Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Next week, the Democratic National Convention returns to Chicago. It’s the same host city as in 1968, a year when fraught proceedings inside the convention hall were overshadowed by a violent police crackdown on antiwar protesters outside. (Thomas Whiteside reported on the scene for CJR.) It was a time of political upheaval that sounds familiar today: a Democratic president dropping out of the race, assassinations (or attempted ones), and protests against police brutality, racism, and an unpopular war.

America is, of course, a very different place than it was fifty-six years ago, but the events of 1968 resonate today, especially for those who covered them. “The similarities are striking—and, I think, they may be misleading,” said Robert Friedman, who watched history unfold from his perch as the editor in chief of the Columbia Spectator (where, just like this year, antiwar protesters took over Hamilton Hall). “The worst experience that I had as a reporter was the convention in Chicago in ’68,” recalled Earl Caldwell, a longtime correspondent for the New York Times who covered the civil rights movement, and was in a motel room below Martin Luther King Jr. when he was assassinated. Dan Rather, who found himself caught up in the melee inside the convention, said, “In Chicago in 1968, you knew it was the story and, to quote one of the sayings at the time, the whole world was watching.” What the world saw on their television screens marked a turning point in the public’s perception of the media, with many blaming what occurred on the reporters, according to Heather Hendershot—a historian and the author of When the News Broke: Chicago 1968 and the Polarizing of America (2023). Hendershot spoke to my colleague Josh Hersh for an episode of The Kicker: “After the convention, the idea that the mainstream media…were exhibiting liberal bias became nationalized.”

Over the past few weeks, I spoke with these and other journalists to hear their recollections of that time—and to find out what they make of comparisons to the politics of 2024. Our conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

Marvin Kalb

Chief diplomatic correspondent, CBSNineteen sixty-eight was an astonishing year. The year started with the Vietcong’s total surprise Tet offensive, which caught the United States totally off guard. The next major thing was that the president, having been asked for an additional 206,000 troops, thought about it and said, I’ve got to get out of here. At the end of March, he announced, to everyone’s astonishment, that he was not running any longer. Almost immediately, Martin Luther King was shot. The minute that happened, almost every major city in America was in flames. People killed. The country appeared to be collapsing. A month or two after that, Robert Kennedy gets shot and killed.

Robert Friedman

Editor in chief, Columbia SpectatorIt is important to remember how crucial the Vietnam War was in defining America in 1968. There were two huge issues: one was race and the other was Vietnam. The race issue was best exemplified by the assassination of Martin Luther King and the riots that occurred in many cities around the country after that. In terms of Vietnam, the protests were all-encompassing. The difference from now is that the Vietnam War actually involved US soldiers, a whole generation of college students facing a draft, and thousands of American deaths. It shaped American consciousness. War is terrible wherever and whenever it occurs, but the personal jeopardy is missing.

Earl Caldwell

National reporter, the New York TimesOne of the biggest stories in this period was the story that was taking place in these newsrooms because they were integrating. In 1968, it was the year the Kerner [Commission] report came out. The most damning part of that report was aimed at the institution of the news media. The reports said that these papers could not tell their readers what was happening in Black America, even if they wanted to, because their staff were all white.

When you were Black—“Negro” then—nobody thought you were the reporter. My world really changed when I joined the New York Times and I became a national reporter. I’d arrive at these places in the middle of the night and I’d go into these hotels and say, Earl Caldwell, and they said, Oh, we don’t have any reservation for you. Then I would say, Maybe the reservation’s in the name of the New York Times? And they’d go into a back room and come back and say, Oh yeah, we do have it. They see a Black face show up and that’s the last thing they expect.

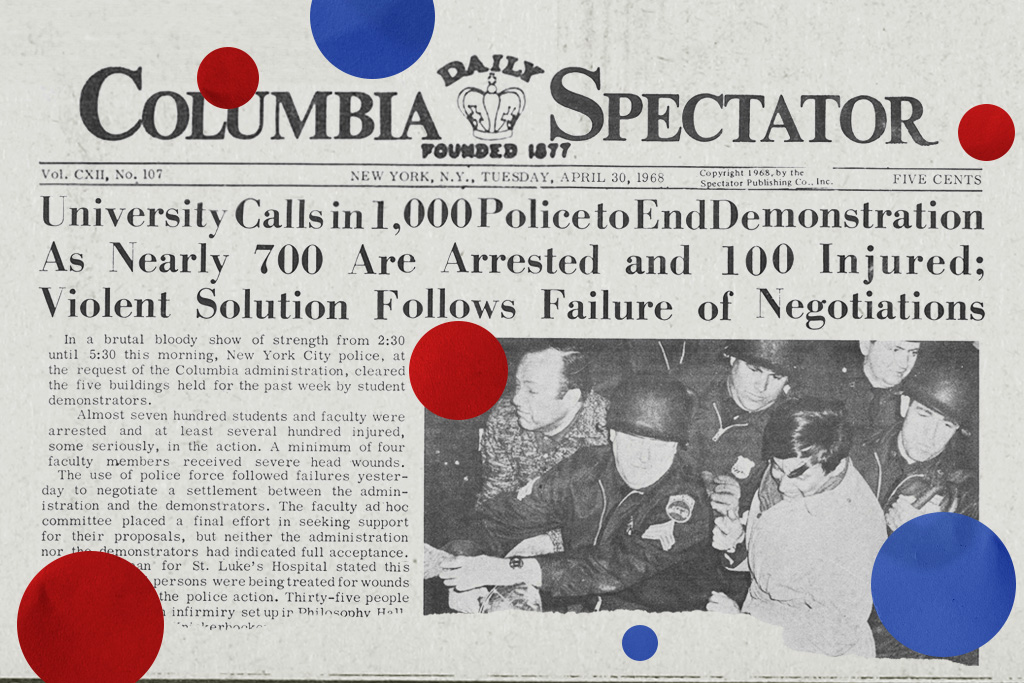

Friedman

On April 30, 1968, the police were called onto the Columbia campus. Seven hundred students were dragged out of the buildings, arrested, some were beaten. It was a pretty horrific night. My deputy editor was among those beaten by the police and hauled off to prison—I had to call his father at three in the morning to tell him that his son was in jail. The next morning we woke up, and on the front page of the New York Times was a story written by then–executive editor Abe Rosenthal, about the terrible damage that the students had done inside the buildings. What I saw was the terrible damage the police had done on campus—beating students, bloodying them, arresting them. What the Times saw was what the Columbia administration wanted them to see, which was ink thrown on the blackboard in Mathematics Hall and the sleeping bags strewn across the hall of the office of the president.

Caldwell

With King, I was actually missing my deadline because I wanted to get a telephone in my room. The operator told me that they didn’t have any service. She kept telling me that the lines were busy. I said, I’m a reporter from the New York Times. She said, I don’t care who you are. When this thing happened with King, I got up off my behind and there was a payphone out in the alley just behind the restaurant there.

I called the New York Times and asked for the national desk and a secretary answered. I remember telling myself to be calm, be cool. I told the secretary to tell them it’s an emergency. Then I just told him what had happened. The key thing he asked me was if King would survive. I was able to tell him that there was no way he could survive. I mean, I was looking right into his eyes. They looked like somebody had put something in them and stirred them up—his eyes. But the wound was so massive.

Kalb

You go into the Democratic convention, there was wildness all over the place. I’ve never seen anything like it. It was an amazing scene to behold.

Dan Rather

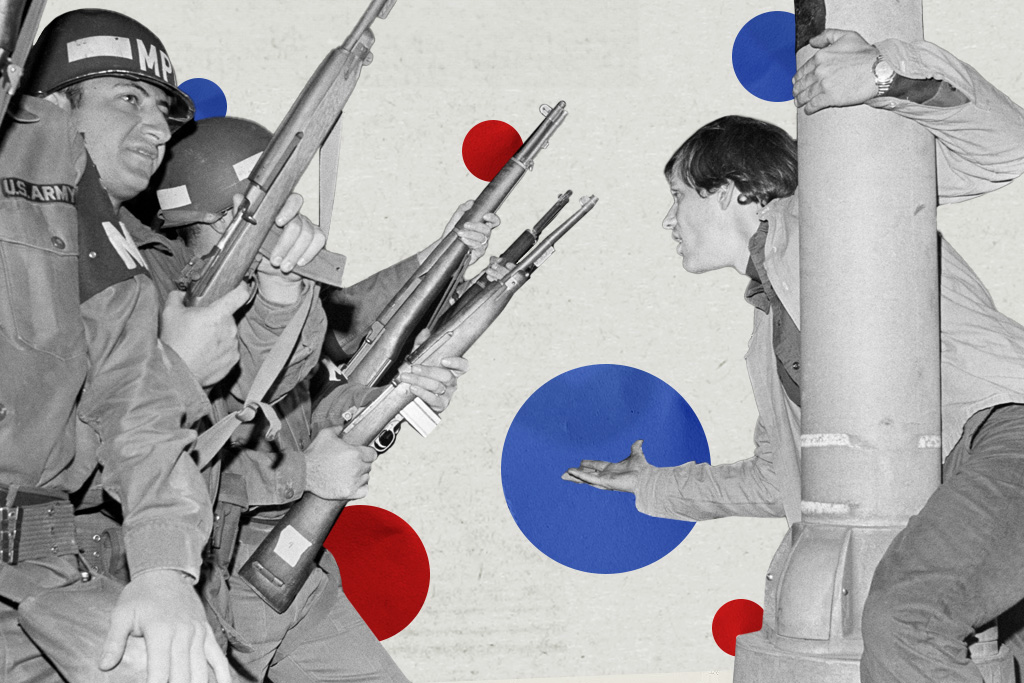

Correspondent, CBSIn Chicago, in 1968, it was electric. You knew it was the story and, to quote one of the sayings at the time, the whole world was watching. There was an atmosphere that was charged, both inside and outside the hall, where there were mass demonstrations. Security was way heavy. From the very beginning, if you were any kind of a reporter at all, you knew that the whole idea was to keep control.

There were layers upon layers of security, including plainclothes policemen and, not only that, but not-plainclothes policemen—enforcers. It made it difficult to get into the hall, and to leave. As you were planning your coverage, and coverage developed, this loomed large. It would be a struggle. It was to be decided at the convention who the nominee would be. As a reporter— speaking for myself, frankly—you didn’t want to be anywhere else during those days.

Caldwell

The worst experience that I had as a reporter was the convention in Chicago in ’68. One of the things that happened was Claude Lewis, my dear friend, was with the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Bulletin. The police out in Chicago, in Grant Park, were attacking the crowds. Claude was holding up his press credentials and they beat him. I found him the next day in a hospital. He still had this little piece of paper—his press badge—and it was bloody. They beat him pretty good. I didn’t get beat up, because I knew when the police started coming what was coming. Outside the Hilton hotel, I’ll always remember what I saw. I’ve never seen anything like it in my life. There was a big crowd of demonstrators outside the Hilton and the police kept converging. The police were about eight, ten deep, taking these little baby steps. They were going close—they inched closer and closer—and, all of a sudden, the protesters had no place to go. They were going to go right through that glass window. Then the police started beating them. I mean, they were beating them. When it was over, I looked at the ground and there were nothing but shoes—dozens and dozens of all kinds of shoes. They beat those kids right out of their shoes. I went into the hotel—you got these little credentials around your neck so people don’t know what you are, but they know you’re official something—and a woman grabbed me, a white woman, and she said, You’ve got to do something! Young white kids! In Chicago, it was the white students, antiwar students that were really the ones that were leading those protests, but they were the targets of the police. I was never in a situation like that where I saw Blacks being beaten the way those kids were beaten out in Chicago.

Rather

In 1968, there was no cable television, there was no internet. You basically had the big three networks, and ABC was not fully grown at that time. All three networks carried all of the conventions…that was about the only place anybody could get it. A huge difference is that things were decided at the convention, as opposed to today, when the convention only rubber-stamps what has been decided in the primaries. You could make a case that it was the last convention where things were really decided.

Kalb

The thing to bear in mind now, we were in a totally different world. Journalism did not have cable television, social media, any of the advantages and problems of the internet. We were still essentially three networks, major newspapers, primarily men doing the reporting, anchoring, and writing for newspapers. Women had not yet really made an impact on journalism, and everything was, I would say, old-fashioned: the way in which we considered stories, the way in which we reported them.

Today I sense much more of an effort to editorialize things than we did back in ’68. In ’68, there was a feeling—and I’m not speaking just for myself, but CBS network, NBC, the Post—that we didn’t feel we were part of the war, or part of the campaign. We were just covering the story rather than being part of this story. Today there is very much a war within journalists and, on both sides, there is a willingness to be inside the story, rather than be above the story looking down.

Caldwell

When I think about it, this would be a very difficult time to be a reporter. I can’t imagine what it would be like to have your editor in your pocket—everywhere you went, all of the time. They have instant contact with you. Sometimes you need to be hard to get. Sometimes you need to be able to have your space. One of the things you need as a reporter is a little bit of time, sometimes, to swallow what it is that you’re witness to. We had that. On the other hand, if you were a reporter in something like what happened to me with King? Oh, my god. It’s amazing what you could do.

Friedman

In some fundamental ways, journalism has not changed. The job of reporters—to witness, confront, and analyze what’s going on—remains basically the same. For me, the education that I got as a student journalist at Columbia in 1968 is basically: pay attention to what people are saying, listen, watch, learn, report, do it fairly, and do it on all sides.

The similarities are striking—and, I think, they may be misleading. History, while it may echo the past, doesn’t necessarily follow it. It would be a mistake to think that the outcomes of the elections or the politics of the times are alike.

In 2024, America is a different country. We are going to have a second Black Democratic presidential nominee. In 1968, that was considered to be an impossible dream. In fact, the one person who came closest to articulating that dream, Martin Luther King, was gunned down. I don’t think whatever similarities—and however dramatic—are between 1968 and 2024, necessarily, can be used to predict what’s going to happen this time around. One thing that’s always a constant: surprise.

Ted Koppel

Nixon campaign reporter, ABCI think this is about as fraught a period as I can remember, including 1968. What is definitely more fraught is what happens the day after. I think if we look back at what happened four years ago, and the election denial that began quite literally on Election Day, and then just built up until it reached an explosion on January 6—if you look back at what happened then and you look at the circumstances today, and ask yourself, what do you think is going to happen if, as is inevitably the case, one or the other side loses? How likely are they to take it in a generous spirit? The danger of real violence after the election is significant.

Kalb

If I was covering the story now, I would want to know as much as I possibly could about Kamala Harris. I would like to know a great deal more than I know about San Francisco politics. I’d like to know the promises that she made when she was just a lawyer, not someone who may be our president. I want to know more about the people. What drives them? What moves them? What defines them? Because ultimately, out of that will emerge the policies that will govern the country and end up governing all of us.

Rather

Going into the Democratic Convention, my one piece of advice I’d have for everybody is, Don’t be cynical, be skeptical.

I tend to give myself a lecture and would give it to anybody else covering politics today: Don’t fall into the trap of spending a lot of time with polls or the so-called horse race coverage. It’s almost not worth talking about, because people are going to do it whether you think it’s a good idea or not. As for yourself as a reporter, you can promise yourself you’ll do as little of it as possible. Keep in mind—as I learned to keep in mind—that, when covering politics, overnight is a long time; a week is forever. What may appear to be the case when you walk out of this Democratic Convention in a matter of days could be something different. In politics, things change really quickly.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.