Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

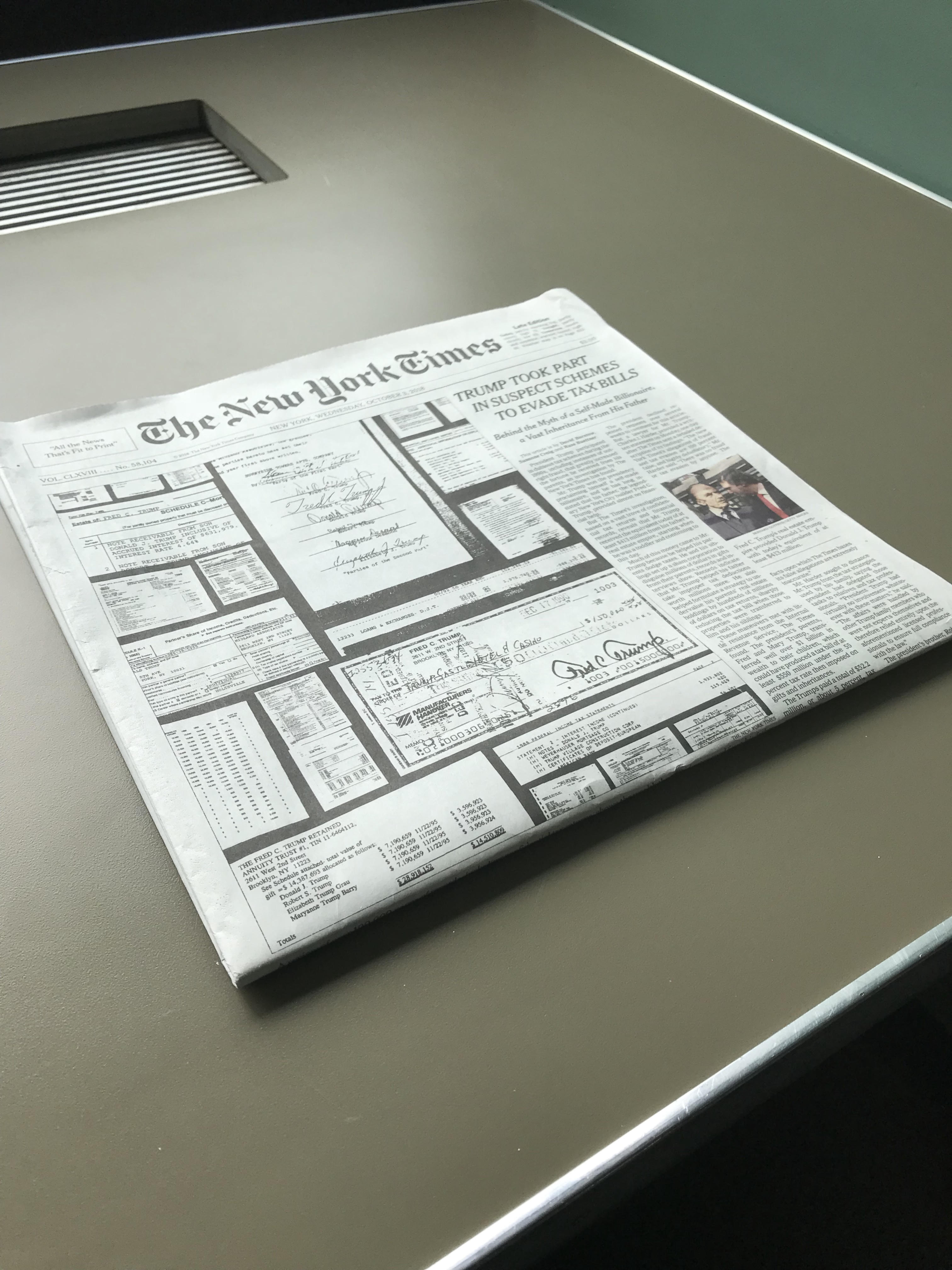

We live at a time when journalism can land with great force. The epic investigation published Tuesday by The New York Times, on the fraud that is the Trump family business, is such a story. The piece, which took three reporters—David Barstow, Susanne Craig, and Russ Buettner—18 months, 15,000 words, and eight pages in the print edition, has been roundly, and rightly, praised. One of its great benefits, to my mind, is that it transcends the headlines of the day, focusing on an elemental, fundamental aspect of this man and this presidency that, it turns out, is even more divorced from our common understanding than we might have previously thought. It is an example of journalism as long game, a sport that more of us need to be playing.

Told with a kind of sweeping and swaggering language that papers like the Times usually hold back; framed in an innovative way (essentially a biography of Fred Trump’s skeezy business practices); and impactful for its devastating conclusions, it removes any hold Trump still had on his claim of being a self-made business mastermind. This is, as described in one of my favorite facts from the story, a man who was funneled $200,000 a year by his father since the age of three. Yet he managed to piss it away, again and again.

RELATED: NYT and The New Yorker attacked for recent scoops

These are polarized times and the response to the Times piece reflected that. On the right, and among Trump’s team, the reaction was predictably dismissive and accusatory. Particularly rich, I thought, was a statement by Robert Trump, the president’s brother, issued on behalf of the entire family. It began, “Our dear father, Fred C. Trump, passed away in June 1999.” The statement went on to defend the family’s approach to business, which the Times summarized at the top of its story as “outright fraud.” Robert Trump concluded by pleading that the paper respect “the privacy of our deceased parents, may God rest their souls.” The implication, that it was untoward for the Times to delve into the business dealings of the deceased father of the president, was manipulative and offensive.

On the left, which has no love for Trump, the story was greeted with frustration. There was, for instance, the problem of the Times’ own role in elevating Trump as a Manhattan Midas—the paper had published the first of myriad fawning profiles taking his negotiating skills at face value. The Times, to its credit, acknowledged its mythmaking role in this story, and gave due to great reporters—including Wayne Barrett, Gwenda Blair, David Cay Johnston, and Tim O’Brien—who tackled the Trump family’s sketchy dealings earlier and more aggressively. (Such hat-tipping, employed frequently by David Fahrenthold of the Washington Post, is among the many journalistic upsides of the age of Trump.) Coming to terms with journalists’ complicity in the creation of Fake Trump—a role shared by almost every high-profile reporter working in New York City during the early 1980s—will be among the lasting legacies of this piece, even if it doesn’t heal all wounds.

There also were critiques of the paper from Trump haters wondering what took so long. Why couldn’t the Times have devoted resources to unmasking this man before he was elected to a position where he could do so much damage? Why was the paper of record obsessing about Hillary Clinton’s emails, which turned out to mean so little, when it should have been burrowing in on this, which means so much? The frustration is understandable, if ill-informed. Journalism is not an either-or enterprise—build a person up or take her down, at a time of maximum impact—because stories ebb and flow, sources come and go, reporters get pushed and pulled and reassigned.

The Times does still owe us a reckoning not only for its coverage of Clinton’s emails—which created a false equivalency between her misdeeds and Trump’s much worse offenses—but also for its dismissal of the threat posed by Russian election meddling. I, for one, don’t think journalism yet has its arms around the scale of that story, or its fundamental threat to the American system.

But so what? Do past failings mean that this week’s investigation should not have run? That, having missed one thread, the Times should have atoned for its sins some other way? (Perhaps here is where I should disclose that my wife is a reporter at the Times and that Susanne Craig, one of the reporters on the Trump business piece, is a former colleague of mine from The Wall Street Journal.)

I’ve been particularly irked over the last few hours by commenters who have waved the story away with a single dismissal: I knew that already. In fact, you didn’t know it. You thought it. You believed it. You intuited it. But that’s entirely different from having the raw information to back your theory up, to actually show, thanks to months of hard work, how it’s true and what it means. If, in assessing a story like this, you care little about its substance, you put yourself—however unwittingly—in the Trumpian worldview that facts don’t matter. And that’s not where any of us should want to be.

ICYMI: In Christine Blasey Ford’s opening statement, she had an important message for reporters

Kyle Pope was the editor in chief and publisher of the Columbia Journalism Review. He is now executive director of strategic initiatives at Covering Climate Now.