Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In early June, when Adamu Chan, a forty-one-year-old poet, dictated his verse over the phone from San Quentin, the coronavirus had already begun to spread through the prison. By the end of that month, San Quentin, which stands imposingly on the northern rim of the San Francisco Bay, became the second-largest hot spot for covid-19 in the United States. Chan was afraid. His unit remained relatively unaffected, but his friends—“my community,” he said—in other areas of the prison were rapidly coming down with the disease. To date, twenty-two people have died.

Chan read his poem, “Secret Ocean,” to Anastasia Sotiropoulos, his artistic partner on the outside, in successive fifteen-minute phone calls, interrupted by automated screening messages. The final version—sparse and emotionally intense, evoking isolation and longing—appeared in July, in a special issue of the Prison Renaissance Zine Project: “Incarceratedly Yours, covid-19 Issue.” It ends, “I see your footprints in the sand and anticipate our union.”

The Prison Renaissance Zine Project, a collaboration between the incarcerated artists of the Prison Renaissance collective and students at Stanford University, has been publishing since 2017. A summer issue wasn’t planned this year, until the virus began to explode inside prisons across the country; the group scrambled to produce an artistic response to the crisis. San Quentin has long had a thriving journalistic community, but in late March, fearing a surge in cases, administrators began a series of strict lockdowns, which closed the media center—a vital hub for the San Quentin News, the prison’s award-winning paper, as well as the zine makers. Journalists on the outside were barred, too; San Quentin became a black box. Chan and his colleagues, moved by a sense of reportorial responsibility, decided to work on the zine from their cells. “I feel strongly about my duty to speak out, because I know some people aren’t in the place where they can do that,” Chan said. He meant people with life sentences; he’s in for twenty years. “Your voice can get silenced and snuffed out here.”

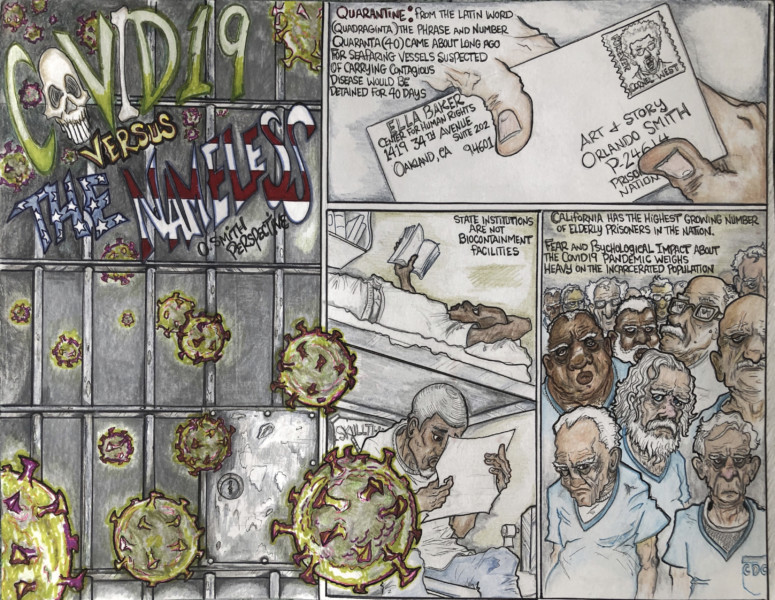

By Orlando Smith, for the Prison Renaissance Zine Project

Before the pandemic, incarcerated artists for the zine project often met with their partners in person. Vince Payne, a PhD student in chemistry, would make the two-hour drive north from Stanford’s campus, across the Golden Gate Bridge, to visit his artistic partner, Bruce Fowler, in San Quentin’s visitation area. Lately, since the two have been unable to see each other in person—and, for Fowler, even a trip to the phone can be impossible—they’ve resorted to sending letters back and forth. To design the zine’s cover, Payne used a screenprint Fowler had sent him by mail before the pandemic; they revised it over the phone when they could and through letters when that was the only option available. The final product shows a woman in red reclining in front of San Quentin’s fortresslike walls. It reads, in script that flows over a red sun, welcome to california: home of the pandemic of incarceration. (Fowler also made a sculpture, which was photographed for the zine: a small figurine of a man with bloodshot eyes wearing a gaudy yellow hazmat suit.)

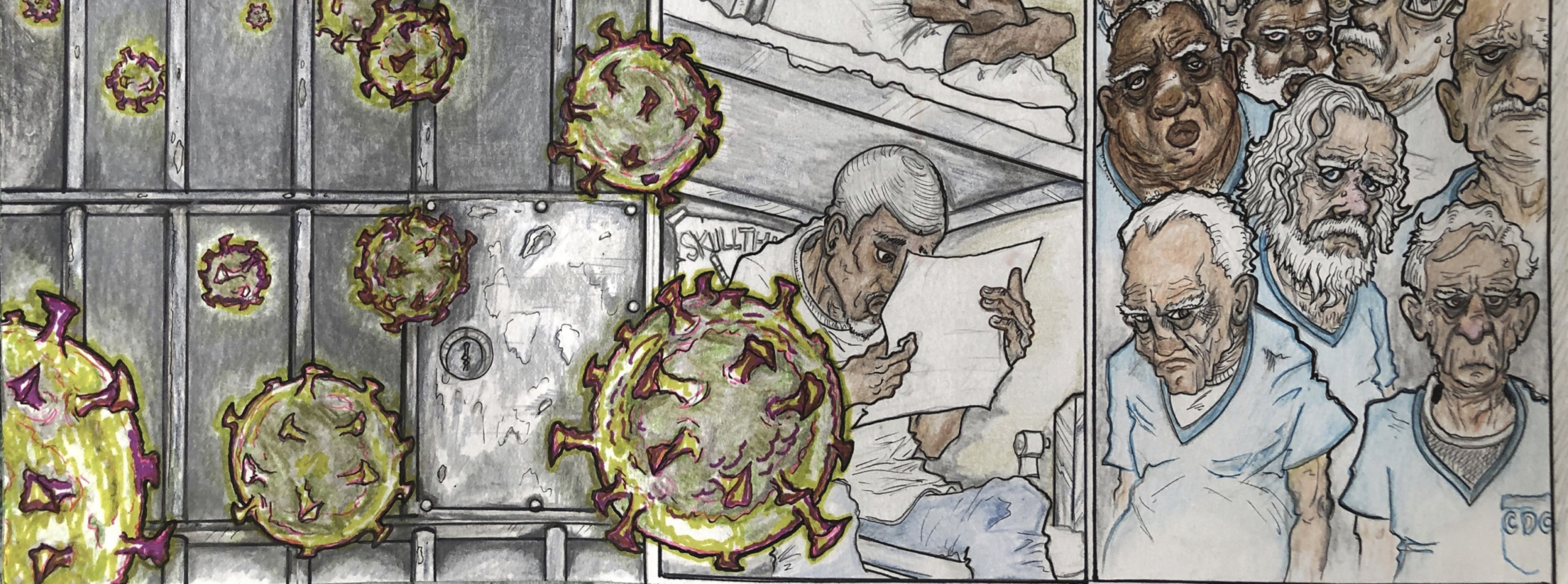

Another artist, Orlando Smith, contributed a vivid and disturbing multi-panel graphic story about life in San Quentin during the pandemic. “San Quentin has the highest growing number of elderly prisoners in the nation,” he wrote. “Fear and psychological impact of the covid-19 pandemic weighs heavy on the population.” Those words hover above a depiction of older men of various races, dressed in prison blues, their faces rendered in remarkable detail. The men look fearful, tired, and close to resignation; it’s a haunting image. The rest of the comic follows Smith throughout his day—the text is an internal monologue narrating the apathy of the guards and the austerity of the conditions. “I wanted to inform the world that California’s prisons are ill-prepared to deal with any fast spreading disease,” he writes in the last panel.

Chan wonders if that problem—the failure of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to confront the pandemic—has factored into the way officials have stifled reporting. “A lot of us are really involved in media,” he said. “We consider ourselves journalists. I think the fact that the worst outbreak in the state has happened here is really a nightmare for the Department of Corrections; there’s so much visibility in this particular prison.” He’s concerned, too, about the way outsiders might perceive the events on the ground. In the spring, Chan had hoped to participate in a symposium with invited guests from the New York Times, The Guardian, and other news outlets on how to sensitively cover imprisoned populations, but the event was canceled because of the coronavirus. Later, he followed mainstream pandemic coverage with some dismay (for instance, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a dehumanizing headline, “Condemned rapist, murderer of child dies in San Quentin”). The zine offers some media criticism; Smith’s cartoon spotlights the overly broad use of the word “lockdown” when applied to anyone not literally behind bars.

For Chan, the zine was an opportunity to cover the pandemic on his own terms—which meant, in part, experiencing a sense of connection to the artists and writers from whom he’d been separated while confined to a new unit, away from his original cohort. “A lot of people don’t realize there’s a community here,” he said. His poem was about missing his people not only on the outside, but on the inside as well. “The poem is also about being separated from my colleagues and my friends.”

RELATED: The hotline that helps detained immigrants share their stories

EDITOR’S NOTE: This piece has been updated to accurately reflect the conditions of Chan’s parole.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.