Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In his recent farewell to a four-decade-long career at The Washington Post, the Pulitzer Prize-winning national security reporter Walter Pincus penned a paradoxical jeremiad about the state of our profession.

He noted the rising influence of such outlets as cable TV and Twitter. But in a world of clicks and strong competitive pressures, he argued, newsmakers are becoming ever more adept at manipulating the media, and “facts seem to be taking a back seat to arguments and slogans.” He lamented that we increasingly inhabit a “PR society,” where “public relations has become a key part of government and our politics.”

The indictment, trumpeted approvingly on social media, was hardly a new one. Anxiety about the role of political PR reached a high pitch after Vietnam and the convulsions of the 1960s. Films such as The Candidate (1972) and books such as Joe McGinniss’ The Selling of the President 1968, about the creation of the so-called New Nixon, decried the triumph of style over substance as a worrisome byproduct of a media-obsessed age.

In Spin Cycle: Inside the Clinton Propaganda Machine (1998), Howard Kurtz offered an intimate portrait of what he called “governing by sound bite.” The book served as a sequel of sorts to Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker’s 1993 documentary, The War Room, which showcased Bill Clinton’s aggressively image-conscious campaign. By the time Spin Cycle appeared in paperback it had acquired a new subtitle, How the White House and the Media Manipulate the News, re-apportioning the blame to both partners in the PR dance. Kurtz, who would move from The Washington Post to CNN and then Fox News, seemed to be spinning his own narrative.

Against this backdrop of cultural anxiety and complaint, David Greenberg, a historian of American politics who teaches at Rutgers University, has written something of a corrective. In Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image (2003), he zoomed in on changing cultural representations of the controversial former president, including those of Nixon’s own manufacture. In Republic of Spin, Greenberg offers a more panoramic view, examining a century of White House news management and image-making and the broader history of political spin.

Greenberg’s achievement lies primarily in contextualizing our current handwringing. He points out that American presidents of the modern era have consistently tried to channel and sway public opinion. He shades the picture with portraits of operatives, from the famous to the obscure, who have aided them. And he takes note of journalists, academics, and others who have deconstructed, critiqued, and sometimes even celebrated those efforts.

Greenberg is a fluid, authoritative writer. But the book’s very ambition invites narrative pitfalls. In covering so many presidential administrations, characters, and incidents, Republic of Spin can seem overstuffed, whirlwind, and superficial–impressive in its reach, but less engrossing than a more focused study might have been.

Greenberg’s essential point is that, for all our worries about the deleterious effects of political PR, the proverbial sky is not, in fact, falling. Or, if it is, it has been descending gradually for a century or more, at least since the administration of Theodore Roosevelt. The goal of shaping (as well as gauging) popular opinion for political ends has remained constant; only the means–from speeches and press conferences to polls and focus groups, YouTube videos and Twitter feeds–have changed.

“Sometimes our politics seem to be nothing but spin–a dizzying cacophonous world of claims and counterclaims … ,” he writes. “We hear that our politics are phony and corrupt; that our leaders are packaged and unprincipled; that their rhetoric is shallow and poll-tested; that even the most important political events–debates, conventions, speeches, interviews, press briefings–are scripted, staged, and choreographed.”

We are told, he adds, that spin “misleads or deceives us,” and that “it chokes off the honest and open discourse that our democracy needs, rendering our politics vapid, artificial, or bankrupt.” What is more, he writes, the White House dominance of spin “plays into long-standing American fears of a too powerful executive.”

Much of this critique–which Greenberg largely rejects–seems to ring true. Vapidity certainly seems ascendant this campaign season. But is spin truly the culprit? Unvarnished prejudices, policy ignorance, and sheer insult seem to have assumed pride of place over the rhetorical polish and deliberateness traditionally associated with spin.

Greenberg’s final point, about fear of a strong executive, is even more questionable. Distrust of Washington and our politics seems to have less to do with the power of the White House than with a pervasive cynicism about the system’s alleged corruption, as well as ideological polarization, unequal distribution of wealth, and legislative gridlock.

In any case, Greenberg wants to reclaim spin, broadly construed, as a valid instrument of democratic discourse. In making his case, he cites Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, in which the candidate of hope and change denounced Washington spin. To Greenberg, Obama’s own idealistic rhetoric was simply another form of spin. As president, Obama later critiqued his own political messaging, worrying not about the use of spin but its inefficacy in selling his policies. This, Greenberg argues, is a more sophisticated view.

If employed for worthy ends, there is nothing wrong with spin as a vehicle for mobilizing popular support, Greenberg suggests. He traces our ambivalence on the subject to the ancient Greeks: While Plato denounced emotionally charged rhetoric, Aristotle countered that rhetoric was itself morally neutral, a tool that could be used for good or ill.

Rhetorical persuasion has always been part of politics, growing particularly fervent in times of war and heightened nationalism. (One thinks both of Winston Churchill’s rousing speeches to an embattled Britain and of the ugly, anti-Semitic propaganda deployed by Hitler and Goebbels.) But Greenberg, though he alludes to the Nazi propagandists, focuses on the United States, associating spin with an increasingly assertive presidency.

Theodore Roosevelt, “born for the spotlight,” is Greenberg’s Exhibit A. TR not only coined the now-ubiquitous expression “bully pulpit;” he held informal news conferences, hired press aides, and, when it suited him, collaborated closely with journalists to promote his favorite Progressive causes. (Doris Kearns Goodwin covered much of this territory in her 2013 volume, The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism.)

Woodrow Wilson, with his more academic and austere manner, had both successes and failures as a communicator. “He Kept Us Out of War,” from Wilson’s 1916 re-election effort, was one of the great presidential campaign slogans–but came to seem ironic, even deceptive, when America abandoned its neutrality just months later. Wilson’s innovative wartime Committee on Public Information, headed by onetime muckraker George Creel, was denounced by critics such as Walter Lippmann as overly propagandistic.

Greenberg notes that even the relatively quiescent Republican administrations of the 1920s used the techniques of the new PR and advertising gurus. Albert Lasker promoted Warren Harding using photographs of his handsome visage; Judson Welliver, a former White House reporter, became Harding’s speech writer, while somehow continuing to publish admiring magazine profiles of his new boss. Bruce Barton, an advertising pioneer, helped create “a wonderful [Calvin] Coolidge legend.” The New Republic’s Bruce Bliven duly charged that the candidate was being sold “as though he were a new breakfast food or fountain pen,” a strikingly contemporary plaint.

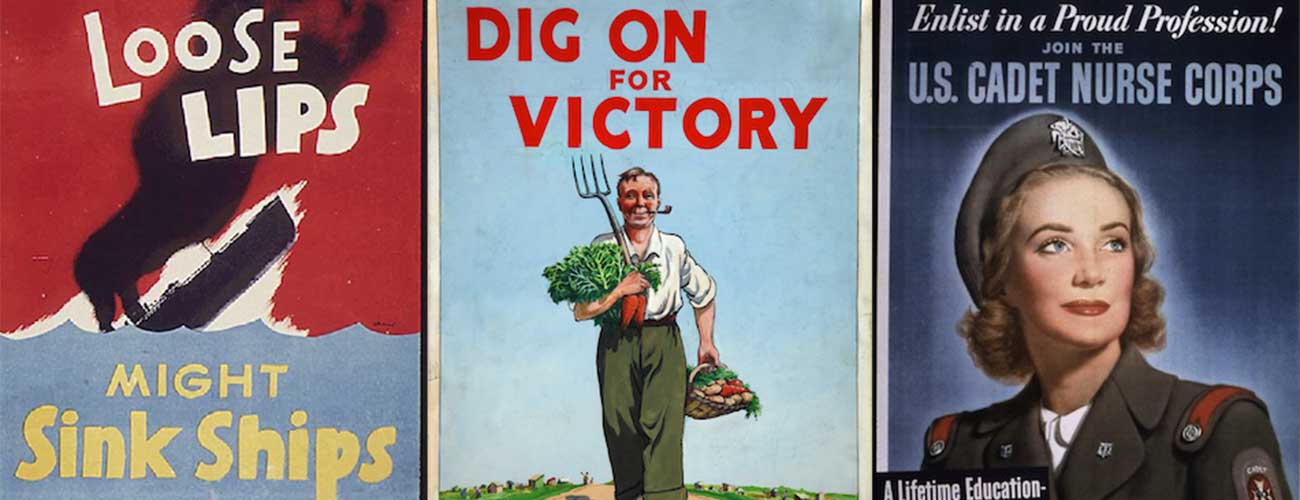

A political poster for Warren G. Harding in the 1920 presidential election campaign. (Library of Congress)

During this era, both Lippmann and the philosopher John Dewey worried about the ability of the press and the public to pierce the fog of public relations. Edward Bernays, known as the father of public relations, defended the nascent field, and Herbert Hoover sought his advice after the onset of the Great Depression. But, as Greenberg points out, even the best public relations couldn’t mask the country’s deepening economic woes; substance mattered, too.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, like his cousin, excelled at cultivating journalists, and his homey radio Fireside Chats were a high-water mark in the history of presidential PR. Professional political consultants and pollsters also appeared on the scene, including the now-forgotten, statistically rigorous but fallible Emil Hurja. During World War II, Roosevelt would tap the poet Archibald MacLeish to head the soon-to-be-controversial Office of Facts and Figures, whose name itself seems a propaganda triumph.

Neither Harry Truman nor Dwight Eisenhower was a PR innocent; at this point, no president could afford to be. His reputation for candor notwithstanding, Truman prepared rigorously for press conferences and radio addresses, and began to use television. He also unleashed Cold War-inspired psychological warfare. Eisenhower, old-fashioned as he was, aired the first television campaign ads. In the middle of the century, with the Cold War in full swing, cultural anxiety about “brainwashing” and the “dark power” of advertising crested.

And so we reach the Baby Boomer era, where the stories morph from history to memory: Nixon’s masterful “Checkers speech” and preoccupation with image; John F. Kennedy’s dominance of television; LBJ’s credibility gap; Jimmy Carter’s backfiring attempt to invoke a national “malaise,” Ronald Reagan’s gaffes and scripted eloquence, Clinton’s trial-by-pundit. This is recognizably our world, with its surfeit of handlers, polls, focus groups, and talking points.

Over the years, Greenberg suggests, the favored locutions for spin have changed. He organizes his book accordingly, describing the eras of “publicity,” “ballyhoo, “communication,” “news management,” and “image making” that evolved into our age of spin. He likes the current term, he says, for its “playfulness, irony, and even postmodern self-consciousness.” On a note of high optimism, he concludes: “[I]f spin is used for misleading, it’s also used for leading”–and to study it is to “see its long and deep connection to our politics.”

Greenberg’s deadlines no doubt precluded him from pondering the current presidential campaign, in which the dominance of non-politicians suggests new questions and concerns. Has rampant cynicism about both spin and our lumbering, unresponsive democracy put a new premium on embarrassing bluntness and insult? If policy detail is all but irrelevant and narcissism a selling point, how much does image making matter? And if nothing can be considered a gaffe, is there really any role left for spin?

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.