Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

CJR recently invited contributions from journalists whose work focuses on the healthcare challenges specific to their communities. We asked each reporter the same question: “As the nation anticipates passage of the Better Care Reconciliation Act, what are the health stories that are most urgent for journalists to tell in your region?” As the Senate moves towards a vote, we’ll publish more dispatches here, to encourage journalists to cover the changing health care landscape from the ground up.

IT’S NOT NEWS THAT KENTUCKY, West Virginia and Ohio are staggering under an epidemic of drug abuse. But the looming health threat of a related explosion of HIV infections is a story that needs to be told often, and loudly.

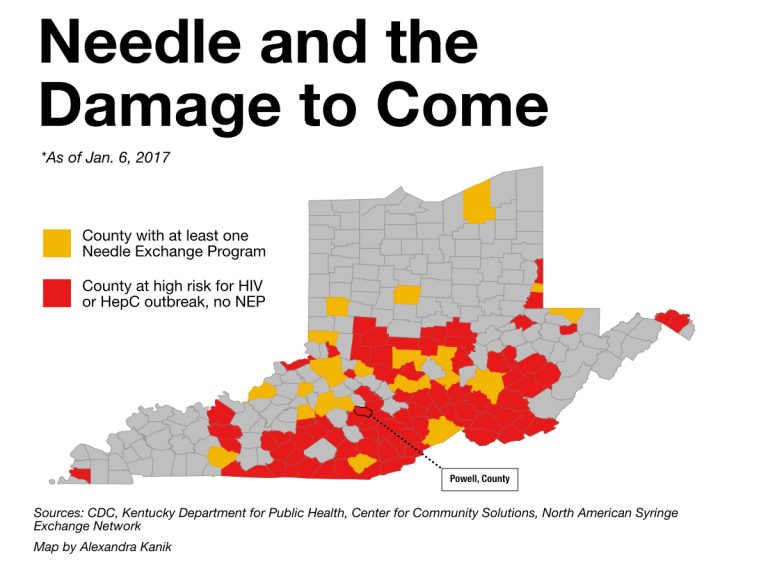

Nearly 100 counties in the three-state region are designated at high risk for HIV infection by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 10 counties that face the greatest risk are all in eastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia. On a map, those counties resemble a dark splotch in the heart of the country.

Courtesy of the Ohio Valley ReSource

The consequences of rural HIV outbreaks briefly reached the national media in 2015, when Austin, Indiana (population 4,200) started seeing dozens of HIV infections. News outlets including The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, Al Jazeera, and National Public Radio covered the situation in Austin, where 215 residents were ultimately diagnosed with HIV.

But, with few exceptions, the Austin story came and went. The risk of HIV from needle drug use continued to rise in rural places, such coverage declined, and federal funding for prevention focused on urban areas. (Laura Ungar of the Louisville Courier-Journal and USA Today recently published a three-part series on the ongoing issue.) In addition to providing thoughtful and thorough reporting, Unger’s stories demonstrate the importance of dedicated health reporters working outside of the nation’s media bubbles.

UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY RESEARCHER Jennifer Havens has studied a group of drug addicts in Hazard, Kentucky, since 2008. Havens’ work suggests HIV is likely to spread quickly within an interconnected community of rural addicts. Stigma about HIV could keep many from being tested, which increases the likelihood of further infections, and a lack of access to medical care would make HIV treatment difficult, predicted Havens. Intravenous drug use has already led to a spike in endocarditis, an infection of the heart valve that is often deadly and requires expensive and extended treatment.

There is hope. Public health officials consider needle exchange programs an effective and essential tool in preventing infections. Following the Indiana outbreak, state officials in Kentucky, West Virginia and Ohio made it possible for local health departments to create exchanges.

The struggle to combat HIV rates in my part of the country also represents a broader national evolution in how communities think of drug use.

As it has been put forward, the Better Care Reconciliation Act could significantly impact the Ohio Valley region, ravaged as it is by the opioid epidemic. That makes preventative measures such as needle exchange programs more critical. But needle exchanges require approval by local elected officials in culturally conservative communities, whose residents may view such programs as enabling users or encouraging more drug use.

IN MY REPORTING, I’VE SEEN civic-minded folks challenge their own biases for the good of their community.

Powell County, Kentucky, ranks 15th among American counties at high risk for HIV. Local officials recently voted to create a needle exchange program in Powell. For one story, I spoke with a nurse, a physician’s assistant and a pastor who first had to challenge their own religious convictions about drug use before supporting an exchange. In another county, residents were more likely to take condoms if they were discreetly tucked into small paper bags, rather than offered in a bowl. Such community-specific public health efforts make for important stories.

The struggle to combat HIV rates in my part of the country also represents a broader national evolution in how communities think of drug use. For a long time, drug use has been a law enforcement issue, not a public health issue. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy made news when he described substance abuse as “a chronic illness that must be treated with skill, urgency and compassion.

“The way we address this crisis,” said Murthy, “is a test for America.” That testing ground is Kentucky, West Virginia, and Ohio.

RELATED: Reporter posts front pages of LA Times, WashPo & NYTimes. Something was missing.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.