Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

On March 3, 1977, PBS broadcast the familiar image of William F. Buckley, Jr. atop a small dais. His guests—Eduardo Roca, the former Argentine ambassador to the United States, and Robert Hill, the US ambassador to Argentina—sat in matching leather chairs to his left. Hill leaned toward Buckley; Buckley regarded his guest down the bridge of his nose. A photogenic coterie of young people—probably students at Lincoln School in Buenos Aires, where the episodes were filmed—sat on the floor, as Hill explained to Buckley and his diplomatic counterpart that Western reporting had downplayed the brutality of Argentina’s left wing and failed to account for the positive aspects of the country’s government, which was under international condemnation for brutal murders and disappearances of civilian dissidents.

“And that’s why your visit here is very important,” Hill told Buckley, the founding editor of conservative weekly The National Review, earnestly. “Because you’re respected in this country and you’re well known in international circles. And the opinions that you convey in the United States about your impressions of Argentina are a lot more important than Ambassador Roca and myself. So anything that you ask us today about Argentina we’re prepared to answer.”

“Okay. Okay,” Buckley said, fiddling with his pen. “Why is it that the Argentina story is so widely unknown in the United States in your opinion?”

“In my opinion, Mr. Buckley, I think one of the problems the Argentine government has is their lack of understanding of public relations,” Hill said. “We’ve talked about this several times with Argentine friends. They’ve recently retained a well-known firm in New York to represent them.”

It was the last of four episodes of Buckley’s Emmy-winning talk show Firing Line filmed in Buenos Aires. For Buckley, perhaps the single most significant intellectual influence on modern American conservatism, the trip held the prospect of a chance to weigh in authoritatively on what would come to be known as the Dirty War; it would also provide a chance for him to be seen with no less a literary light than Jorge Luis Borges—an interviewee for one of the four shows—who was, during the 1970’s, a vocal supporter of the Argentine military junta and its leader, president Jorge Videla.

According to documents obtained by CJR, the entire trip was a carefully stage-managed project of the junta itself, working with the American marketing and PR firm Burson-Marsteller, which kept a list of potentially sympathetic journalists for the use of the junta. On the list, next to Buckley’s name, someone from the firm had written, “could be convinced to make the trip to Argentina after the US elections.” And now, here he was.

By cross-referencing contracts and other documents from the PR campaign with episodes of Firing Line, diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks in 2010, and the NSA Archive Project, it is possible to gain a fuller picture of the role Buckley, and international media in general, played in helping to paper over the atrocities of the Argentine government.

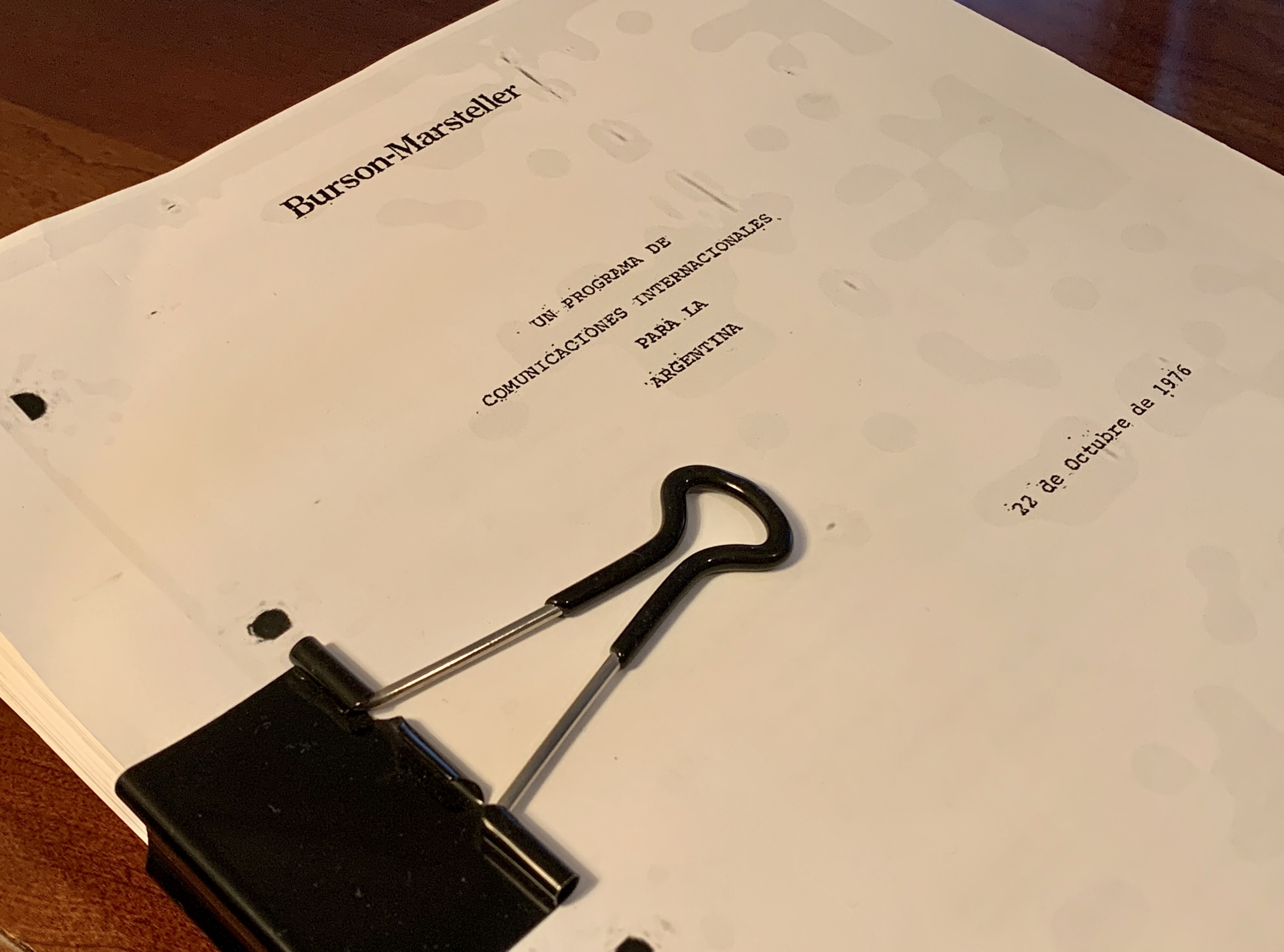

The full Burson-Marsteller program in Spanish. For the PDF and related documents, click here.

A more favorable image

The government had implemented a highly controlled communications structure that gagged the press inside Argentina. Beginning in June 1976, just three months after the junta took power, publicists at Burson-Marsteller signed a contract with the government to provide public relations services. In October of 1976, they delivered a 155 page document titled “An International Communications Program for Argentina,” describing how they planned to gain the help of international media in whitewashing the dictatorship’s crimes.

By August, those crimes were impossible for diplomats to ignore. “Vicious counter-terrorist reaction from security forces acting clandestinely including killing several priests and dumping of slaughtered bodies all over Buenos Aires, shocked many Argentines into new awareness of just how far things have gone,” wrote Max Chaplin in a cable to the State Department dated August 30, 1976. Right-wing death squads driving around in green Ford Falcons were operating in broad daylight. Buckley’s broadcasts were filmed just just a few months later. “Subsequent counter-terrorist kidnappings and murders, which now considerably overshadow efforts of leftist terrorists, have struck home among politicians and churchmen.”

Borges himself was mentioned in Burson-Marsteller’s communication program, under the “tourism” section, offered as a sort of cultural attraction for visitors. As one of the most famous Argentine writers and a fan of Videla, Borges was a perfect pawn for the public relations campaign. Burson-Marsteller had promised the junta it would emphasize left-wing terrorism “by providing vivid evidence of the brutality of the guerrillas or terrorists;” Hill, the U.S. ambassador, represented its interests faithfully in the Firing Line broadcasts:

Hill: What caused the human rights problem, Mr. Buckley, in your opinion, in Argentina?

Buckley: Well, what caused the human rights problem is a series of reports by people who are allegedly innocent who have disappeared, essentially, and the failure of the government to release the names of those who have disappeared.

Hill: No that’s not correct, in my opinion. The human rights problem was caused by the terrorists. They were killing innocent people. The first week I was in Argentina I left the residence one morning at quarter of nine and within three blocks a body was thrown in front of our automobile. Now the object of course was to have us run over the body and then blame the United States ambassador and the chauffeur for this incident. I sent toWashington in November ten pages of terrorist activity since I came to Argentina, ten pages. Some of them were frightening.

William F. Buckley and Jorge Luis Borges | Photo: The Hoover Institution via YouTube

Buckley comes to town

Uki Goñi worked from 1975 to 1983 for a small English-language newspaper called the Buenos Aires Herald, now famous for publishing names of disappeared people when virtually no other press inside Argentina would. Goñi remembered Burson-Marsteller’s work; journalists used to translate financial reports for them for extra money, he told CJR. Besides the publicity Buckley’s broadcasts and his columns helpful to the Junta, Goñi believes having a powerful PR firm from New York, and Buckley visiting, was a morale boost for the dictatorship and simultaneously demoralized journalists. At the time of Burson-Marsteller’s PR push, Robert Cox edited the Herald. Cox, who appeared on one of the four broadcasts, told CJR he had been warned by friends not to go on the show but thought he “might be able to get some of the true, grim reality across to a US audience.”

“The prevailing impression outside—and probably more so in Argentina—was that it had been a bloodless ‘velvet’ coup,” Cox said. Cox didn’t know Burson-Marsteller was involved in the press junket, but was aware of their work in Argentina. “I think it’s fair to say that Burson-Marsteller’s sophisticated propaganda helped to fabricate a web of lies that allowed the military to commit atrocities with complete impunity,” he said. “With a compliant press and total control of the air waves, the dictatorship was able to use Burson-Marsteller in creating a false image of Argentina at home and abroad.”

On January 31, 1977, Buckley interviewed José Alfredo Martinez de Hoz, the then-former Minister of the Economy during the dictatorship, who had signed several of the Burson-Marsteller contracts himself. Martínez de Hoz promoted the economic plans for Argentina, and stayed on message with the communications program, projecting an image of an improving, stable economy and a country that was ripe for foreign investment.

Martínez de Hoz was the first civlian former cabinet member to be arrested for crimes associated with the dictatorship. He was detained in 1988 but was later pardoned in 1990 under President Menem’s blanket amnesty laws. He was re-arrested in 2010, after those laws were declared unconstitutional, and accused of collaborating in the commission of crimes against humanity, specifically the 1976 kidnapping of father-and-son cotton export businessmen Federico and Miguel Gutheim, whose company, Sideco, was allegedly coerced into deals that favored the Videla regime, according to the New York Times. He died under house arrest in 2013 without being convicted.

Hill died in 1978. According to US diplomat Tex Harris, who died shortly after being interviewed for this story, the US embassy’s policy at the time was not to interview victims of human rights abuses—for fear of interfering in Argentine affairs.

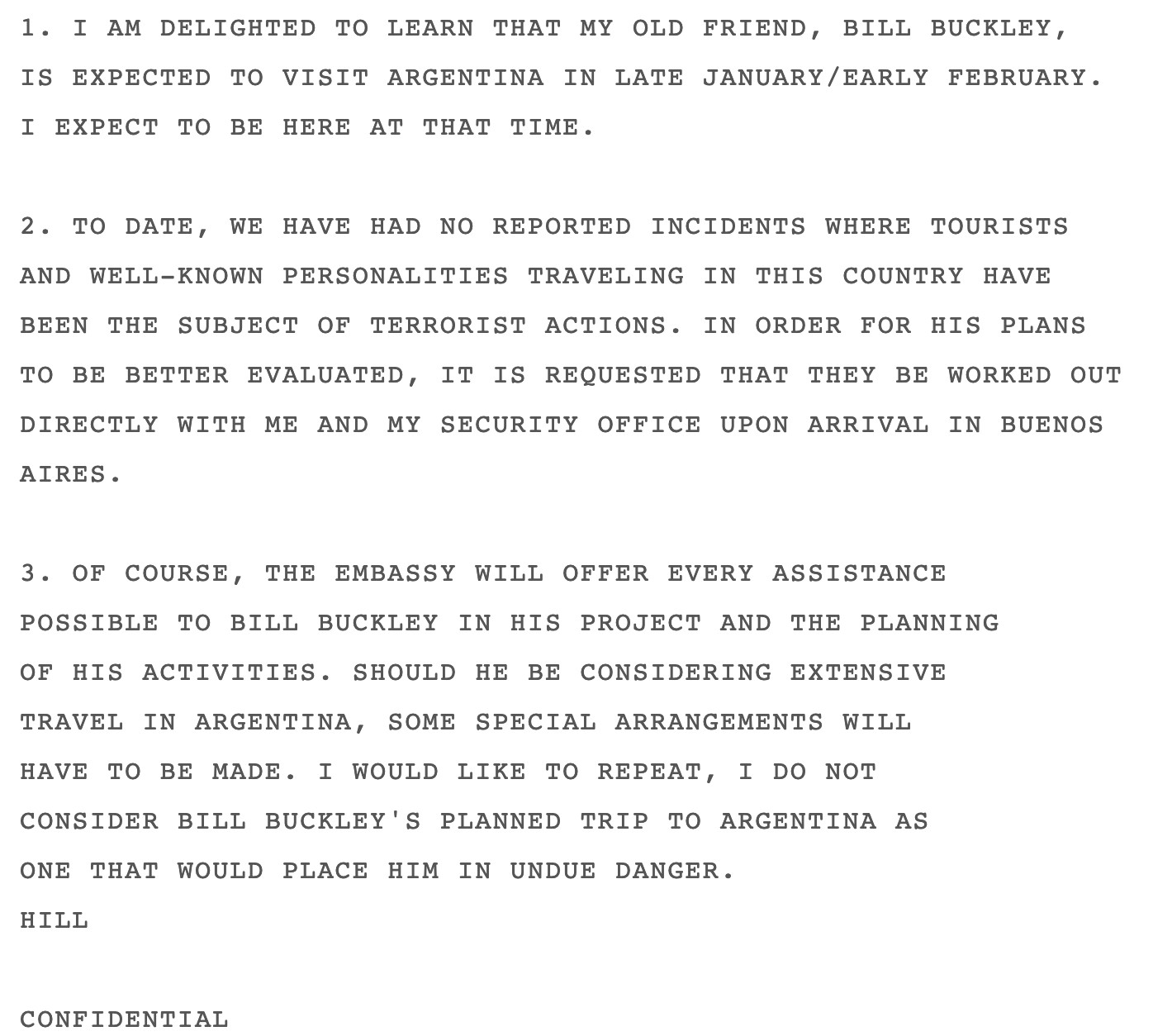

Diplomatic cable from Ambassador Robert Hill to Assistant Secretary Harry W. Shlaudeman, December 7, 1976 | Source: Wikileaks

Follow up and retraction

After filming in Buenos Aires, Buckley wrote a syndicated column describing left-wing militants in explicit detail and portraying General Videla as an “unusual creature” and “a reluctant president.”

He wrote two short sentences towards the end about right-wing violence: “It is extremely difficult to fine-tune an anti-terrorist campaign. People who reach for their pistols or their shotguns at the sight of a terrorist or a suspected terrorist are not trained at West Point.”

“The content of [the column] was about 100 percent consistent with [Burson-Marsteller’s] objective of defending the reputation of the Videla dictatorship.” writes Juan Méndez, a former detainee of the junta and former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, in his book Taking a Stand.

Years later in June 1985, Buckley published a retraction in the Washington Post. He didn’t mention Burson-Marsteller but he blamed the 77-year-old Borges and Cox for influencing his opinion.

Cox said that Buckley called him later on and asked, “Were we conned?”

Many more journalists and newspapers were mentioned by name in Burson-Marsteller’s program including Edwin Darby, then of the Chicago Sun-Times, syndicated columnist Ernest Cuneo, and Michael Frenchman of the Times of London. Buckley’s visit was just one component of a years-long campaign to influence public opinion and portray a brutal military dictatorship in a more positive light. But it is the most thoroughly preserved.

What long-term effects does this kind of propaganda have on our collective memory? How can the damage of high level disinformation spread by professional spin doctors be measured in retrospect? “I remember how I hated [Burston-Marsteller] for lies that cost lives and for which they were paid huge sums,” Cox told CJR. Nothing can bring 30,000 disappeared people back or provide closure for their families who will never know what happened to them, but can the damage done by the propaganda campaign waged against the victims be undone?

In 1985, Argentina used its own criminal code to convict the leaders of the dictatorship of war crimes in the historic Trial of the Juntas. Dozens of former military personnel and some civilians have since been sentenced for crimes against humanity they committed during the dictatorship. One hundred and thirty people who were stolen as babies by the Junta have had their identities restored thanks to human rights organizations which have worked tirelessly for almost forty years. But it’s likely impossible to fully correct the record after all this time.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.