Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

EACH MONTH, Covering Climate Now speaks with different journalists about their experiences on the climate beat and their ideas for pushing our craft forward. This week, we spoke with Branko Brkic, editor in chief of South Africa’s Daily Maverick. We talked about “20Twenties: Eve of Destruction,” an adaptation of a Vietnam-era protest anthem, produced by Daily Maverick in order to call attention to the climate crisis. The conversation, with CCNow deputy director Andrew McCormick, has been edited for length and clarity. Follow Brkic on Twitter.

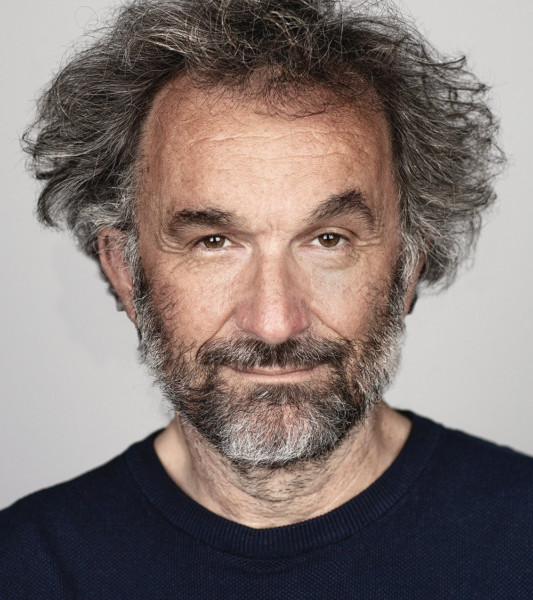

Branko Brkic, editor in chief of Daily Maverick. Photo courtesy of subject.

Can you share a bit about yourself and Daily Maverick?

I’ve been in the publishing business since 1984. I started as a book publisher in old Yugoslavia—I’m Serbian—and in 1991, amid Milošević’s civil war, I moved to South Africa. Starting in 1998, I founded a number of magazines, including Maverick Magazine in 2005, which I say was the beginning of “my Maverick life.” The idea was to be something of a cross between Vanity Fair, Fortune, and the UK’s Top Gear; we wanted journalism that was both interesting to read and beautiful to look at. But that collapsed in 2008, along with the entire global economy. In 2009, with my partner Styli Charalambous, I launched Daily Maverick, with the goal of bringing the same quality journalism into the online space.

At that time in South Africa, online journalism was still very much a cheap brother to print. But one man’s desert is another’s treasure. In 2012, after what came to be known as the Marikana massacre—in which thirty-four miners were shot dead—our investigations were able to prove that the killings were in fact murders by the police. This was a massive story that put Daily Maverick firmly in the country’s journalism picture. In 2017, we got hold of a hard drive and broke “the Gupta leaks,” which exposed major corruption in South Africa involving three Indian brothers who were buddies with then-president Jacob Zuma. These brothers were effectively choosing government ministers, getting all the government deals for their companies, and, in the process, becoming billionaires. The Guptas left South Africa soon after we started publishing, and Zuma resigned about eight months later. So, over time, I’d say we’ve been able to make a nice name for ourselves. In 2009, we had five employees and roughly twenty thousand readers. Today, we have one hundred twenty employees, two hundred contributors, and ten million readers a month.

Critically, everything we do is free to access, and we’re committed to keeping it that way. South Africa is a poor country, and we cannot afford for people not to read what’s going on. But the truth is expensive, and lies are cheap, so we tell our readers: “If you have the money, please help us.” We invite them to become part of our mission, appealing to the better angels of our readers who are better off, so that everyone in our audience can have access to quality journalism. And this has been successful. We have nearly twenty thousand subscribers, and our membership model is considered one of the best in the world.

When did the severity of the climate crisis sink in for you, and how did that affect Daily Maverick’s journalism?

It sank in a very long time ago, but, to be honest, I wasn’t sure what to do about it. For years, Daily Maverick was never more than a couple months from closing down. As a publication, when you’re just trying to survive, you don’t always have the time or energy to zoom out and think about the big picture.

“Day Zero” in 2018, when Cape Town was at risk of running out of potable water, brought the threat into much clearer focus—not just at the level of being rationally aware of climate change, but at the level of “Oh, crap, this is going to destroy our country.” We decided we had to do better, so Daily Maverick launched a climate unit, called Our Burning Planet, which today is staffed by ten people, full-time. I believe it’s one of the biggest climate units at any publication in the Southern Hemisphere. Mainstay issues for Our Burning Planet include water scarcity, biodiversity, and food security, in addition to regular climate news like the UN cop conferences. We also do a lot of work on Antarctica and have broken stories, for example, about Russia prospecting there for oil.

In the end, South Africa managed to get some relief in 2018, when rains came that fall and winter, and today our water reserves are doing better. But if you look at the climate problems that caused that crisis, you realize things are only getting worse. The west side of South Africa is getting progressively much drier and warmer. The east, separately, is getting wetter; earlier this year, catastrophic floods in KwaZulu-Natal killed some five hundred people. And yet we’re fighting serious issues of climate understanding in South Africa and a general malaise on climate that seems to have taken over the South African government. I have no doubt the water crisis will return to Cape Town in the coming years. What we are going to do then, I don’t know.

Much of Daily Maverick’s branding is about disrupting the status quo. Does your climate coverage fit in with that?

We’re lucky, because our journalists are true believers. For us, this is not just a job. It’s about trying to do something good, trying to help things change. In the four years since we launched Our Burning Planet, we’ve seen massive interest in our climate coverage, orders of magnitude greater than before.

Notably, all of our climate coverage is Creative Commons, so other outlets are welcome to republish it. We don’t see the climate space as one where we’re going to go out and make lots of money. Our goal is to make sure people understand.

In October, you launched “20Twenties: Eve of Destruction,” a song and music video about the climate crisis. What sparked this idea, and how did the song come about?

At Daily Maverick, we think, How many times are we as journalists going to do the same thing? The reality is that after decades of attempting to explain climate change to the world, a big chunk of the population still doesn’t believe in it, and many are quite aggressive, even violent, in their opposition to climate action. The point of the song, then, is: If we’re not succeeding by appealing to people’s rationality, let’s try to appeal to their emotions.

So one day, one of our journalists, Tiara Walters, WhatsApped me “Eve of Destruction,” a song that was a major part of the anti-war movement in the Vietnam era; in the US, it was the number one song in 1965. Tiara said, “Why don’t we adapt this and make it about the climate crisis?” In that moment, it was like a rocket had hit me. I immediately saw it. She and I sat together to rewrite the lyrics. The original, which was written by P.F. Sloan and sung by Barry McGuire, is already such a genius song—and the melody is so catchy—so, surprisingly, we only needed to change twelve lines.

Our goal is to show audiences what climate change means and what the catastrophe coming our way looks like. When you listen to it, when you watch the video, you can’t say, “I still don’t believe.”

The singer, Anneli Kamfer, conveys a lot of gravity with her voice but also a sense of hopefulness. Can you tell us a bit about her?

Anneli is such a big personality. She’s already quite a big star in South Africa, but we hope she’ll be able to catch on with a global audience. What’s very important: The 1965 song was sung by a white American, about American boys not wanting to go to war. This is a Black woman in South Africa singing about climate change; if you look at the entire planet, it’s the richest parts that are expected to suffer least, while Africa is expected to experience some of the worst effects of the climate crisis. So, for us, to have Anneli as an ambassador in this song is extremely important.

I was on a visit to Manhattan, between meetings, when I received her recording. I was on Park Avenue, and I stepped to the side to put in my headphones. I listened, and right away it was like BOOSH. I thought, “This is it.”

Who do you envision as your audience for this song?

Our target audience is global. Whether someone is watching this video in South Africa, China, or the US, we want them to see themselves in this video.

I’d say our two main targets, though, are young people and baby boomers. Young people because they’re the ones who will spend their life fighting through this. And baby boomers—my generation—because we’re the ones, whether we know it or not, who have played such a large part in this destruction. Today, my generation are world leaders, corporate executives, and prominent members of civil society. These are the people who, if we have any chance of survival, need to finally set aside their short-term ambitions. Some of these people might remember this song from a different time, when it meant something to them in their youth. When these people hear the song, applied to today’s crisis, I would hope they experience a sort of shame and then, more profoundly, a sense that we need to do something about climate change.

How has the reception been so far?

Sometimes you work on a project, and you’re so convinced it’s brilliant, but then you put it out into the world and people say, “So what?” I had to ask myself sometimes, “Are we crazy?”

But before launch, I played the draft video to over two hundred people, and more than half cried. Some cried at the dead fish. Some at the exploding coal. Some at the man in Bangladesh swimming in a pool of oil looking for metal scrap. In May, I took the draft video to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland; these are people who literally decide the future of the world, and even they were shedding tears in front of me. That’s not something you can easily fake. So I thought, “Okay, this is not just me smoking lots of illegal stuff.” Obviously, the song was connecting with people, including people on different continents, from different races, age groups, and classes.

After we launched, we felt the video was catching on, but then, suddenly, YouTube slapped it with an “eighteen and over” label, due to “scenes that will disturb people.” That removes the video from search results and makes it much harder to access. We complained, but the AI response we got back was “We hear you, but the decision stands.” We complained again and eventually managed to reach a human being, who lifted the label, but we’d already lost a lot of momentum, especially in the lead-up to November’s cop27 summit in Egypt. So now we’re trying to rebuild.

In a Daily Maverick press release, you described the song as the “finest example of music journalism” and discussed how journalism can take on different forms to achieve its mission. There are journalists out there who would be doctrinaire and say this isn’t journalism. What would you say to them, and why, for you, does this fall squarely in line with Daily Maverick’s mission?

There are many things that we learn to do when we’re young, and then we accept that way of doing things as a religion. I spent twenty-five years in print. Did the move into the online space mean abandoning my journalistic ethics and commitment to truth? Of course not.

The way I see this song is as a different journalistic medium or device. It’s a way of expressing the climate story without appearing to be another boring—because let’s face it, it’s often boring—or lecturing type of journalism. The subject of this story is: The climate is changing, the crisis is here now, we aren’t keeping up, and oh, by the way, the fabric of society is breaking down. You can write that story, but it’s going to be twenty thousand words, and no one’s going to read it. People have their daily lives. They need to take their kids to school, make a living, and make dinner. If we haven’t reached them on climate already, I’m not sure that asking them to read more is going to help. Yes, at Daily Maverick, we’ve published many stories about climate change, and we’ll continue doing so. But in this case, we managed to capture the whole of the climate story in just three minutes—and I’d argue it’s more effective than thousands of pages of reporting. The experience of the video is: “Holy crap, we’re in trouble.” People will understand that. And so, to me, this is a kind of journalism.

What are your longer-term goals for the song?

We’re pushing this song as a climate anthem. It was designed to be understood by everyone, so we’re hoping it can become a kind of binding glue to connect people across the world. In the coming years, we’d also like to do a global series of concerts. Nobody could say after Live Aid in 1985, “I didn’t know,” about the famine in East Africa.

More and more, as I grow older, the way I think the world works is that the best we can do is to create “butterfly moments”—you know the idea that a butterfly flapping its wings can eventually change the winds in a different part of the world—that might down the line help push humanity in a better direction. Throughout history, you find so many small moments that changed the world in unexpected ways—where the difference between big things going one way or another was very minuscule. The First World War, for example, wouldn’t have happened as it did if the Serbian guy who went to kill an Austrian guy had been unsuccessful, or if he was two minutes late. In my life, I want to provide good butterfly moments.

To do that, I think we need to break out of our mechanical processes. We need to try things that some people will find crazy or indecent or say, “Oh, that’s not journalism.” This way we can say, “At least we tried.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.