Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

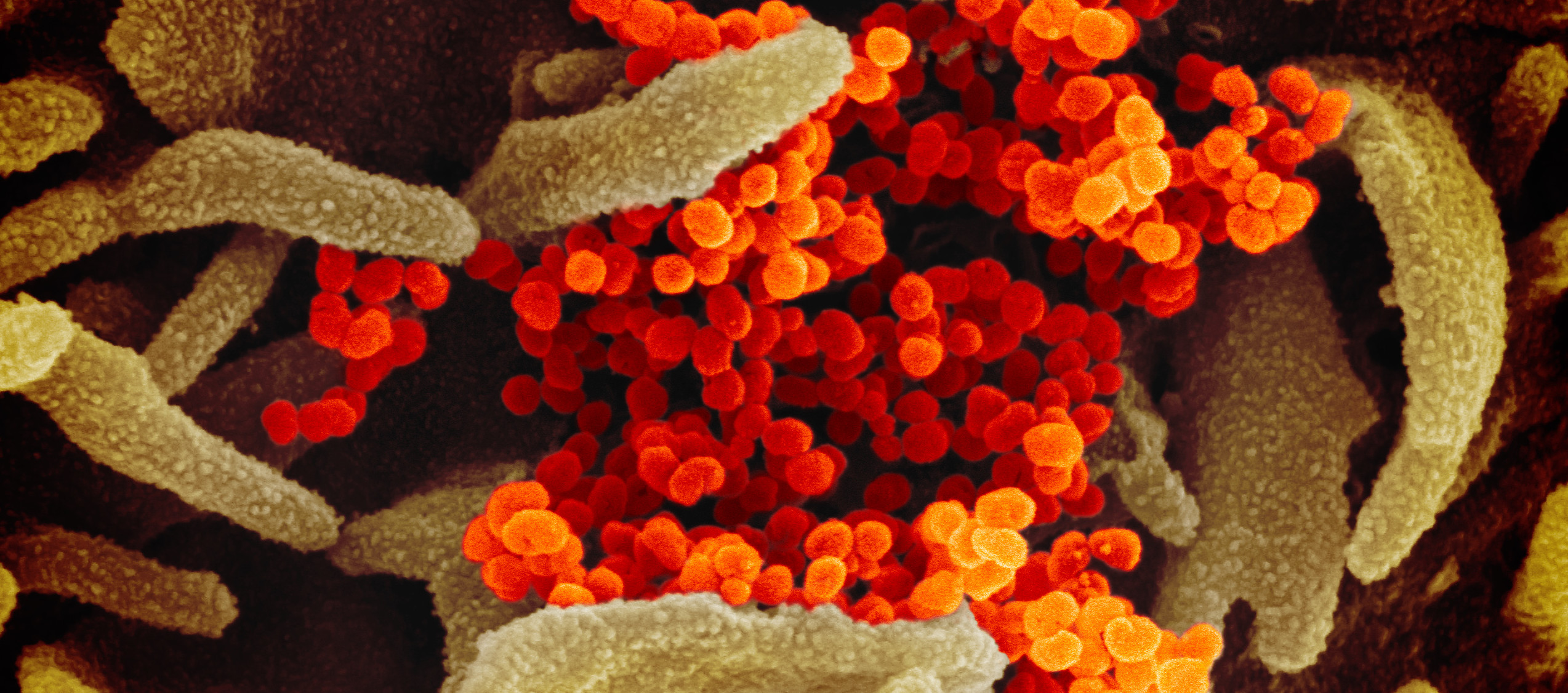

In January, when scientists in China released the genetic sequence of the novel coronavirus, researchers around the world began the race to develop a vaccine. The press followed along: Updates on tiny, incremental advances in the clinical trial process—largely sourced from preprints (unreviewed first drafts of scientific findings) and drugmakers’ press releases—were magnified as news alerts. Minor and expected setbacks in preliminary studies became major headlines, inciting alarm. As never before, journalists were tracking daily progress on research that typically takes years and is fussed over only by select quarters of academic medicine. The result has sometimes been distortion and whiplash. “Science evolves with the slow accretion of evidence,” Ellen Ruppel Shell, a professor of science journalism at Boston University, said. “But there’s tremendous competition to get that story out. And a lot of the coverage is almost done as if it’s a sports match: ‘Who’s going to be the winner?’ ”

Then came a pair of breakthroughs: in recent weeks, two vaccine front-runners—Pfizer and Moderna—announced promising early results thanks to their newly minted mRNA technology, which uses a synthetic version of coronavirus genetic material and has never before been approved for treatment in humans. Outlets covered the news with excitement; the stock market soared. A few reporters, though, realized that they needed to be careful about setting expectations. The latest developments are “a stepping-stone in a larger process,” Roxanne Khamsi, a freelance science writer and editor for Wired and other publications, said. News stories, she added, should always include what the next benchmark will be. “That in and of itself will tell people what to anticipate in the future and that this isn’t the end of the story,” she explained. “And it gives them a sense of when they’re going to hear the next chapter.”

For Pfizer and Moderna, the next chapter involves filing for emergency authorization from the Food and Drug Administration, which will scrutinize their vaccines for weeks. That means more data, for more kinds of test subjects—including seniors, whose immune systems are relatively weak, and who may dilute the efficacy rate, and children, who present another set of unknowns. Sarah Zhang, a staff writer at The Atlantic who has written on vaccines, antibody therapy, and end-of-life care, said that coverage should resist the urge to play up controversy over side effects. (We saw this recently when a coronavirus vaccine test volunteer in Brazil died during an Oxford-AstraZeneca trial; journalists blew up the news; later, it was reported that the man had been in the placebo group.) “Journalism has a tendency or bias toward what’s new and what’s unusual,” Zhang said. “So, in vaccines, a very unusual thing can happen in two people. And that is the news story. But it might be very, very rare, so it’s not necessarily relevant to most people.”

With any vaccine, Helen Branswell, a senior infectious-diseases reporter at STAT, said, there are limits to what lab research can reveal. We won’t fully understand the range of side effects until a drug is in wide use. (The mRNA vaccines have been tested in trials of about thirty thousand people; an adverse effect might not be found until the vaccine has gone out to, say, a hundred thousand.) Which, given the novelty of what went into the coronavirus vaccines, will get complicated. “These companies have never produced vaccines at commercial scale and tried to make a billion doses of something,” Branswell said. “So we’re in uncharted territory.”

Khamsi agreed. “It’s like you’re rooting for a person running a marathon and they’re hitting some really good mile times,” she said. “But they still have to run that frickin’ marathon.” Once the vaccines have been made, she’ll want to track how supplies are being allocated. “This has been a pandemic of inequities, and they will continue to the distribution model,” Khamsi said. “We get so caught up in the science. It doesn’t matter if there’s a 90 percent effective vaccine if only 30 percent of the population has access to it first based on their pocketbooks.”

Nor should journalists characterize vaccines as a “magic bullet solution,” Shell said, especially since much of the public won’t get vaccinated anytime soon. “We are beyond contact tracing; we almost don’t have an alternative to the vaccine,” she said. “But most vaccines don’t inoculate at a hundred percent, so you still have to have public health interventions.” Shell cautioned that an appearance of shoring up support—“cheerleading for the vaccine”—may inadvertently stir suspicion. “In the aggregate, the vaccine is of tremendous benefit,” she said, but coverage should say so “without downplaying or keeping negative events from the public.”

After the vaccines are sent out into the world, healthcare workers—the first recipients—will become crucial sources, as well as bulwarks against misinformation and doubt. Zhang intends to closely follow how they react to the new drugs. She’s also going to consider the full array of vaccines in development, not just the early leaders—speed, after all, isn’t the only measure of success; there may be more effective drugs still to come. Journalists, she said, should “talk about the covid vaccine not as one vaccine but a whole collection of different efforts that may have successes and failures.”

And when the outlook is unsure? “Be honest,” Zhang said. The story of the coronavirus vaccine cannot be rushed. “I guess I’m just trying to be like a weather report for the world,” she added. “Like: Here’s what’s actually happening. Here’s what we know might happen. But here’s the uncertainty.”

THE MEDIA TODAY: The good and bad news off the HuffFeed deal

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.