Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

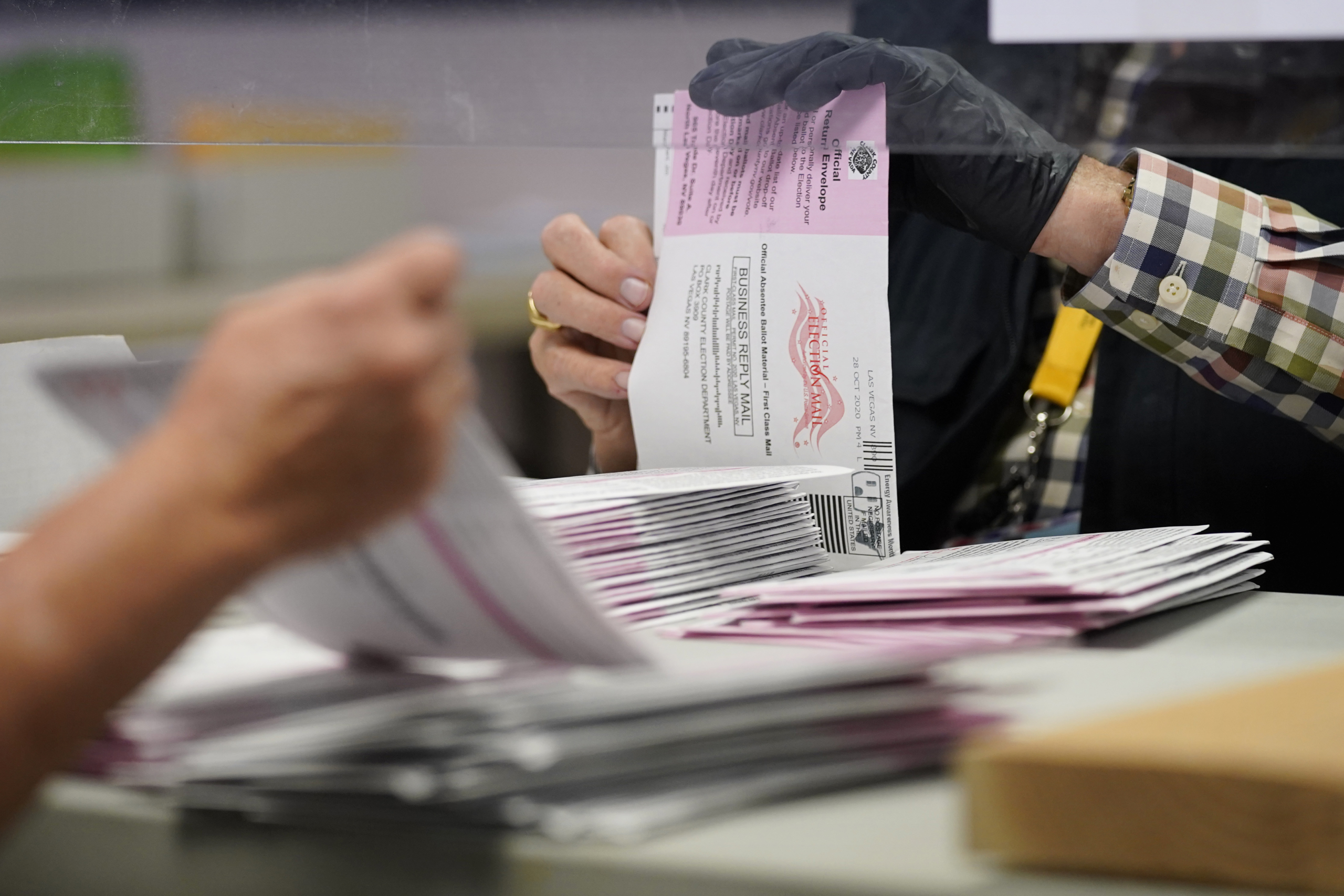

One week before Election Day, President Trump tweeted, “Big problems and discrepancies with Mail In Ballots all over the USA”—a claim he used to call for the dismissal of some of those ballots and for a definitive result on November 3 regardless of outstanding votes. Since the summer, Trump has cherry-picked examples of voting irregularities to paint a picture of an unreliable and exploitable system. Those examples are often plucked from developing stories covered by local news outlets that continue to pursue clarity for their readers even after the president reaches for the next one.

CJR spoke with reporters in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Georgia, Minnesota, and New Jersey about their efforts to reassure local readers about the integrity of the electoral process, even as national figures spun stories about their coverage areas. Most described their reporting on these issues as a balancing act—weighing the need to decisively counter Trump’s misleading claim against the possibility of appearing as a partisan corrective to a divisive president who has primed supporters to view journalism as dissent.

Paterson, New Jersey

On June 25, New Jersey’s attorney general announced voting fraud charges against four men in connection with a Paterson City Council election held the previous month. The election was the first one to be conducted almost entirely by mail, per an order issued by Gov. Phil Murphy in response to the covid-19 pandemic. The result was messy: nearly 20 percent of ballots were rejected, and multiple candidates contested the results. Trump latched on to the story, conflating the ballot rejection rate with instances of fraud. On June 28, Trump tweeted, “Bad things happen with Mail-Ins. Just look at Special Election in Patterson [sic], N.J. 19% of Ballots a FRAUD!”

Trump’s comments found their way into local and national coverage, including by Terrence T. McDonald, a reporter for NorthJersey.com. But critically, in his follow-up coverage, McDonald contextualized the number of ballots thrown out—just two years earlier, 11 percent of mail-in ballots had been rejected from a city election—and spoke with local officials and civic leaders who refuted the idea that the incident was predictive of what would occur in the general election. Many of the discounted ballots, McDonald reported, were actually discarded over issues with voters and deliverers failing to complete a “bearer certificate”—more likely attributable to error, not fraud. He also noted the Trump campaign’s lawsuit against the state’s new rules concerning mail-in ballots, which was ultimately thrown out; Trump’s repeated references to Paterson on Twitter; and Trump’s previous vilification of a New Jersey city in 2016, when, as a candidate for president, he claimed that “thousands and thousands of people were cheering” in Jersey City as the World Trade Center fell, an attempt to stoke anti-Muslim sentiment.

The few criminal charges that have been filed in relation to the Paterson episode are still pending—and, according to McDonald, are “so specific that it’s hard to replicate in anything other than a local race.” While McDonald allowed for the possibility that limited cases might demonstrate voter fraud, Trump’s comments, he tells CJR, “brought it to a different level.”

Atlanta, Georgia

On September 2, Trump instructed his supporters in North Carolina to vote once by mail and then again in person. One week later, Georgia secretary of state Brad Raffensperger revealed that some Georgia voters had apparently done just that, during the summer’s primary election, and announced an investigation. “We didn’t have a whole lot of information at first about who these double voters were or what their motivations may be,” Mark Niesse, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter who covered the state’s investigation, says.

Niesse had already covered the history of voter fraud allegations in Georgia, for a piece that called concerns over mailed ballots “more a fear than a reality” and offered examples of scenarios that, while technical instances of voter fraud, are not part of a nefarious or coordinated campaign. (“[W]hen it does happen, it’s small or unintentional: a mother voting for her daughter, election officials accepting several ballots without signatures, a woman who asked her friend to turn in a ballot.”) He built on that foundation for a new story, which made clear the lack of coordinated fraud: “Inquiry shows 1,000 Georgians may have voted twice, but no conspiracy.”

“There aren’t usually allegations of large-scale tampering with absentee balloting in Georgia, although everyone latches on to the cases they do hear about,” Niesse says. Many of the readers he has heard from during this campaign season believe that voter fraud is either rampant or nonexistent, rather than merely rare; readers who gravitate to one extreme are skeptical of those on the other, something Niesse attributes to coverage from national outlets as well as messaging from political organizations trying to drum up enthusiasm. The national fixation on voter fraud, he says, “makes me try to be as careful as I can. There’s no need to overemphasize what the news value of something is, because I think people are primed to pay attention.”

Outagamie County, Wisconsin

On September 21, deputies at the Outagamie County Sheriff’s Office in Wisconsin found three trays of mail in a ditch near Highway 96. A statement from the sheriff’s office said the mail contained “several” ballots, though many details, such as how many ballots were found or whether they had been completed or were being mailed to voters, remained unclear. Conservative outlets including Breitbart, Fox News, and the Washington Examiner ran stories about the incident, noting in headlines that absentee ballots were among the discarded mail. Trump appeared to reference the incident in the first presidential debate, during which he mentioned ballots found “in creeks.”

Patrick Marley, a state politics reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, has covered voting issues for more than a decade, including Wisconsin’s controversial 2011 voter identification law, challenges to which have sprawled into this election season. Given the gaps in the official announcement, he wanted to tread carefully. “You have the president stepping into that and saying—at least implying—it’s a sign of some kind of voter fraud effort,” Marley says. “And clearly a lost ballot is a problem, just like any lost mail is a problem. I wouldn’t say that amounts to fraud.” Marley held off on covering the story until October 1—the day the state elections commission announced that no Wisconsin ballots were among the discarded mail, a detail made front and center in the headline to Marley’s story. In the story itself, Marley put Trump’s claims in context, showing them against the backdrop of Trump’s previous assaults on mail-in voting and connecting mail issues to funding cuts and related slowdowns at the United States Postal Service.

Luzerne County, Pennsylvania

On September 24, the Department of Justice released a memo publicizing an investigation into the provenance of nine military ballots apparently discarded in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. The memo, which offered few details, initially noted that all the ballots had been votes for Trump, though that language was later corrected. The next morning, Trump referenced the episode in Pennsylvania, tweeting that “there is fraud being found all over the place.”

Within a day, Julia Hatmaker, a reporter for PennLive who covered the Justice Department announcement, had reported a more detailed account. The ballots had been accidentally discarded by a temporary worker who had been on the job for just a few days, and all had been recovered immediately. Hatmaker’s story emphasized that, in fact, the local election board’s processes were sound; its headline read, “Investigation over Trump ballots proves Pa. election system works: Luzerne County officials.”

Ron Southwick, managing producer and editor at PennLive, says his outlet is “not so much concerned with trying to look like we’re taking a side or that we’re out there trying to counter the message of the president. That’s not our job.” The headline to Hatmaker’s story did counter Trump’s message, but, according to Southwick, it was intended as a corrective to Trump’s allegations, which had already been amplified. “President Trump, with his extraordinary reach on social media, he’s able to get his message out quickly,” Southwick says, “and we wanted to make sure we were getting out what the local officials were saying in response to that message.”

Southwick says PennLive has adjusted its typical election coverage in an attempt to keep readers informed about the different ways they can vote, and how to ensure their votes are counted. Coverage this election season has frequently eschewed the more typical narrative stories in favor of concise information about the electoral process—how-tos, for instance, or maps of ballot drop box locations, even if it means republishing similar information. “We know people are really struggling to keep on top of everything they need to do just to get through the day,” Southwick says, referring to disruption caused by the pandemic. “So sometimes we sort of republish stories, with maybe a different headline, that’s just basic voter information.”

Minneapolis, Minnesota

On September 27, Project Veritas released a video that purported to show Rep. Ilhan Omar’s campaign paying people to collect ballots en masse from members of the Minneapolis Somali community and bring them to the polls. On its face, the video—which also made similar, vague allegations against Somali-American city council member Jamal Osman—raised many red flags: Project Veritas has a history of deceptively editing videos and passing them off as undercover journalism, and, at the time the video was likely filmed, ballot harvesting had been made legal by court order. The video was swiftly promoted by Donald Trump Jr. and went viral; an investigation by researchers with the Election Integrity Partnership later determined, per the New York Times, that the video was “probably part of a coordinated disinformation effort” intended to distract from a Times investigation of Trump’s taxes. Within twenty-four hours of the video’s release, Trump had retweeted a Breitbart story about it, writing, “This is totally illegal.”

After the video went viral, staff at the Sahan Journal—a nonprofit newsroom that covers news for immigrants and refugees in Minnesota, including the Somali community that the video focused on—discussed how best to cover it without repeating its central claims, many of which have since been widely debunked. Becky Dernbach and Hibah Ansari, Report for America corps members at the Sahan Journal, decided on a “truth sandwich” method when reporting on the disinformation, sticking false or misleading allegations between statements of fact to avoid amplifying the video’s disputed claims. To do otherwise, Dernbach says, would be to risk “perpetuat[ing] the sensationalism instead of getting at what’s true.”

The Sahan Journal’s relationship with the city’s Somali community, which helped elect Omar and Osman, also helped the reporters access sources that others missed. For example, they knew from their reporting that Omar Jamal, a central figure in the Veritas video, had a history as a provocateur and of making unverifiable claims. (Somali American TV, a Minnesota news show distributed via YouTube, was the first to note Jamal’s departure from the Veritas narrative—something the Sahan Journal flagged in its own subsequent coverage.) Some people depicted in the video, and others with knowledge of its making, came to the Sahan Journal with their stories. “I think that speaks to people hopefully trusting us with stories,” Dernbach says.

Mukhtar Ibrahim, the Sahan Journal’s founder, later posted a screenshot of Google results for the words “project veritas ballot harvesting.” The Sahan Journal’s explainer neared the top of the results—right after less critical coverage from Fox News and the New York Post. In his post, Ibrahim encouraged readers, “Keep reading and sharing our story.”

THE MEDIA TODAY: Getting election night right

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.