Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

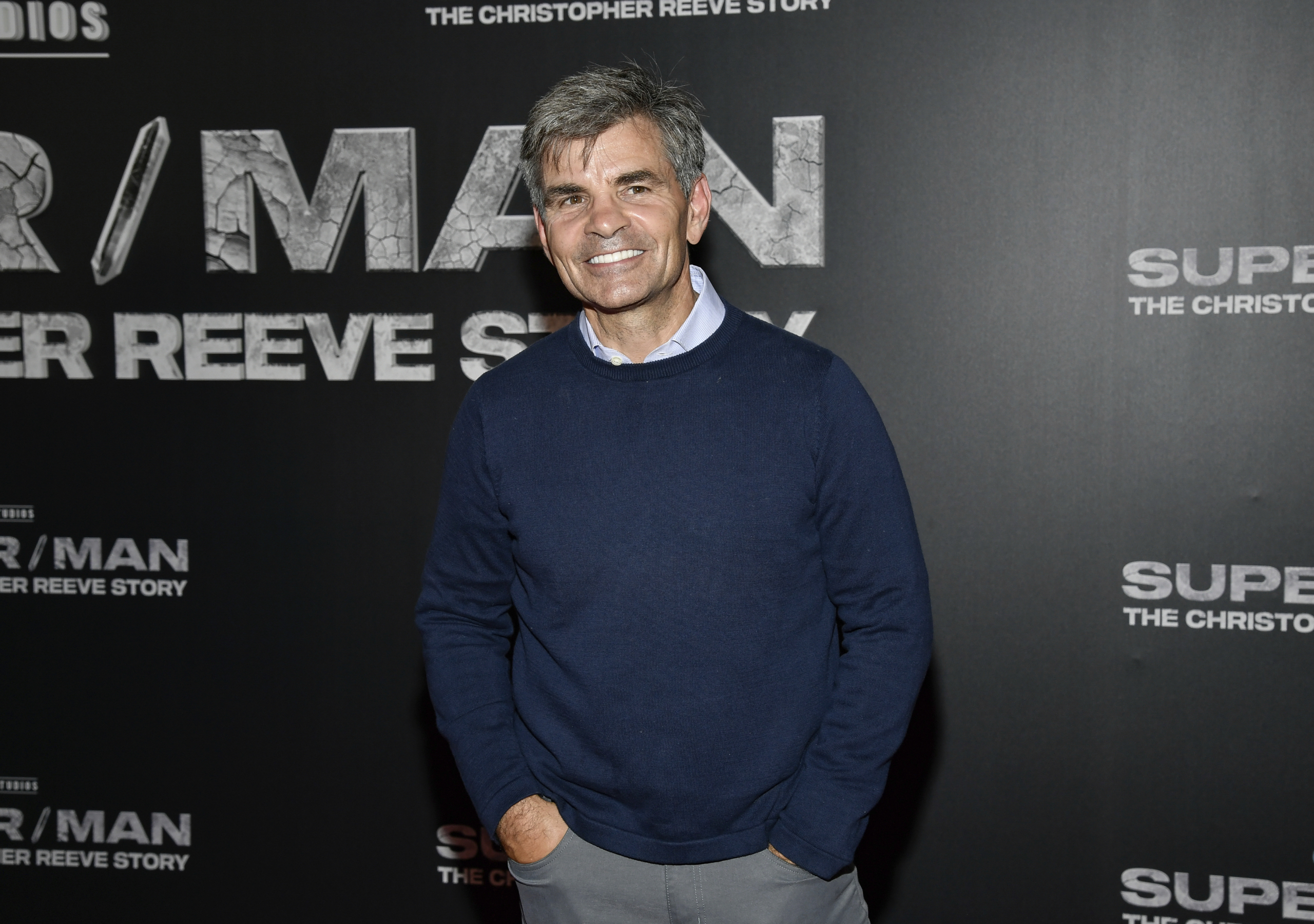

As someone who practiced press law for more than twenty years, and served as a senior executive of news organizations for just as long, I was shocked by the decision of ABC News last week to pay $16 million to settle Donald Trump’s libel case over George Stephanopoulos’s This Week broadcast in March. The shock came, and still lingers, because I—and every experienced press lawyer not involved in the case with whom I have discussed it—considered the case one in which ABC was likely to eventually prevail.

The decision to settle has been greeted by a lot of commentary, but almost no reporting of new facts. Understandably, that’s generated a good deal of hand-wringing about corporations “bending a knee” or gloating about the humbling of legacy media or an arrogant press getting its comeuppance. But such speculation does little to explain what happened.

In fact, only ABC knows why it settled the case, and the most important thing the rest of us can do right now is to pose the questions on which it owes us answers.

But before we do that, the necessary background:

In 2019, E. Jean Carroll alleged in an article in New York magazine’s The Cut that Donald Trump had raped her in the mid-1990s during an encounter at the Bergdorf Goodman store in Manhattan. Trump denied this then and has since, calling Carroll a liar. She sued him in 2019 for defamation and, when a new New York statute permitted it, in 2022 also for sexual assault. The latter case was tried before a Manhattan federal jury in April–May 2023, and resulted in an $88.3 million verdict in favor of Carroll. The only allegation of the complaint on which Trump won was the charge of literal “rape,” which New York law defines as vaginal penetration by a penis. Carroll had testified that Trump penetrated her with his finger. She prevailed on all her other allegations, of both sexual assault and defamation.

In refusing to set aside the verdict on a motion by Trump, the trial judge wrote in July 2023: “The finding that Ms. Carroll failed to prove that she was ‘raped’ within the meaning of the New York Penal Law does not mean that she failed to prove that Mr. Trump ‘raped’ her as many people commonly understand the word ‘rape.’ Indeed, as the evidence at trial recounted below makes clear, the jury found that Mr. Trump in fact did exactly that.”

On March 10, 2024, Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC), a survivor of rape, was interviewed by Stephanopoulos on ABC’s This Week. The interview lasted ten minutes, and more than seven minutes concerned the Carroll case.

The transcript of the interview reveals that it got off to a shaky start on what precisely happened in the Carroll case. Stephanopoulos first said “judges in two juries have found [Trump] liable for rape,” which is a bit of a word salad, and brought up a second civil case in which Carroll later prevailed on allegations only that Trump had defamed her in denying her charge.

But after the first few minutes, things got clearer. Stephanopoulos said nine separate times that Trump was “found liable for rape.” He also used the word “rape” three other times, more cryptically. Mace pointed out five times that this occurred in a civil rather than criminal case, and Stephanopoulos twice noted this as well. Finally, six-plus minutes into the contentious conversation, Stephanopoulos pulled up a Washington Post story reporting on the trial judge’s July 2023 opinion. Its headline, displayed for eight seconds: “Judge clarifies: Yes, Trump was found to have raped E. Jean Carroll.” Stephanopoulos’s paraphrase of this: the judge said Trump was “found to have committed rape.”

Trump promptly sued ABC and Stephanopoulos for libel in a federal court in his home state of Florida, one of many libel suits he has brought against the press over the years. Years after losing one of those cases—against Timothy L. O’Brien, then a New York Times business reporter and now the editor of Bloomberg Opinion—Trump told the Washington Post “in an interview that he knew he couldn’t win the suit but brought it anyway to make a point. ‘I spent a couple of bucks on legal fees, and they spent a whole lot more. I did it to make [the reporter’s] life miserable, which I’m happy about.’” While his wife, Melania Trump, once won a significant libel settlement from the Daily Mail, the current case is the only one against a media defendant of which I am aware in which Donald Trump either prevailed or settled for a cash payment. He has cases currently pending against CBS News and CNN, along with a suit against the board of the Pulitzer Prizes (which are administered by Columbia University).

ABC responded quickly to the Carroll rape libel suit by filing a motion to dismiss, a common tactic in such matters, but one that I and some others in the field have long considered overused. The upside of such a motion is that it can end a case quickly and relatively cheaply. The downside is that such motions, which require the judge to construe the allegations in the legal light most favorable to the plaintiff, can, if lost, make what’s called “law of the case” that can complicate matters as the litigation proceeds to and through the next phase, which is known as “discovery.”

In July, that’s just what happened to ABC. Judge Cecilia M. Altonaga, a George W. Bush appointee currently serving as the chief judge of the federal court in Miami, denied ABC’s motion, saying that a jury could—although it might well not—find that Stephanopoulos’s imprecise statements about rape were actionable, and that ABC’s additional proffered defense that Stephanopoulos had merely offered what is called a “fair report” of the Manhattan federal judge’s opinion was also unavailing.

I don’t find Judge Altonaga’s opinion persuasive, and I think appellate courts would likely have ultimately disagreed with her (as often happens when the press loses an initial motion in a libel case), but it’s not outrageous either. Notably, Judge Altonaga is reported as having tried to persuade her colleague, Judge Aileen M. Cannon, to stand aside in Trump’s criminal classified-documents case, which was dropped last month after he won election to a second term. She is no blind Trump loyalist.

With the July opinion from Altonaga, the case moved to discovery, including depositions of both Trump and Stephanopoulos. The court set a Christmas Eve deadline for ABC to file a motion for summary judgment, in which the evidence gathered in discovery is laid before the court to decide if there remains a factual dispute requiring a jury decision. ABC contended that the Trump side dragged its feet on discovery during the campaign, and last Friday a federal magistrate found for ABC and ordered the depositions to be held this week. The case was apparently settled the same day. In other words, ABC got what it said it wanted, and immediately, humiliatingly folded its hand, publicly saying that it and Stephanopoulos “regret statements regarding President Donald J. Trump made during” the Mace interview.

In the anticipated motion for summary judgment, ABC would have been entitled to argue that, even if Stephanopoulos was imprecise in his wording, it should still prevail without a trial on the legal issue of what is known as “actual malice.” The best definition of that was offered decades ago by the Supreme Court: it requires that Trump would have found in discovery some evidence that Stephanopoulos (or colleagues) had what it called “subjective awareness of probable falsity,” that is, that they knew that what they were saying was likely untrue.

That brings us to the questions ABC ought now to answer. (We posed these questions to ABC, which after repeated requests declined to comment on them.)

Did you learn, presumably after the motion to dismiss the case was rejected in July, of damaging evidence that might demonstrate actual malice? A positive response to this question would, in some sense (although not for ABC), be the happiest resolution of the mystery here. In a few libel cases over the years, “smoking guns” have emerged from newsroom files, casting doubt on the accuracy of stories before they were published. In such cases, settlement can make sense.

If not, didn’t you expect still to prevail on a motion for summary judgment? Absent such damaging evidence, ABC should have prevailed on a motion to end the case that it was scheduled to file just eleven days after it capitulated. Even if the network thought the judge might—again mistakenly—decide against it, and send the case to trial, well-funded newsrooms are not in the habit of paying millions to settle cases they may still win at trial, and are likely to on appeal.

Did ABC or Disney corporate play a decisive role in deciding to settle this case? This is the flip side of the “damning evidence” scenario, and the possibility many pundits have assumed, although again without evidence. One can imagine how Disney executives could conclude that a blow to ABC News, which accounts for less than 4 percent of Disney revenues, would make narrow economic sense at the advent of Trump II. From a societal point of view, this should be our greatest worry. If corporate executives who ultimately control newsrooms are going to surrender on stories that are substantially accurate, we are indeed in for a frightening period.

What dictated the timing of the settlement? It seems very likely that the answer was the forthcoming depositions of Trump and Stephanopoulos. Did ABC move because it wanted to shield one of its leading personalities from the revelation of evidence casting doubt on his or some colleague’s conduct? Or was the network motivated to save Trump the embarrassment of another rehearsal of the Carroll charges (which, again, the jury in the sexual assault case found persuasive)?

Have any ABC employees been disciplined with respect to this segment? If evidence of actual malice was found, you would think someone should have seen consequences for the interview making it to air in the way that it did.

If not, where’s the accountability for this blow to shareholders? Again conversely, if this was just a Disney short-term (and in my view shortsighted) dollars-and-sense decision, Disney execs may not want to take a bow, but it would be hard to punish the innocent. You might hope, though, that in such a case, a news veteran like Stephanopoulos would consider resigning in protest, of which there has been no sign.

Are you prepared to give any assurances that this does not represent a change in policy with respect to accountability coverage of those in power? This is the ultimate question, and why the whole matter deserves our time and attention.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.