Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Earlier this month, North Korea declared it was drawing plans to launch four ballistic missiles near Guam, a part of the Marianas archipelago and an unincorporated territory of the United States. In the aftermath, US media coverage ramped up. Americans frantically Googled “Where (or what) is Guam?” and journalists rushed to explain the island’s unsettled relationship to the US and speculate about the impact of North Korea’s threat.

In the process, many news outlets displayed a troubling century-old pattern of their own: a fixation with Guam’s size.

Often starting from the headline, hundreds of articles in the mainstream press remarked on Guam’s proportions. It is “tiny,” “a small slice” and, even more dramatic, “a speck of earth.” On the surface, these depictions might be dismissed as simply a writing tic of journalists trying to say the word “small” in increasingly exotic ways. They may also be aimed at making Guam more interesting to American readers, most of whom have never heard of the island despite it being a US territory since 1898. But the matter goes deeper than that.

It’s not unreasonable to describe Guam—30 miles long and nine miles wide, with a total area of approximately 211 square miles—as a small island in specific contexts. Yet the frequency with which journalists unnecessarily repeat the idea suggests the description may have little to do with geography. Rather, to the extent that “size talk” tends to appear only when discussing Guam’s relationship to the US or the American military, its main effect is to render the island’s colonial subordination as natural and rational. In other terms, showering Guam with diminutives is not a tic—it reflects how US media sees Guam’s worth and purpose.

A Washington Post article by Anna Fifield, the newspaper’s Tokyo bureau chief, was emblematic. Titled “Some in Guam push for independence from U.S. as Marines prepare for buildup,” the piece includes at least 15 size-related words, and mentions Guam’s “small” physical or population size seven times.

Significantly, while “free association”—a form of independence that would cede core sovereign powers such as defense to the US—is defined neutrally, statehood and independence are described as potentially unviable due to Guam’s size. When considering Guam’s potential admission as a state of the union, Fifield affirms that Guam would be “a very small state… with a population less than one-third of Wyoming.” Even further, when referring to the possibility of Guam choosing independence, she asserts that this would turn the island into a “minuscule” state. The message appears to be that given its size, Guam’s desire to become a US state or an independent nation-state is ridiculous. Who can take a microstate seriously?

Equally important in this and more recent coverage, Guam is not the only player portrayed in terms of its proportions; so is the US military. Predictably, if Guam is small, the military is “large,” “outsized,” and just “huge.” In Fifield’s words: the island houses a “huge air force base” and is experiencing a “huge military buildup.”

Certainly, the fact that US armed forces own and occupy a third of the island is a fundamental part of Guam’s story and political predicament. But this “hugeness” is not deeply interrogated by the press or acknowledged as a structural, colonial inequity. If conflicts are noted, their reality and impact are generally accepted as part of a normal and ultimately beneficial relationship. In the words of Laura King from the Los Angeles Times: “Not unusually for a small, contained territory with a large military presence, there are occasional tensions between Guam’s civilian population and what can seem an overweening outside power. But the big U.S. deployment, together with tourism, is the island’s economic lifeline…”

Non-American English-language sources likewise report Guam differently, accentuating America’s peculiar vision.

Along similar lines, a widely circulated Associated Press report by Grace Garces Bordallo and Audrey McAvoy states: “The tiny U.S. territory of Guam feels a strong sense of patriotism and confidence in the American military, which has an enormous presence” even if “Guam has a sometimes complicated relationship with the U.S. mainland.” In these stories, the extreme militarization of Guam and its people is not treated as strange. What’s viewed as odd is that Guam is small.

Another way to see this trend is to compare how other “small” polities are described in US media. For example, the island state of Singapore is not much bigger than Guam, with a total area of 277.6 square miles. The Vatican, with an area of .2 square miles, is the smallest state in the world. Yet a review of articles published in top outlets like CNN, CNBC, The New York Times, and The Washington Post over the last two weeks reveals that neither Singapore nor the Vatican are ever reduced to size. On the contrary, most recent coverage relates to major political or financial questions, including the Vatican’s response to the support of some US Catholic leaders for Donald Trump and Singapore’s expanding economy and defense of its national interests.

Non-American English-language sources likewise report Guam differently, accentuating America’s peculiar vision. In an extended piece on the US military and the Pacific region, The Guardian consistently characterized the island in political terms: “a US territory in the western Pacific Ocean run by an elected governor.” Significantly, when the UK paper mentions the island’s dimension and population, it does not qualify them; in fact, the only descriptions that include size-related language concerns the military, which is said to have “a huge footprint.” One may argue this is the case because The Guardian is a left-leaning source often critical of US policy. Still, in an August 13 note on the possible impact of North Korea’s bombing threat on Guam’s tourism industry, the British tabloid Daily Mail offered an exoticizing word repeated in other articles but never mentioned size. It called Guam “a tropical island.”

The American tendency to insist on Guam’s smallness, however, is not new and encompasses more than land. Scholar Anne Hattori Perez has observed that Guam’s native people, the Chamorros, have also been described as “little.” At the beginning of the 20th century, for example, a group of white American women led by Susan Dyer, then-wife of the naval governor, sought to improve what they saw as “unsanitary living conditions” and replace indigenous healing practices with modern medicine. The group launched a campaign to build a hospital for Chamorro women, who as Hattori writes, “were referred to in the hospital’s fundraising campaign as ‘the little people of Guam.’”

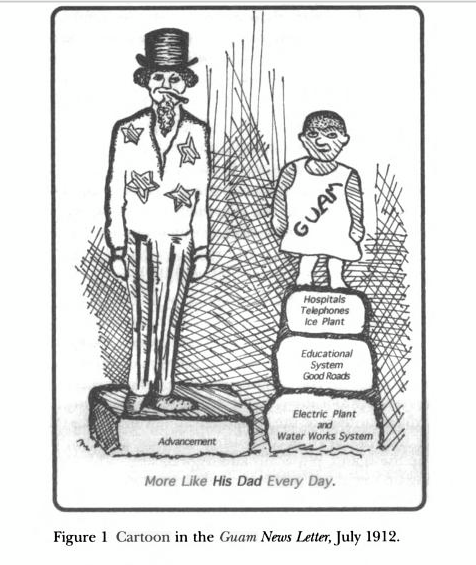

This persistent view of Chamorros as little and childlike was also crisply captured in a 1912 editorial cartoon published by the Navy newspaper Guam Recorder. The cartoon shows a roughly sketched Uncle Sam standing on a box labeled “advancement” next to a small dark-skinned Chamorro child standing on three boxes. Each box lists two or three of the “advances” brought by Uncle Sam to Guam, including “hospitals, telephones, ice plant, educational system, good roads, electric plant, and water works system.” The image’s caption is unequivocal in its paternalism: “More like his Dad Every Day.”

To insist on Guam’s smallness is a continuation of a colonial framework promoted by the military that still regards Chamorros as “simple and helpless people” in need of American protection, benevolence, and guardianship. The question of size, however, is not only relative—Guam is smaller than Hawaii but bigger than Barbados—and requires context to be meaningful: small or big for what purpose, and from whose point of view?

For some, what may be both disproportionate and untenable is the US political control of the island, its claim to a third of Guam’s land for military use, and a 120-year history of belittling. Guam’s demand for a non-colonial present remains undiminished. When it comes to a community’s right to freedom and justice, size does not matter.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.