Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In 2019 the mayor of Worcester, Massachusetts, pronounced the local newspaper dead. “There is no real newspaper in the City of Worcester,” he said.

The Telegram & Gazette, which started in 1866, was not folding. It remains the largest employer of journalists in this midsize working-class city, known for its grit and its punk scene and for having invented the smiley face. It had, though, just dismissed its last columnist in another round of layoffs after a chain of acquisitions led the paper to be owned by Gannett.

When we think of national columnists, we think of breathless and endless takes—a bloated and exhausting corps of self-declared experts perpetuating tribal groupthink. But the opposite is true for local news. Local columnists usually started as reporters. They tend to know everyone, and have seen a large swath of local history firsthand. Maybe even made some. Their voices are informed, earned.

The news industry’s decline is marked as much by the loss of journalists like these as by newspapers. The country has lost a third of its newspapers since 2005 but two-thirds of its newspaper journalists—some forty-three thousand jobs. The majority of the cuts have come from the hundreds of regional daily newspapers owned by ten large conglomerates (of which Gannett is the largest).

The Telegram, for example, had some hundred and four staffers in 2005. Today, it employs just twenty. By December 2018, the paper no longer had an opinion page editor. Then they came for the columnists. Dianne Williamson was first to go, in 2018. In 2019, the paper laid off its last columnist, Clive McFarlane, the dismissal that led the mayor to declare that the paper was no longer “real.”

During their time, Williamson and McFarlane both regularly took on the sort of city-specific, niche issues that a national columnist couldn’t or wouldn’t. In order to capture the “talk of the town,” you need to be in the town, talking to people. McFarlane especially wrote about the city’s issues with race and class in a way that afflicted the comfortable and comforted the afflicted. He took to task the code of silence among police, covered racism and sexual assault in the public schools, and offered the occasional heartwarming slice-of-life story. It’s not the sort of stuff that gets you a CNN talking-head gig, but for a community’s understanding of itself, it’s invaluable.

Around the same time, Gatehouse, another conglomerate that would later merge with Gannett, purchased the Telegram opinion page’s main competitor, Worcester Magazine, where I was a columnist and one of four editorial staffers.

Within months, Gatehouse had cut the staff to one: me. I put out the magazine by myself for a miserable summer until it was restructured as a product of the Telegram’s already strapped features desk. For some forty years, WoMag had been a real, independently owned alt-weekly known as the Telegram’s small and scrappy competitor. Today, it’s a digital-only product of the competition.

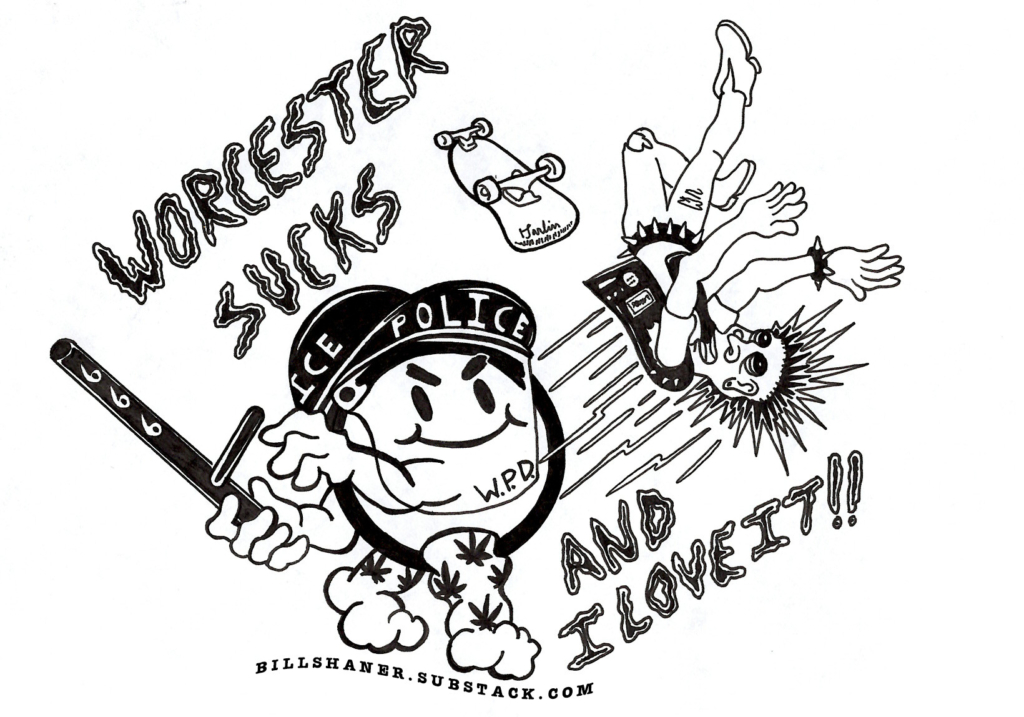

In June of 2020, after two of my columns were shelved without explanation, I, too, walked. The same day that I resigned I launched a Substack newsletter called Worcester Sucks & I Love It. It was a moment of desperation: either go independent or leave journalism entirely.

I had a strong sense that readers would follow me. I felt that fraught summer was a moment when an independent voice, willing to dig into issues like racism and policing, would find an audience. And it did. I hit four hundred paid subscribers in a month. Soon I had enough to match my Worcester Magazine salary. Now, at some 680 paid subscribers and a total mailing list of 3,650, the newsletter is my full-time job, and I’m in the process of parlaying it into a larger project: the Worcester Community Media Foundation, headquartered out of a small video rental store. There is a hunger for thoughtful opinion writing about local issues where so much of the content is thin.

The need I am fortunate to fill is not a need unique to Worcester. There’s been little written about the specific demise of the local columnist amid the grander decline of local news, but in their new book What Works in Community News, Dan Kennedy and Ellen Clegg dedicate a chapter to Pulitzer Prize–winning editorialist Art Cullen’s staunch commitment to opinion writing for his Iowa community. It’s a sentiment that resonates with me. Reliably, I get the strongest reader responses to my work in Worcester Sucks that takes to task the city’s handling of a growing unhoused population. In long essays blending opinion with policy review, analysis, and intimate portraits of specific unhoused people, I try to offer work that deepens understanding of an uncomfortable but important issue.

I’m aware that the years I spent at Worcester Magazine lent me the clout that made the newsletter launch successful. But it’s not work I could produce any longer within the constraints of a typical local reporting job. Certainly not in Worcester. The outlets that remain are either devoted to high volumes of short, timely stories, favoring those easily produced by harried reporters—press release rewrites, crime stories, short meeting recaps, and real estate listings. One, the Worcester Guardian, was launched by the local Chamber of Commerce and receives funding from key city power brokers. By contrast, my business model is very simple: I need to provide local journalism that people want enough to support directly. Reader trust is the currency, and I am blissfully unbothered by the typical considerations of content volume, “eyeballs,” and clicks.

It was likely those considerations that, at least in part, led the Telegram to get rid of its columnists. There is value in a local columnist’s role that doesn’t neatly translate to the spreadsheet. But the same thing goes for the loss of that value. Newspapers like the Telegram—and their readers—are finding that out the hard way.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.