Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

It was whispered like some secret oracle: Sidecat, sidecat is coming.

Negotiations over the tax incentive deal began in Ohio in early spring of last year, and only a cabal of quasi-state officials were in the know. Even after the $37.1 million in incentives were approved by state officials on July 31, 2017, the company was only referred to in a press release as Sidecat, a provider of “information technology services, such as remotely accessed computing power and data storage.”

RELATED: USA Today loses 5.8 million Facebook followers, and no one knows why

It wasn’t until nearly two weeks after the deal went through that The Columbus Dispatch uncovered that “Sidecat” was actually a code name for Facebook. After getting a tip from another reporter in the newsroom, Mark Williams, a business reporter, confirmed the information with anonymous sources, then went to officials at JobsOhio, the state’s privatized development entity, who wouldn’t confirm, either. “They were just continuing to wait,” Williams says. “At that point, you are shaking your head. What’s the big secret?”

Four days later, Ohio Governor John Kasich, at a symbolic groundbreaking in front of a banner bearing the Facebook logo, at last confirmed Sidecat’s true identity. Ironically, the deal to lure the social media giant to my home state of Ohio was hammered out earlier in the summer, as Kasich’s administration worked to plug a nearly $1 billion shortfall in the Rust Belt state’s budget. At the press conference in mid-August, flanked by dignitaries awkwardly holding shovels, Kasich hailed the deal as a step toward diversifying Ohio’s manufacturing-heavy economy with high-tech jobs.

But Facebook wouldn’t be coming to a struggling industrial region of Ohio, and it wasn’t guaranteeing many jobs. It was going to build a $750 million data center in one of the state’s wealthiest suburbs—New Albany, where the median household income is nearly $200,000 and unemployment hovers around 4 percent. Fifty new jobs were guaranteed.

The culture of secrecy, Williams says, makes informing the public about tax incentives before they are approved almost impossible. By the time of the groundbreaking, Facebook had successfully shielded itself from any public debate. It was too late for Ohio residents, or officials in more economically strapped regions desperate for jobs, to question whether Ohio should give a company worth nearly $500 billion massive tax breaks to locate in one of its most affluent communities. The deal was done. It had been hashed out over four months by JobsOhio, which conducts negotiations with companies like Facebook and Amazon entirely in secret. Although Ohio’s Tax Credit Authority must eventually approve deals, its role is largely ceremonial.

“For reporters used to covering public bodies, and used to contentious votes with lots of discussions back and forth…that’s not how it works with the Tax Credit Authority,” Williams explains. “They don’t say no on projects.”

Facebook sought to control the release of information, with a highly unusual demand: Officials must give Facebook at least three days before responding to any public records request.

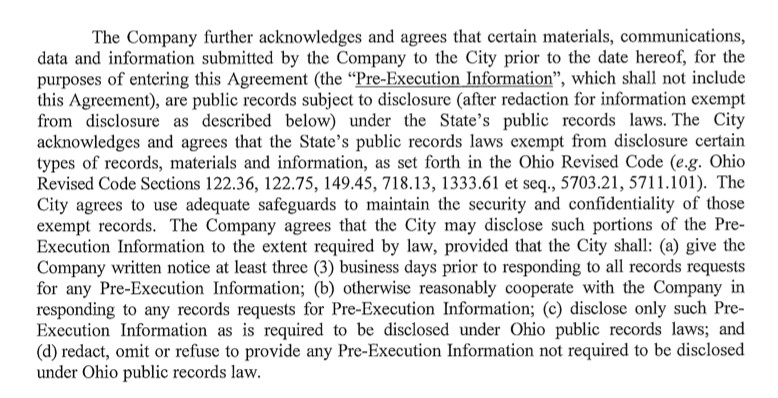

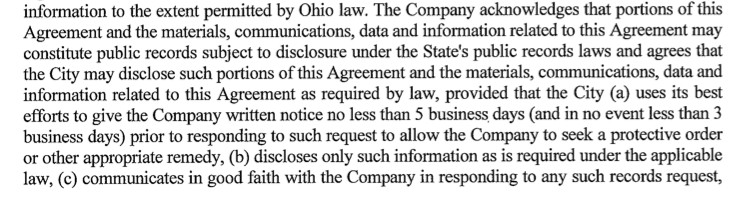

Of course, secrecy around tax incentives is no longer remarkable, especially in the handful of states—including Ohio, Rhode Island, Florida, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Arizona—where economic development has been privatized. But in this case, Facebook’s control over who could know what and when they could know it didn’t end there. In Facebook’s final agreement with New Albany, signed the day before Kasich’s press conference, the tech giant sought to further control the release of information, with a highly unusual demand: Officials must give Facebook at least three days before responding to any public records request. In other words, not until after the press conference would reporters get a chance to analyze the agreement. In the approved deal with Ohio’s Tax Credit Authority, Facebook also requests “prior notice” of any public records request, though it doesn’t dictate that notice in days, only demanding it be sufficient to “seek a protective order or other appropriate remedy.” Though Facebook is never directly identified in the agreement, the address listed, 1601 Willow Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025, is Facebook’s headquarters. (See excerpts below.)

An excerpt from the final agreement between New Albany and Sidecat, LLC, detailing the heads-up requirement for any public records request.

Such meddling into when and how a public body might release public records under the Freedom of Information Act represents an additional bureaucratic layer for reporters. “It’s always been about what government documents should be released to the public, but now we are seeing more of this shift to businesses controlling what documents governments can release to the public,” Williams say. Such control, in effect, allows companies like Facebook to stifle debate about the generous tax incentives they receive, at a time when a growing body of research says such giveaways don’t work—even as they drain public coffers to the tune of $45 billion a year, according to a report by the Upjohn Institute.

RELATED: Facebook is eating the world

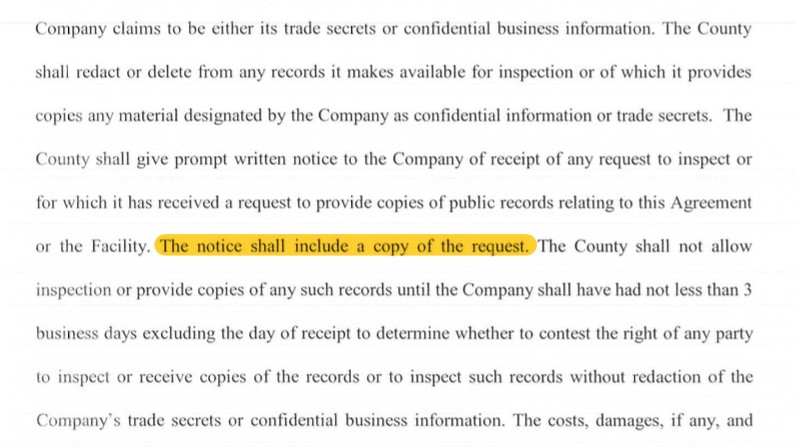

It wasn’t the first time I’d seen this odd demand by Facebook. I first noticed it in September 2017 while working on a story for Bloomberg Businessweek about a lucrative deal Facebook struck seven years earlier with a rural community in North Carolina. Not only did Facebook want to know at least four days in advance of any public records request being fulfilled, it demanded, “the notice shall include a copy of the request” (see below). In other words, Facebook would see my FOIA request before a public official could even respond to it. (While reporting this story, I shared this specific example with Facebook’s public relations team, but the company declined to comment.)

An excerpt from Facebook’s agreement in North Carolina in 2010.

John Cary Sims, a FOIA expert and professor of law at the University of the Pacific’s McGeorge School of Law in Sacramento, described the use of code names and FOIA request notices as a “trip wire,” or an “early warning system.” Facebook may also be trying to buy time to launch a “reverse” FOIA, in which a company goes to court to prevent a government agency from responding to a records request.

“It’s a game of muscle,” Sims says. “It’s very valuable to know at the earliest time what information someone has. It may also be about tracking what stories a journalist might be doing. It’s an ingenious way to try to get to the high ground, where they can assess the risk and apply pressure in a timely way so it comes out the way they want it to come out. It gives them leverage, and it may delay release for months.”

Facebook isn’t the only big tech firm stifling the FOIA process and obscuring public disclosure by shielding its identity with a code name of sorts. I’ve also found examples in Amazon agreements, which have won $1.2 billion in tax incentives from local and state governments as the company expands its footprint of data and fulfillment centers nationwide. For example, when Amazon negotiates to open a data center, it is rarely, if ever, identified directly as Amazon. Instead, the tech giant negotiates with local officials through its wholly owned subsidiary Vadata, Inc. This makes it difficult for local citizens to immediately know that Amazon, a company worth $656 billion, is the real beneficiary of such generous tax breaks. For example, in 2015, Amazon, through Vadata, struck an agreement with Hilliard, Ohio, for $5.4 million in tax incentives to build a data center in the working-class suburb of Central Ohio. But Amazon isn’t once identified in the documents I reviewed after my public records request.

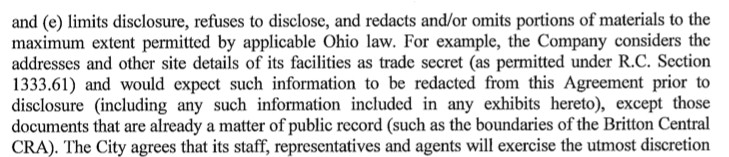

Additionally, Amazon, through Vadata, demanded a five-day notice before officials complied with any public records requests (see below). Amazon describes the notices as necessary to “seek a protective order or other appropriate remedy.” It also demands the city “limits disclosure, refuses to disclose, and redacts and/or omits portions of the material to the maximum extent permitted by applicable Ohio law.” In the agreement, Vadata demands site details and addresses of its facilities not be disclosed, referring to them as a “trade secret.” Amazon officials declined to comment for this story.

Excerpt from the 2015 agreement with Vadata.

“Hostile,” is how Greg Leroy, executive director of Good Jobs First, describes the emergence of such clauses, which his DC-based research policy group only occasionally sees firsthand. The group submits about a hundred FOIA requests annually to government entities as part of its ongoing efforts to track economic subsidies to corporations. “The idea that any private party would be told of a records request by a journalist made to a government entity violates everyone’s understanding about what is a public record,” he says. “It indicates that the public office is averse to disclosure, and is trying to help the private party either brace for the disclosure, or be strategic in how or what is disclosed.”

“The idea that any private party would be told of a records request by a journalist made to a government entity violates everyone’s understanding about what is a public record.”

Of course, corporate efforts to control closed-door dealmaking aren’t exactly new. In 2009, Aimee Edmondson, an associate professor at the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University, embarked on a 50-state analysis of state codes to understand how sunshine laws were restricted in the name of economic development. The study, titled “Prisoners of Private Industry: Economic Development and State Sunshine Laws,” found that at least 15 states had exemptions that closed all or part of such negotiations to the public. It’s not only meetings but records that are sometimes exempt from disclosure. For example, in Arkansas, the decision as to whether records related to a project are released to the public is left to the private company.

TRENDING: Texas Monthly EIC wades into an ethical gray zone

When I told Edmondson about the Facebook and Amazon “heads-up” requirements in recent agreements, she expressed concern. “I find that kind of clause very odd,” she says. “I think that’s a way for these big tech companies, who local officials are so busy courting, to take the temperature of the community and gauge whether there’s going to be pushback on projects. But it goes against the spirit of the sunshine laws. Clearly, they are concerned about media coverage and controlling press coverage. But anytime you have a situation where the only party that knows what is going on is the private company, there’s something fundamentally wrong.”

It’s not only within lucrative tax incentive deals that Amazon has sought to prevent public disclosure. Earlier this month, Ohio regulators approved a deal Amazon sought through its Vadata subsidiary, in private negotiations with the region’s largest public utility, American Electric Power. Amazon won a discount on its electricity costs, a significant cost for data center facilities, by threatening to take a massive expansion to another state. Amazon already operates three data centers in Ohio, and held out as a carrot plans to build 12 more. I asked JobsOhio if the state was offering additional tax credits to nail down the new data center construction. “That’s an easy answer,” spokesman Matt Englehart says. “That’s proprietary.”

If Amazon goes forward with such a massive building boom, it could become the single-biggest customer for American Electric Power in Ohio, potentially giving it enormous leverage to extract price concessions. But everyday retail customers of AEP might never be informed that their electric bills inched higher because of Amazon’s deal. That’s because only Amazon, AEP, and commissioners on the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, which is stacked with Kasich appointees and former industry players, know the exact details of the discount. Amazon claims such information is a “trade secret.”

Meanwhile, Amazon’s employment base in Ohio has grown to more than 6,000, but it hasn’t ushered in an era of shared prosperity. One in 10 Amazon workers in Ohio are receiving benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, according to a recent report by Policy Matters Ohio. And instead of bringing economic revival, Amazon drives wages down by an average of 3 percent in cities and towns where it opens fulfillment centers, according to a recent analysis by The Economist. Despite this, billions in additional tax incentives are now on the line as Amazon’s hunt for a second corporate headquarters narrows to 20 cities, including Columbus.

The tech giant, in conference calls with officials in the remaining cities, has made it clear contenders must do a better job controlling what information the public knows. The second-round RFP must not be released. Site visits must not be public events. In short, the demand of public officials by Amazon is unequivocal: Keep our secrets or you’re out of the running.

ICYMI: The Wall Street Journal unleashes a bombshell report

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.