Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

There’s a story behind every ingredient that goes into our meals—each plant or animal we consume carries the weight of the place where it was raised, the way it was cultivated, the history of its breeding. And as climate change alters the very nature of our planetary ecology—threatening certain staples and delicacies and modifying how and where others are grown—the narratives behind those ingredients are likely to shift in radical and unpredictable ways. (A report just this week by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicted that absent serious reductions in planetary warming, climate crisis could lead to global food shortages by 2040.)

These granular food narratives, which are rarely told, often hide within larger stories: They’re in articles about the fate of honeybees; or about the ways warming has affected the reach of certain plants; or about the unsustainability of large-scale cattle ranching.

And although the story of what we eat is critical to understanding the day-to-day experience of our changing ecosystem, climate journalism often looks beyond food, and food journalism rarely gets at the issues behind the experience of the meal.

But could a meal itself be a form of journalism—one that could bridge the gap between these two storytelling genres?

It’s an esoteric question, admits Mark Hansen, the director of Columbia’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation, but one that he hopes to examine through a series of experiments centered on small group meals. “Around a dinner table, we’re accustomed to taking global and national issues and filtering them through our lived experiences,” Hansen says. And sharing a meal naturally invites conversation.

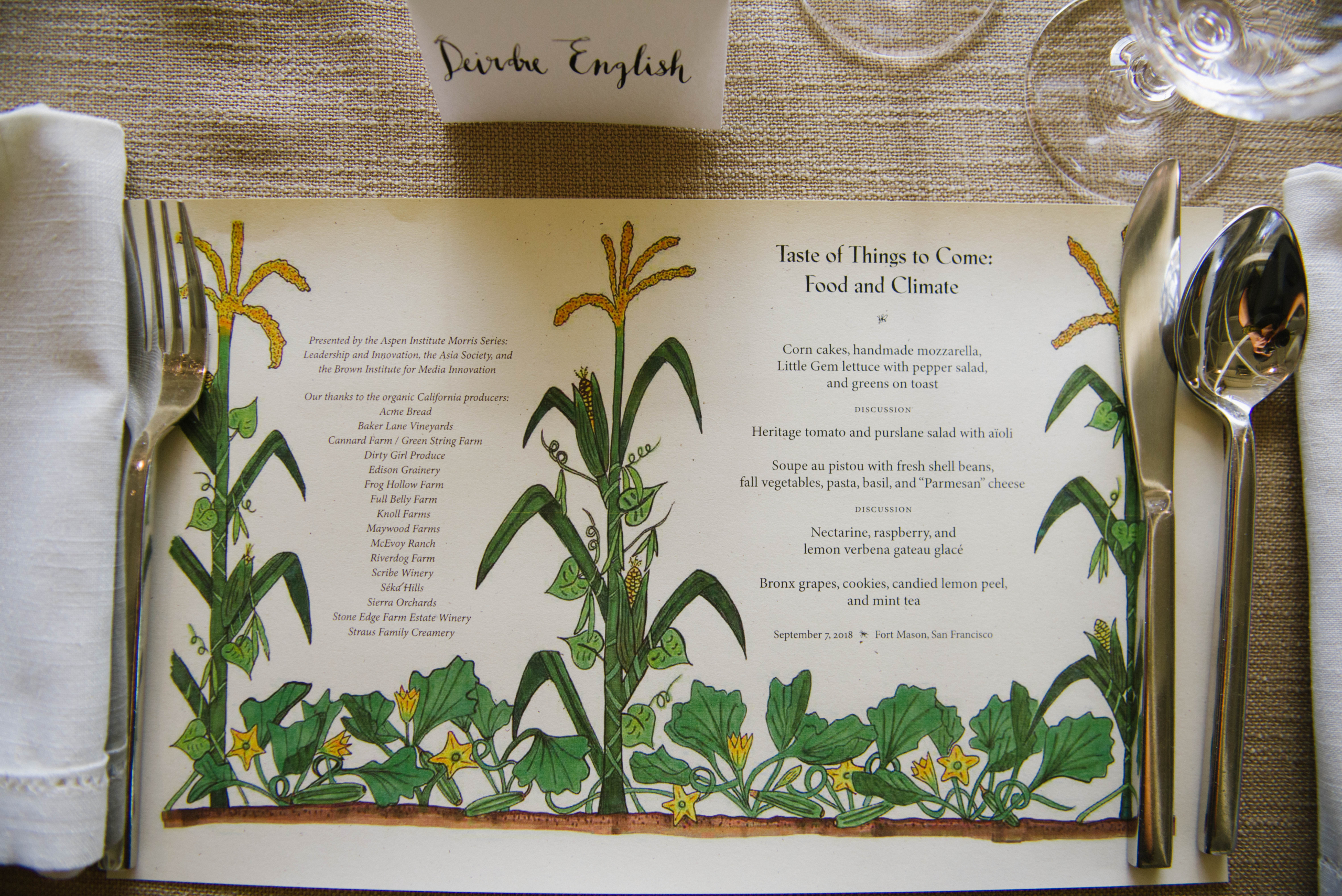

Hansen teamed up with legendary chef Alice Waters for a 70-person dinner in September at San Francisco’s Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture, a four-course meal prepared by Waters and her Berkeley-based organic food restaurant, Chez Panisse. The dinner was presented by the Aspen Institute as part of its Morris Series on Leadership and Innovation, the Asia Society, and the Brown Institute. In preparing the menu, Waters collaborated with Andrew Revkin, a science journalist at the National Geographic Society; Corby Kummer, a senior editor at The Atlantic and the editor in chief of IDEAS: The Magazine of the Aspen Institute; and Lisa Goddard, the director of Columbia’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society. Seated around the room, Kummer noted, were various “plants”: writers and experts on climate and food topics—such as New York Times climate change journalist Somini Sengupta, food writer Nathanael Johnson, and former Department of Energy assistant secretary Andy Karsner—who would spur conversation among their civilian tablemates. The goal was to create an experiential event that would show how food could be a backdrop for conversations about climate change.

“Media innovation is not just telling a better story,” said Revkin. “It’s having a better conversation, it’s building capacities using these great tools we have and knowing that you can do tons from the bottom up to spread better agriculture practice.”

The evening’s menu was itself intended to prompt conversation: The first item, a serving of corn cakes, contained millet, a heat-resistant grain likely to become more prevalent amid a warming climate. (“It’s the next quinoa,” Kummer quipped.) A salad included purslane, a common garden weed that also thrives in the heat. There were figs, which can grow almost anywhere, along with a plate of in-season, local California tomatoes. (“I find it utterly delicious,” said Waters, “to eat tomatoes at this moment in time.”) A bowl of soupe au pistou featured the “three sisters”—beans, winter squash, and corn—historically grown together in Native American traditions because of their mutually beneficial effect on the soil.

“Each course invites you to share your experiences of a changing climate, and to take up the often difficult social, political, and even cultural choices we are facing,” explains Hansen. “And because of this, each course is an experiment with a new kind of journalism, one that is tactile, tangible, and importantly, edible.”

So, with the dinner as a jumping-off point, Kummer led a panel discussion including Goddard, Revkin, Waters, and Stonyfield Farm cofounder Gary Hirshberg that touched on the limits of what climate science can predict, the most effective steps individuals can take to reduce their carbon footprints through food, and what role media innovation can play in changing how we talk and think about climate change.

Waters had insisted that the meal be meat-free, and the speakers agreed that adopting a reduced-meat diet would be better for the environment. “If there were 9 billion vegan monks,” Revkin said, noting that estimates suggest we’re heading toward a population on that scale by 2050, “they would have a very different carbon footprint than if there were 9 billion Las Vegas residents.”

But, he added, “there aren’t going to be 9 billion vegan monks in 2050. Meat is a part of most menus.” Still, he argued, it might be possible to find alternative production methods to reduce the negative environmental impacts of growing meat and the moral quandaries of slaughter—to create lab-grown or plant-based alternatives. “And to use less of everything: less meat all the time.”

Waters averred that we should start treating meat more like a “condiment,” an accompaniment to a whole-grain, plant-based diet centered on proper care of the land and a return to home-cooking. “We don’t know how to cook anymore in this country. No one cooks,” she lamented. And with consumers in search of cheap, fast food, she said, “it’s the person who’s growing the food that’s missing out. Or the person that’s delivering it is not being paid a living wage.”

As the meal progressed, and diners exchanged their tomatoes, purslane, and soup for a dessert of nectarine sherbet with raspberry and lemon verbena ice cream gâteau glacé—which was so quickly consumed that the event’s photographer didn’t manage to capture it—the conversation flowed between topics and speakers, taking up the themes and interests of each panelist.

Goddard cautioned against giving too much weight to headline-grabbing articles that claim to be able to predict the demise of specific crops, such as coffee or cacao. “I think there are a lot of things we can say with pretty good confidence about the risk of rising temperatures,” she said. “But whether or not we can answer this very specific question of when and where certain crops are going to become unsustainable, the science is not to that point.”

Goddard’s words echoed out over the clanking of dishes and the muted hum of table conversation into an airy corner of Fort Mason, a former U.S. Army post jutting into the San Francisco Bay, views of Alcatraz to the north and the Golden Gate Bridge to the west. The larger portion of the hangar-like center’s 50,000 square feet was taken up by Coal + Ice, a climate-change-themed photography exhibition curated by documentary photographer Susan Meiselas and exhibition designer Jeroen de Vries, which the evening’s diners toured before the meal.

As the discussion—and the meal—wound down, talk turned to hashtags and politics: Revkin mentioned #farmhack, a tag taken up by young farmers seeking new ways to take on an increasingly unpredictable industry, as well as a growing use of YouTube among farmers in India as a means to share strategies and stories within a country that has hundreds of spoken languages and dialects. “The basics of climate modeling haven’t changed in 40 years. It’s going to get warmer globally, [but] a lot of variations locally are unpredictable,” Revkin said. “In that environment you want agility, you want information, you want varieties of farmers to be able to talk to each other as efficiently as possible so bright ideas can move forward.”

Goddard, who had earlier proposed improving telecommunications to reduce the need for travel (she and the rest of the Columbia delegation had purchased carbon offsets to account for their cross-national trip to San Francisco) returned to the idea of changing our modes of communication: “[We need] to fashion our communication in a way that really starts to connect the climate thread and the climate opportunities with things that really matter to people—the economic bottom line, the health bottom line, and then what that means for our families and our own happiness.”

Hirshberg returned to the urgency of finding a way forward amid dire scientific projections and the apathy of political leaders. “One thing we do know about climate change from the earliest climate science is that we’re going to get hotter hots and colder colds,” he said, before diners filed out past Coal + Ice’s austere display, passing photos of people standing on flooded porches, shaky black-and-white footage of bare-chested men frantically shoveling coal, helicopter footage of sparsely snow-dusted peaks, and satellite displays of global weather patterns. “And we shouldn’t fool ourselves, it’s happening right now.”

The Brown Institute for Media Innovation is a collaboration between Columbia Journalism School and Stanford Engineering designed to encourage and support new endeavors in journalism and technology.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.