Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Journalists love debating what constitutes ethical journalism. Should we show pictures of the shooter in a mass-casualty incident? Is it ever okay to pay a source? Should we use photographs taken without permission? What about publishing classified documents? When is it okay to identify the author behind an anonymous social account?

The debates are necessary. Journalism has the power to cause disruption and harm to those we cover, whether individuals, businesses, or governments. It’s only right we hold ourselves to account.

But they can also be insufferable. Debates about rules tend to attract those for whom the narcissism of small differences is a way of life. This is, not least, because these debates are fundamentally unresolvable.

We don’t have one fixed, underlying philosophy of journalism to which every newsroom subscribes. In reality, we probably don’t have a single newsroom in which every editorial staffer feels the same way.

Here, drawing from a few thousand years of political thought, are five potential newsroom philosophies, into which you can categorize different outlets at your leisure.

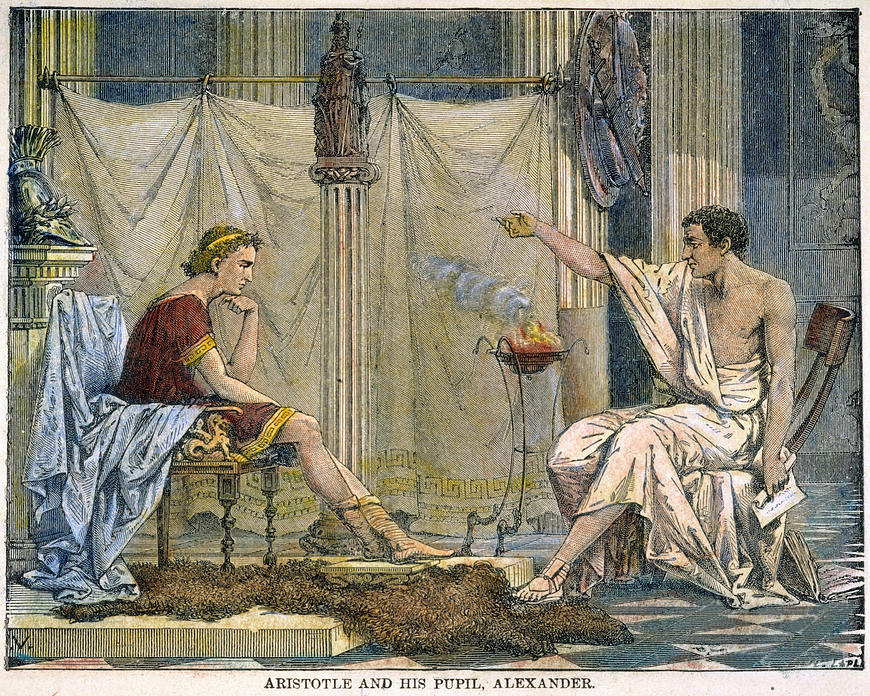

The Aristotelian Newsroom

On the surface of it, doing what Aristotle thinks we should do seems simple: we should act virtuously for its own sake—and want to do so, rather than regarding it as resisting temptation. The difficulty comes with agreeing what counts as “virtuous.” For Aristotle, society should come together and mutually agree on what counts as virtuous, and then citizens should try to model those values.

That’s difficult enough when your society is small. In a modern, diverse society it can seem impossible. Is truth a virtue or is profit? What happens when they’re in conflict? Telling the truth because it was good for profits, if profit were not intrinsically virtuous, would not qualify as ethical for Aristotle—so if any newsroom wants to claim Aristotelian values, you can bet it’s going to be a not-for-profit.

The Deontological Newsroom

Deontologists—among whom Immanuel Kant is most famous—are most concerned with our duty or obligations to one another, or to society. For them, the consequences of an action don’t matter—what matters is whether it follows the rules we have agreed on as a society.

This can set a very high bar for actions: it might make sense that driving when drunk carries the same penalty whether or not you run someone over, but most of us blanch at a moral code that says if a murderer asks you where to find his would-be victim you should tell the truth.

A deontological newsroom would be difficult to run. It would hold that if it is ever wrong to breach someone’s privacy, it’s always wrong. If it’s ever wrong to keep a secret (such as a source), then it’s always wrong. An in-house corporate media operation staffed solely by true believers might manage to operate in this way, but any other newsroom would quickly run into trouble.

The Utilitarian Newsroom

This newsroom all but flips the philosophy of the previous one on its head: for utilitarians, consequences are pretty much all that matters. In a given situation, we should choose the option that delivers the greatest public good.

In practice, almost every working public-interest newsroom operates under this philosophy—knowingly or not, and even willingly or not. We have built into both law and industry requirements for public-interest tests—journalists are allowed to breach people’s privacy provided the overall public good is served by doing so.

The court case usually ends up being decided on whether or not the newsroom got the balance right.

The Machiavellian Newsroom

The previous philosophy might sound a little too high-minded as an explanatory tool for the actions of some newsrooms—and particularly for some proprietors. For those newsrooms, readers may be tempted to consider the political philosophy of Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince, drafted while in prison in a bid to secure his release from the titular ruler.

Machiavelli is credited as the inventor of realpolitik, of being willing to be devious (or at least practical) to secure advantage in existing political structures. If you’re the owner of a newsroom, then you have a very particular kind of asset—the attention and the trust of your audience—which can, if used judiciously, be leveraged for other kinds of advantage.

This could—purely hypothetically—be used to pursue the political agenda of an owner, or else to confer status and access to those in power, or even to secure suitable regulatory decisions or appropriate modifications to competition law. The possibilities might be endless.

The Nihilistic Newsroom

Nihilism more or less states that nothing matters, so you may as well do what you want. To the jaded, most newsrooms are already here, except worse. One editor described the prevailing ethos of journalism in 2022 as: “psychopathy (anything for a click) and zealotry (my tribe is right).”

Hate-clicks count just the same as worthier ones, after all. Everyone else is making up stories, so why not join in? Why not indulge in a little light plagiarism, as a treat? And why not ruin someone’s life, if that person happens to belong to a different political tribe and you’re in a bad mood?

There is certainly something tempting about it, at least now and then. But isn’t that what social media is for?

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.