Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

“No! We’re not going back to the show, folks,” Jamie Simpson, an Ohio-based meteorologist, said on-air last month. Simpson had attracted criticism on social media after interrupting The Bachelorette to broadcast tornado warnings in late May, and decided to address dissatisfied viewers directly. “I’m sick and tired of people complaining about this,” he said. “Our job here is to keep people safe and that’s what we’re going to do,” he added.

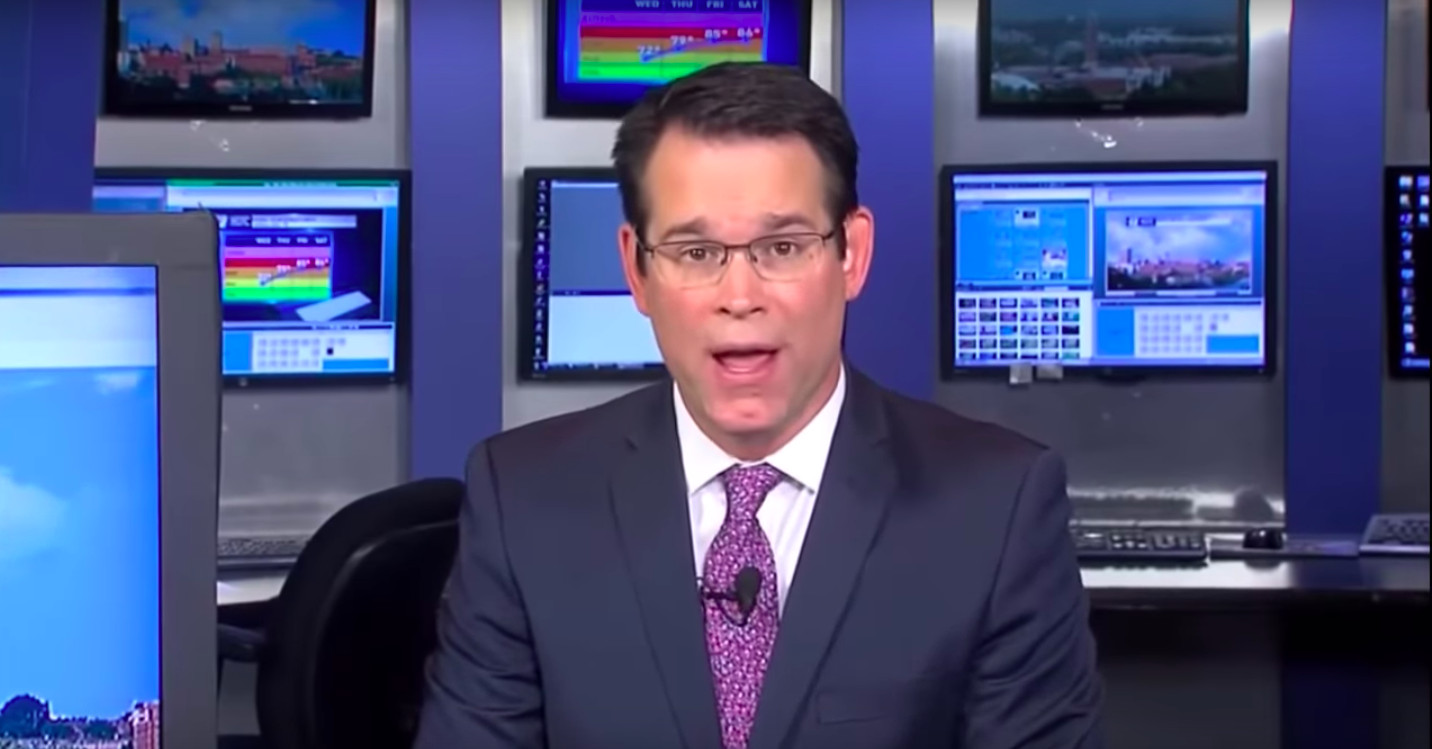

Also in May, as storms ripped through Virginia, meteorologist George Flickinger of Lynchburg’s WSET interrupted his station’s broadcast of Game Seven of the NBA’s Western Conference semi-final series to a split screen to alert viewers to a tornado warning in the area. WSET’s severe-weather policy required that Flickinger stay on-air for the duration of the warning—in this case, roughly 30 minutes. One male viewer called in to accuse Flickinger of “absolutely ruining Game Seven of Denver versus Portland.” Another male viewer told the station, “This is BS. You guys are terrible at your job.” Flickinger, during a segment explaining the station’s policy, said the station would not apologize for intruding on the game.

“Whenever there’s a tornado warning, lives are at risk,” Flickinger said. “You never know when someone new is tuning in, looking for critical information to protect themselves and their families.”

ICYMI: Climate reporters weigh coverage quantity against quality

Flickinger and Simpson are hardly alone. Television is the avenue through which most people find out about severe weather, and the FCC requires stations to broadcast local emergency information to all viewers. In 2018, Dustin Bonk, then a meteorologist at the Lansing-based WILX, interrupted a college football game for severe thunderstorm and tornado warnings, earning the ire of some viewers. In April, a Kansas-based meteorologist turned to Twitter to push back against viewers who criticized her for interrupting sports coverage for a severe weather alert.

https://twitter.com/CatTaylorKAKE/status/1122643143097237504

Debbie Petersmark, the vice president and general manager of Lansing’s WILX Media, supported Bonk’s decision to interrupt a football game. “Our severe weather policy allows any of our meteorologists the discretion to interrupt programming based on their opinion of weather conditions and viewer safety,” Petersmark says. After Bonk’s 2018 incident, WILX changed its station policy to present weather warnings in a split-screen alongside other programming. With that lone exception, Petersmark says she wouldn’t have done anything different.“We did everything else right,” she says. “I feel like our policy right now is solid.”

Even if stations haven’t yet dealt with similar decisions, climate change is slated to change that.

“One of the most obvious—and dangerous—impacts of climate change is increases in severe weather,” Edward Maibach, director of the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, tells CJR in an email. “We will almost certainly be getting more severe weather alerts on TV, radio, and especially on our smartphones.”

According to Harold Brooks, a senior scientist at NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory, there’s enough scientific evidence to suggest that, while climate change is creating fewer days with tornadoes, it is leading to more tornadoes on those days. It also means an increase in variability of severe thunderstorms because the two features that contribute most to them in the US—the high, cold air off the Rockies, and the warm, low air off the Gulf of Mexico—are going to change in ways we can’t fully predict.

Once people realize we’re listening and are taking their comments into consideration, and in some cases just hearing them, it generally tends to diffuse the anger.

How should stations navigate the programming interruptions associated with the severe weather that we’ll continue to see? Petersmark has had success with directly replying to viewers’ emailed concerns. In response to the 2018 incident, she replied to roughly 400 emails, taking the opportunity to thank viewers and to apologize for the inconvenience. “Once people realize we’re listening and are taking their comments into consideration, and in some cases just hearing them, it generally tends to diffuse the anger,” Petersmark says of the critical messages she received from viewers, most of which came from those who were unaffected by the weather discussed in the interruption.

Social media also plays a central role in weather interruptions for both stations and viewers. In addition to giving viewers a public alternative to calling into a station to complain privately, social media “has heightened the communal experience of shows,” Kim Klockow, a research scientist and the leader of the Societal Impacts Group within the National Severe Storms Laboratory, says. A delay or interruption in programming, Klockow says, “can mean not only missing out on something you wanted to see, but something you wanted to share.”

On top of responsive measures, there are also preventative approaches meteorologists and their newsrooms can take to more effectively communicate about severe weather events and procedures before they happen.

“Communication during dangerous weather events should focus on who might be affected, what they can expect, and what they should do to protect themselves,” Maibach says. However, emergencies are not the only opportunity to educate non-affected viewers. “That kind of information should be provided routinely—especially information about what to do in [the] event of dangerous weather—so that people need not do too much thinking if they get caught up in a dangerous weather event.”’

Meteorologists are also uniquely positioned to communicate about climate change with their viewers. Bernadette Woods Placky, the chief meteorologist and director of Climate Matters—a resource dedicated to informing the public on climate change findings—says broadcast meteorologists are one of the most trusted sources when it comes to information about climate change.

“They’re often the only scientist the public ever sees or has an ongoing relationship with,” Woods Placky says. “Because they come back frequently, they can have messages tied to events when and where they matter most.” Rather than recommend a single best practice for meteorologists communicating about severe weather and climate change with viewers, Woods Placky believes they should instead find their own individual voice in the process. “They’re good at their job for a reason,” she says.

ARCHIVES: Covering climate change through an olive grower’s eyes

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.