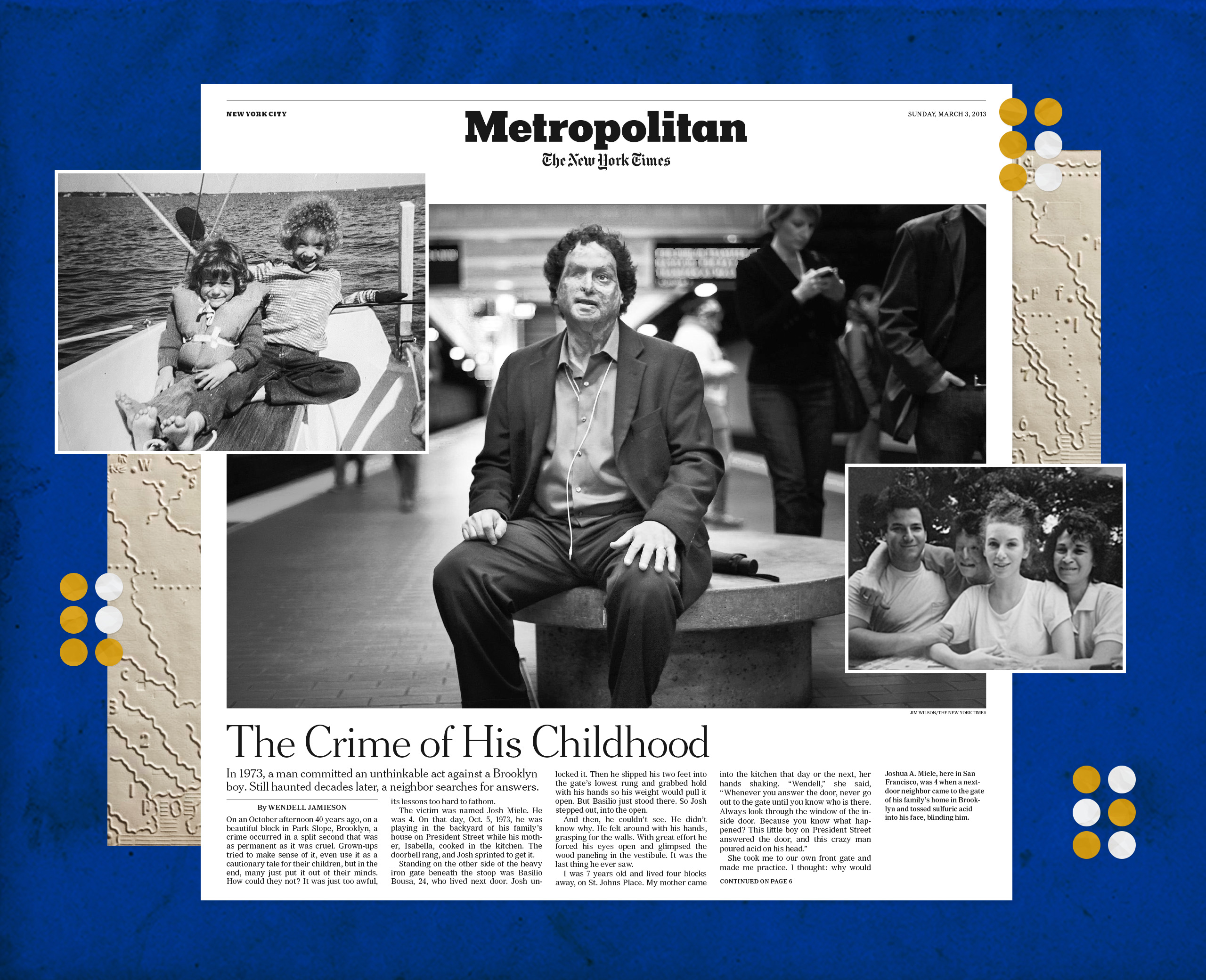

On October 5, 1973, Joshua Miele, then four years old, was burned and blinded when a delusional neighbor poured acid on him in Park Slope, Brooklyn. In 2021, married with children and living in the Bay Area, he won a MacArthur “genius” award for his work developing technology for blind people. Several years before he won the award, he was profiled in the New York Times. In this excerpt from his new memoir, Connecting Dots: A Blind Life, Miele recounts the delicate dance between subject and writer that led to that story, while providing a primer on the tropes and clichés journalists should avoid when writing about disability.

I almost never checked my spam folder, but one day in September 2012, I happened to, and there I found a short, recent, and curious email.

Its subject line said simply, “Hello from New York.” The body read in its entirety:

Dear Dr. Miele:

My name is Wendell Jamieson. I am trying to get in touch with the Joshua Miele who grew up in Park Slope, Brooklyn, as I did.

Have I reached the right person?

More interesting than the note was the New York Times email address from which it came.

Well now, what do we have here? I told Wendell he’d gotten his man and asked what I could do for him. He emailed back quickly that he’d like to discuss writing a story about me, about my being burned, about my recovery, and about the work I was doing now. He said we’d never met, but like others in Park Slope he’d been so affected by what happened to me that, even now, when he was forty-six, he felt a sense of dread when he answered the door beneath the stoop when he visited his mother’s brownstone, five blocks from President Street; that’s how deep in his psyche lurked that dark neighborhood legend, the Acid Man.

It had been thirty-nine years since I got burned, and the initial press interest had long ago faded. But I always had this sense that sooner or later, another reporter would call to check in on me. Now that the call had come, I experienced a mix of emotions. My first one? No way. No thank you.

I could imagine it all: the heartwarming tale of a poor little blind boy overcoming adversity to live a “normal” life. And burned with acid, no less. What a trouper! What a plucky, brave little soul! And some kind woman even married him! Let’s all pity and celebrate him.

I didn’t want to excavate my past for the world to see. I worried that I would lose credibility in the science world by talking about myself, that this would be some kind of inspiration porn at which the world would stare even as it wanted to turn away.

I started to reply with a polite decline, even typed a few lines, but then something made me pause. I didn’t want to be known for what happened to me, but I couldn’t deny that I wanted to be known. And I’d had some successes—my new tactile maps were being produced en masse, and my tactile-audio maps of the BART transit system were coming together beautifully; YouDescribe, my app to allow crowdsourced audio descriptions of YouTube content, was set to launch in a few months. I had a bunch of other interesting projects moving along, in areas like accessible STEM education and mobile wayfinding tools. And I had recently been named chair of the board of the LightHouse for the Blind in San Francisco. I knew a story in the Times would inevitably put a lot of focus on the sensational details of the attack, but maybe that would be worth it if I could minimize that and tell the world about all the cool things I was doing now.

I faced one other quandary: Would I be exploiting my own childhood trauma for gain as an adult? I decided that if anyone had a right to do that, it would be me.

The truth is, I never thought about what had happened and I never felt a hint of anger about it, even for one second. It sounded like Wendell thought about it more than I did. I hadn’t talked about it for years, maybe decades. Being a crime victim just wasn’t my identity.

But I certainly did feel anger at those in society who marginalized disabled people, or those who failed to think of even the simplest solutions to make our lives livable, like the designers of early bank ATMs. Being burned was just something that had happened a long, long time ago.

I told Wendell I’d think about it. Then I invited him to meet me the next time I was in Brooklyn to visit my dad, and a few weeks later we sat down at a new Scandinavian-themed coffeehouse in Park Slope. He seemed like a nice enough guy, with two children just a little older than mine. The coffees were ridiculously expensive, but that was okay because the Times was paying. We joked about how the neighborhood had changed since we were little, how the biggest danger these days were au pairs aggressively piloting double and even triple strollers down the sidewalks.

When I got back to California, I asked Wendell to send me a few stories he’d written, and, while they were interesting, all set in Park Slope, they skewed a little too nostalgic, a little too sentimental, for my tastes. I told him so. If I did the story, I admonished him, it couldn’t be at all sappy. He seemed a little taken aback but said he’d do his best.

Then he cautioned me: “If we move forward, you’ll have to put yourself in my hands a little bit.”

Now, that was scary. I didn’t like putting myself in anybody else’s hands.

I couldn’t decide. I sought counsel from friends old and new. Jon, the “manager” of my high school band, who always had a cool head about these kinds of things, was on the fence. Same with my wife, Liz. She worried that the story might draw undue attention to our children. “There are a lot of nuts out there,” she said.

But any story wouldn’t just be about me: everyone in my family would have to be included. I’d need their buy-in. So as I weighed the pros and cons, a flurry of phone calls and emails ricocheted around the country as I asked everyone what they thought. Nearly forty years had gone by, but now the true narrative arc of that dumped cup of sulfuric acid, of the damage it did in seconds, of the long, tangled journey in the aftermath—much of its lingering pain buried and much of it unknown to other players, even if we’d become as close as any family could be—would be laid bare.

My dad was retired and lived on Carroll Street in Park Slope with his wife, Lori, and their daughter, Emma. He loved the idea of a story in the Times; his quick thinking in the hours, days, and weeks after I got burned had saved my life and helped my recovery.

My mom lived in Rockland County with my stepfather, Klaus. She was hesitant; did we really want to dredge all that up, and who was this Wendell guy, anyway? But she said she’d respect my wishes.

Julia, my sister, lived in Park Slope with her husband and their children. She was a professor at CUNY and had a PhD in English, but her main focus was disability studies. I was partially responsible for this choice. Having a blind little brother had certainly affected her worldview: as she studied literature, especially Victorian literature, and even before that, she found she was drawn to stories of the blind and otherwise disabled and the role they played in fiction, movies, and other facets of life.

She was against participating. She worried, as I had, that it would simplify my complicated life of ups and downs into a black-and-white narrative of inspirational overcoming, that the mere fact I could put my pants on in the morning would be celebrated as miraculous. But she had another reason: she was a terrific writer, and she’d harbored ideas of one day publishing a book about our family story herself. Who was Wendell to come take the story away from her?

In the end it was Jean, my big brother, who clinched it for me.

His journey had been a long one, one that had begun from a place of true anger—the anger he’d taken on, perhaps, for the whole family—but which had now brought him to a place of calm and contentment, even wisdom, that was remarkable.

He was the most thoughtful of my conversational partners as I wrestled with the idea of participating in this Times story. He listened, he advised, he offered points and counterpoints. We talked about how my experience, and my successes, could help people who weren’t as far along as I was in their journeys of blindness or being burned, or at least show them there was a path forward. And then he said this: “When the universe presents you with an opportunity, just say yes.”

He was right. I’d come to realize that this story could make a real difference. My visibility could be a real public service.

I told Wendell I was in.

The story took months—Wendell disappeared for a few weeks dealing with Superstorm Sandy and its aftermath. In time, he spoke to everyone in my family. He also tracked down Carmen Bouza, the sister of the man who had poured the acid on me, and Col. Basil Pruitt at the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, who had led the team that treated me; both acted as if they’d been expecting his call, as I had.

Carmen Bouza started to cry when he introduced himself over the phone and told her why he wanted to talk. And even though nearly forty years had passed, Colonel Pruitt recounted with cool military precision the specifics of my injuries and treatment without consulting any notes or records. He said he had used slides of them to instruct generations of Army burn specialists.

I met with Wendell several more times in Brooklyn, and then he flew out to California. We had bourbon at John’s Grill in downtown San Francisco—fabled haunt of Dashiell Hammett—and then took BART to Berkeley for sushi and sake at the house with Liz and the kids; my daughter, Vivien, now seven, and heavily into musical theater, performed an a cappella rendition of “Tomorrow” from the musical Annie after dinner—her voice was beautiful and clear like a bell, with not even a hint of nervous vibrato, and I couldn’t have felt any more proud and content as those surprisingly robust tones filled my home. The next day, Wendell came over to the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute, the nonprofit where I worked, and played with a BART tactile map and tested a beta version of YouDescribe.

It was great fun—I liked talking about myself. But this trip down memory lane wasn’t joyous for everyone. My mother struggled. She went back and forth about whether she wanted to participate. Klaus, my stepfather, would later say she seemed distracted and out of sorts during this whole process; usually, she was as sharp as a blade. There’s no better way to demonstrate her emotional turmoil than by reading her own words in emails she exchanged with Wendell.

“It’s still an open wound and most probably will remain that way until the day I die. I keep it carefully insulated so it doesn’t color my functioning daily life…but it’s always there. Once open, I have things to say, but not sure how far I want them heard.

“I think our family is stronger for having this as part of us. I believe something similar of all people who become parents: they’re stronger people than those who are not. Are you a parent? Can you imagine something like this happening to your child?”

“The Crime of His Childhood” ran on March 2, 2013, on the cover of the Times’ Metropolitan section, and spent some time at the top of the homepage that afternoon. As I had feared, the story was mostly about the attack and my recovery; I sighed when I read the headline. But the story did include a healthy chunk about all the stuff I was doing.

The story contained some revelations: my assailant had died of emphysema in 1992 after moving to Florida, and in moments of lucidity was horrified by what he’d done, his sister Carmen said. “Nothing was ever the same after that day,” she told Wendell, crying. “This thing destroyed my family.”

The irony was clear: It had not destroyed my family. It had shaken it, it had rocked it, and it had affected everyone deeply and still did—just look at Julia’s and my careers, and my mother’s struggle—but here we were, stronger than ever.

The online views were through the roof—though for proprietary reasons Wendell wouldn’t share exact numbers—and soon the story had hundreds of comments, all more or less the same: I was a fine fellow, an inspiration, a great guy. I guess I can’t control what people think. The following week several people introduced themselves to me on the street or on BART.

My father heard from acquaintances far and near about what a great guy he was. Jean also heard from friends old and new, with many apologizing for not realizing what he was going through as a teenager and for not being more sympathetic or patient with him.

Julia’s response was more complex. She thought Wendell had done a good job but perhaps had defaulted a bit too much to the stereotypical trope of the struggling disabled person overcoming adversity against all odds. She expressed this very publicly: she wrote a letter to the editor critiquing the story, which the Times published the following week.

“I am concerned that some readers will see Josh’s success in relatively simple terms: he was victimized; he struggled; he overcame,” she wrote. “Obviously, his life, like all lives, is more complicated than that. And it is critically important that we be open to many different kinds of stories about disability, especially those that are complex and open-ended, and especially those that people with disabilities tell themselves.”

And my mother? She sent Wendell a single email: “Nicely done.” Coming from her, that was a rave.

I hadn’t been allowed to read the story before it was published, so when it finally came out, I read it with some trepidation. I had worked hard with Wendell to make sure he understood about “inspiration porn” and the tired clichés associated with injury and blindness, and while he seemed to be paying attention, I couldn’t be sure if all my lectures had landed. I had gambled with my story, put myself in someone else’s hands, but as I read I realized I had mostly won—Wendell told the story of my getting burned with good taste and decent sensitivity to disability. And I marveled at how my story seemed to resonate so powerfully with so many other people, and how it remained embedded in the collective psyche of Park Slope while to me it was just a distant memory.

But most importantly, my work on accessibility and digital equity for blind people had made it to the top of the homepage of the New York Times. I felt like it was a pretty good trade.

Excerpted from Connecting Dots: A Blind Life by Joshua A. Miele with Wendell Jamieson. Copyright © 2025. Available from Grand Central Publishing, an imprint of Hachette Book Group Inc.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.