Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

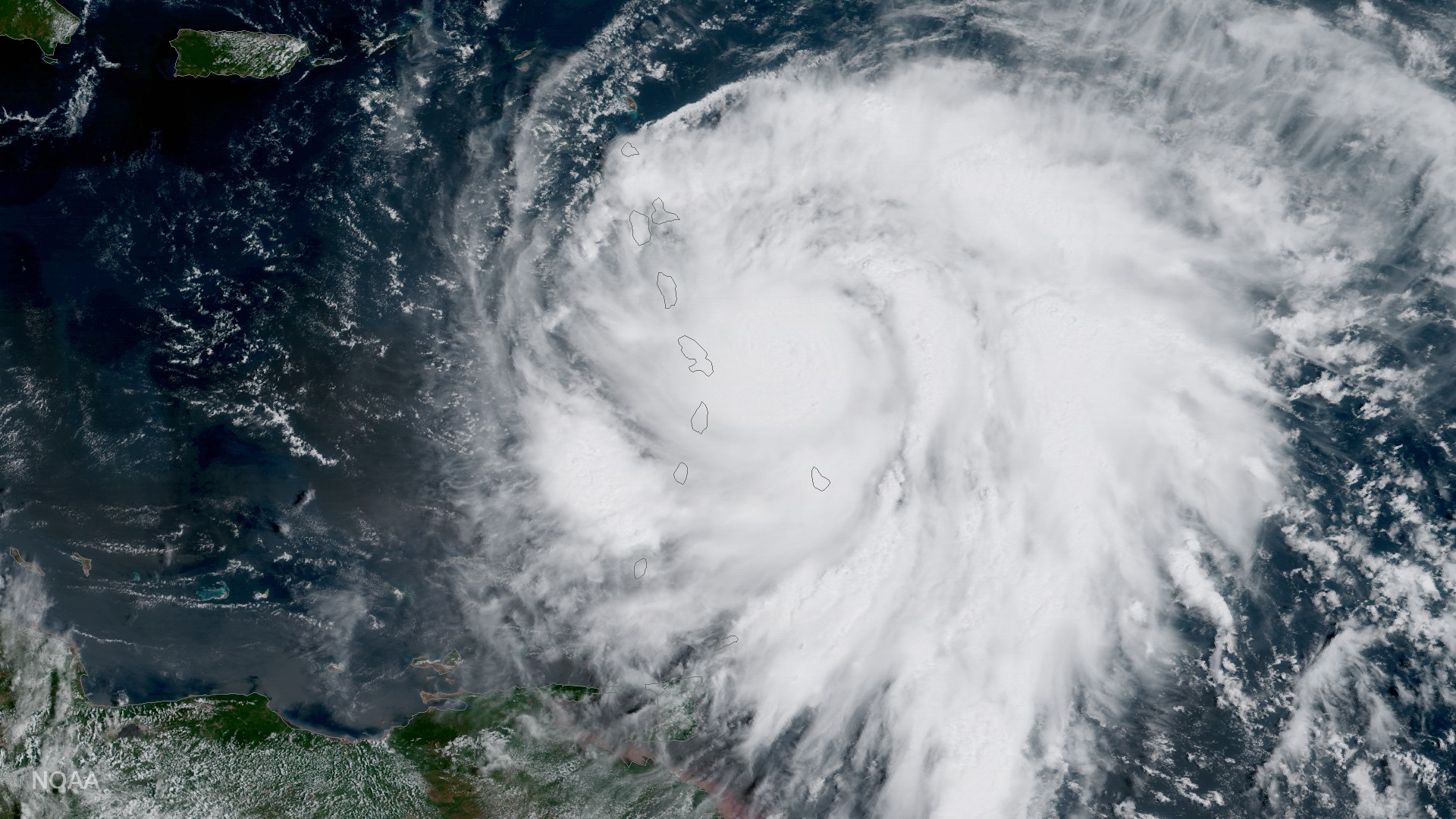

The staff of El Nuevo Día and Primera Hora, the two most important Spanish-language newspapers in Puerto Rico, felt their work had taken on a new sense of urgency after Hurricane Maria hit the island on September 20.

The island’s badly damaged electrical grid and limited cell phone service meant that the newspapers were the only ways for many Puerto Ricans to get their news. But just over a month after the hurricane hit, the staff learned on October 26 that 59 of their fellow employees (including 27 reporters, editors, and graphic designers) would not be coming back after a round of layoffs by Guaynabo-based GFR Media, the parent company of both newspapers. And rumors circulated that they wouldn’t be the last ones to go.

ICYMI: Headlines editors probably wish they could take back

Given the timing, the move infuriated journalists, says Manuel Rodríguez Banchs, an attorney for the union that represents them. “Print has been very important since the crisis,” he tells CJR. It’s clear that El Nuevo Día and Primera Hora have become a lifeline for Puerto Ricans: A company Facebook post had even bragged that the newspapers had managed to keep post-hurricane circulation near pre-hurricane levels of nearly 120,000 copies for El Nuevo Día and almost 68,900 for Primera Hora.

After the storm hit, the reporters scrambled to cover its aftermath, informing readers about the extent of damage, where to access medical assistance, how to apply for FEMA aid, and when to expect restoration of water and power. They acted as a conduit between elected officials, aid workers, and the public. Meantime, company executives were preparing to cut staff and employee benefits.

The company invited union representatives to a meeting on September 29. “We thought we were going to talk about ways to support our colleagues. But when we got to the meeting, they told us about their cash flow problems, and presented us with a list of their proposals,” Rodríguez says. “They were going to dismiss 50 percent of the staff. And they said they wouldn’t consider any other alternatives.”

The role of the newspaper in society is to inform and give voice. And increasingly, that role is under threat in Puerto Rico.

In a post on Facebook, GFR Media Board President María Eugenia Ferré Rangel says it was the union—not GFR—that was unwilling to negotiate terms. She added that given the reality of the island’s fiscal crisis, GFR had no choice but to let employees go. “Sincerely, we’re left with no other options,” she wrote.

When contacted by CJR by phone and email for additional comment, GFR referred questions to another El Nuevo Día executive, Farasch López Reyloz, who declined to elaborate.

ICYMI: Newspaper rocked by plagiarism scandal

Rodríguez wasn’t entirely surprised about the cuts; after all, he has played a key role in contract negotiations in the lead up to the December 31, 2017 expiration of unionized journalists’ collective bargaining agreement. The plan management proposed was consistent with actions GFR Media had been taking for years. “They eliminated the circulation department of El Nuevo Día in 2007,” he recounted, and earlier this year, in May and June, the company also eliminated staff. The papers together now employ 43 journalists, Rodríguez says. The staff cuts have come in waves, and the prospect of sudden unemployment is a cloud that hangs constantly over El Nuevo Día and Primera Hora staffers.

The journalists protested the staff cuts on Twitter, where they changed their bios to include the line “Bajo amenaza de despido” (“Under threat of dismissal”) and tweeted about GFR using the hashtag #AlguienTieneQueContarlo (#SomeoneHastoTellIt).

In addition to the staff cuts, GFR proposed cuts to employee benefits. Among them were proposals to eliminate the paid hour allowed each employee for lunch or dinner, to reduce the annual Christmas bonus to a sum that was the minimum required by law (2 percent of an employee’s salary, but not to exceed $600), and to reduce the number of vacation and sick days. In addition, GFR outlined a two-pronged plan for reducing remaining employees’ hours: imposing a mandatory four-week period of non-payment, as well as reducing shifts to six hours. To journalists, the terms seemed impossible.

As it was implementing its staff reduction plan, GFR was also throwing its weight behind a feel-good, post-hurricane campaign called “Unidos por Puerto Rico,” or “United for Puerto Rico,” which is accepting hurricane recovery and relief donations. “Millions of families have been affected by Hurricane Maria’s landfall in Puerto Rico,” a representative posted on the company Facebook account. “United, we can help our beloved island get back on its feet and become the country we all love…. Helping our neighbor, we help ourselves. We’re counting on you!” Journalists, other newspaper staff, and supporters took to Twitter to call the company out for what they viewed as a hypocritical stance.

RELATED: News outlet goes on lockdown ahead of Hurricane Irma

GFR, which is privately held, has seen its revenues fall, from about $180 million in 2014, to $170 million in 2015, according to the English-language newspaper Caribbean Business. But, as Rodríguez notes, GFR remains a profitable company. “There’s no doubt every business in Puerto Rico is going to lose revenues post-hurricane,” he adds, “but GFR admitted that its insurance will cover payroll expenses.”

While it makes staff cuts at its newspapers, GFR is expanding its real estate portfolio in the US and Latin America. In a statement to CJR, the company says the new division was in the works before the hurricane: “The launch of Kingbird Properties is a continuation of the diversification of Grupo Ferré Rangel’s portfolio that has been happening over the past decade. Grupo Ferré Rangel and the Ferré Rangel family remain wholly committed to Puerto Rico and its continued development.”

As the newspapers’ staffs are thinned, their ability to inform readers, both on the island and beyond, will be strained to capacity, Rodríguez says. And as more mainland US reporters pack up their notepads and cameras and return to New York newsrooms, leaving a sudden news vacuum, the role of Puerto Rican journalists to continue reporting on the ground will become even more important.

“The role of the newspaper in society,” says Rodríguez, “is to inform and give voice. And increasingly, that role is under threat in Puerto Rico.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.