Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

As Edward R. Murrow wrapped up his now-famous special report condemning Joseph McCarthy in 1954, he looked into the camera and said words that could apply today. “He didn’t create this situation of fear–he merely exploited it, and rather successfully,” Murrow said of McCarthy. Most of Murrow’s argument relied on McCarthy’s own words, but in the end Murrow shed his journalistic detachment to offer a prescription: “This is no time for men who oppose Senator McCarthy’s methods to keep silent–or for those who approve,” he said. “We cannot defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home.”

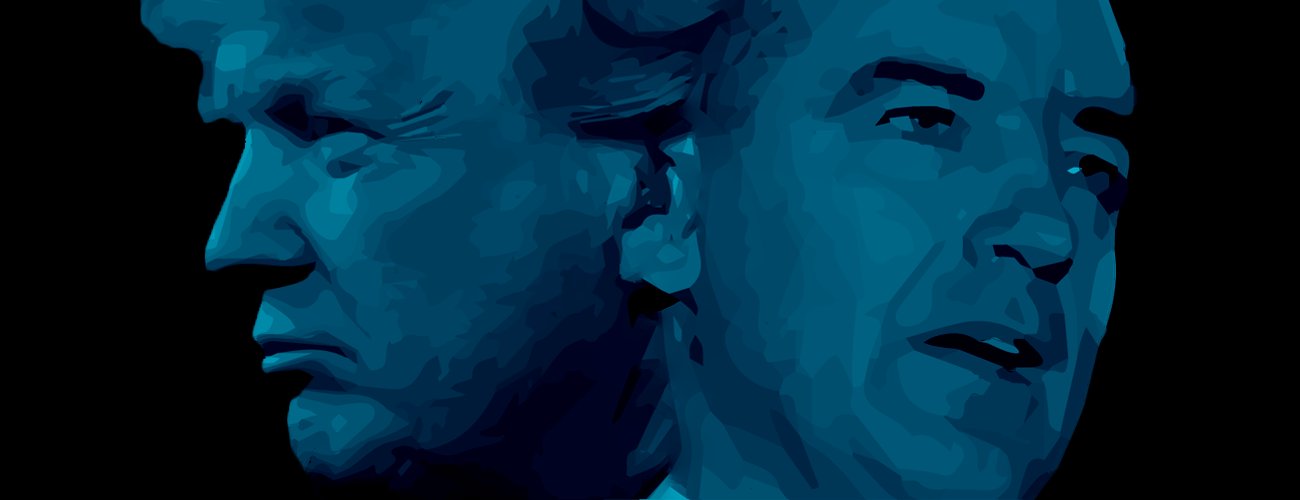

After months of holding back, modern-day journalists are acting a lot like Murrow, pushing explicitly against Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee. To be sure, these modern-day Murrow moments carry less impact: Long gone are the days in which a vast majority of eyeballs were tuned to the big-three television news programs. But we nonetheless are witnessing a change from existing practice of steadfast detachment, and the context in which journalists are reacting is not unlike that of Murrow: The candidate’s comments fall outside acceptable societal norms, and critical journalists are not alone in speaking up.

It’s difficult to find a single launch moment for the change in coverage, but perhaps it started with a question from Fox News’s Megyn Kelly during the August 2015 GOP presidential debate. Kelly simply listed some of the awful things Trump has said about women; the power of her question was her use of the candidate’s own words. As effective as Kelly’s question was–provoking Trump’s ire and countless tweets–journalists began to become more adversarial. The new tone began to ramp up in March when CNN’s Anderson Cooper took Trump to task. Trump, in defending himself after a squabble with fellow candidate Ted Cruz involving photos of each of their wives, explained to Cooper that Cruz had started it. “With all due respect, sir, that is the argument of a 5-year-old,” Cooper replied.

Others followed suit. In June, CNN fact-checked Trump in real-time with the caption “TRUMP: I NEVER SAID JAPAN SHOULD HAVE NUKES (HE DID).” And it was extraordinary to see CNN’s Jake Tapper asking Trump about his objections to US District Judge Gonzalo Curiel, who was born in the United States to Mexican parents. Trump contended Curiel’s background prevents him from making a fair judgment in a case involving Trump. “Is that not the definition of racism?” Tapper asked the candidate.

Last month, Trump sent a self-aggrandizing tweet about Orlando (“Appreciate the congrats for being right on radical Islamic terrorism.”) and intimated in an interview with Fox News that Obama may have had a role in the attack. (“We’re led by a man that either is not tough, not smart, or he’s got something else in mind.”) In response, Stephen Colbert took to his chalkboard on The Late Show to diagram Trump’s logic. The diagram was a swastika, a joke on a major network show that would have been inconceivable even a few months ago. After Orlando, the Los Angeles Times called Trump “a loose cannon” who was stooping to “a new low—even for him.”

The American journalistic goals of detachment and objectivity are long held. Until the mid-19th century, most newspapers were directly funded by political parties. As that started to change and the commercial model began to emerge, newspapers started to shed their partisan baggage. For much of the last 150 years the trade-off was a good one: Journalists would avoid taking sides, and they would be given access to newsmakers–and news consumers–from both parties.

Playing it straight can still be effective. Trump mocked a disabled New York Times reporter, revoked the credentials of The Washington Post, and insulted Megyn Kelly–responding, in each case, to straight reporting of facts. But facts alone may be a poor weapon against a campaign that rarely admits errors, choosing instead to double down on dubious claims.

So why the change in coverage? To understand this moment, and what it says about journalism’s place in our democracy, we need to explore two things that trigger journalists to call speech dangerous. The first is that journalists rarely shed their detachment in a vacuum. Murrow, the most respected television journalist of his day, wasn’t the first to criticize McCarthy. The Milwaukee Journal and other newspapers led the charge, and The Washington Post’s Herblock made McCarthy the subject of many of his cartoons. And while President Dwight D. Eisenhower resisted criticizing McCarthy forcefully, other politicians began to, particularly when McCarthy’s targets included Protestants and the military, as the Army-McCarthy hearing would reveal.

Throughout American history, journalists have been more likely to become advocates when they see others, like politicians and protesters, speaking loudly in dissent. When Walter Cronkite went on television in 1968 after the Tet Offensive to conclude that “we are mired in stalemate,” he did so after much of America had come to the same conclusion.

That the vast majority of Democrats and quite a few Republicans (some of whom will boycott their convention) speak out publicly against Trump gives cover to journalists who choose to depart from the usual practice of studied balance. When you have the Bush family boycotting the GOP convention and George Will, the leading conservative journalist of the past four decades, leaving the party over Trump, it is easy to see that the political world has been overturned.

The second condition for mainstream journalists to abandon their detachment is when a politician’s words go way beyond the pale. More than his vocal critics, the words and ideas of Trump himself are causing journalists to change their role. To understand this, it is useful to look briefly at a theoretical construction of objectivity by a leading journalism historian, Daniel Hallin, who sees the world of political discourse as falling into three concentric spheres: consensus, legitimate controversy, and deviance.

The sphere of consensus is the inner circle, the place in which most people tend to agree. Most American journalists and news consumers would agree on the legitimacy of the government as embodied in the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and Amendments.

The sphere of legitimate controversy includes the questions within the standard political debates: How much should the rich pay in taxes? Should the US expand offshore drilling? Is universal health care a desired outcome?

Then we have deviance, the place in the diagram which falls outside the bounds of journalistic conversation. This includes issues such as: Should the US be violently overthrown? Should we ignore the Constitution? Often, as in the above example, the first and last spheres operate as opposites: Everyone agreeing with the sphere of consensus would uphold the Constitution; the deviants might overturn it. These spheres also shift from time to time, as politicians and journalists and the public shift their views. The support of two issues–the full citizenship of African Americans and a woman’s right to vote–moved over time from deviance to legitimate controversy to its present position: deeply embedded in the sphere of consensus. In the span of about 20 years, same-sex marriage evolved from legitimate controversy and is well on its way to consensus.

Where does Trump’s speech fall? Some predicted that his opening announcement, with its salvo about Mexicans, represented a descent into deviance that would be unpalatable to the voters. Some observers assumed that labeling Senator John McCain and other POWs “losers” would finish him. “I like people who weren’t captured,” he said in July 2015. But the stakes weren’t high yet, and Trump brought in skyscraper-sized ratings. “It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” said Les Moonves, that network’s CEO.

The declining audience for traditional news is well documented and creates twin pressures. First, the desperation for audience share–an estimated 80 million viewers tuned into the networks’ coverage of McCarthy’s hearings about the Army following Murrow’s show. These are ratings numbers that the networks cannot replicate now. Second, networks cannot replicate the influence that Murrow, Cronkite, and others had–on Election Day (November 8), we will be eager for signs to see if today’s journalists pushing back against Trump actually stop him. Specifically, we’ll want to look at whether journalists are still able to set the tone, despite the diminished audience. And what role do Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other platforms play in multiplying the national conversations that once raged around actual water coolers?

We’ve reached a turning point, and the two criteria for journalists to abandon their objectivity have come to pass: Trump is widely criticized, even by his own party, giving journalists a lot of company in their criticism of him. When Trump suggested that Judge Curiel was incapable of trying a case because of his parents’ birthplace, even House Speaker Paul Ryan, a fellow Republican, called the comments “racist.”

And Trump’s views appear increasingly deviant. No respected journalist would seek a balancing quote from someone who held such a view about a judge or who suggested, as Trump did last month after the Orlando shootings, that a sitting president was in cahoots with a mass murderer.

Murrow felt compelled to end his broadcast by warning his audience about the dangers of staying neutral, as journalists too often do, when the stakes are high: “Cassius was right,” said Murrow. “‘The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.’” If a politician’s rhetoric is dangerous, Murrow implied, all of us, including journalists, are complicit if we don’t stand up and oppose it.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.