Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

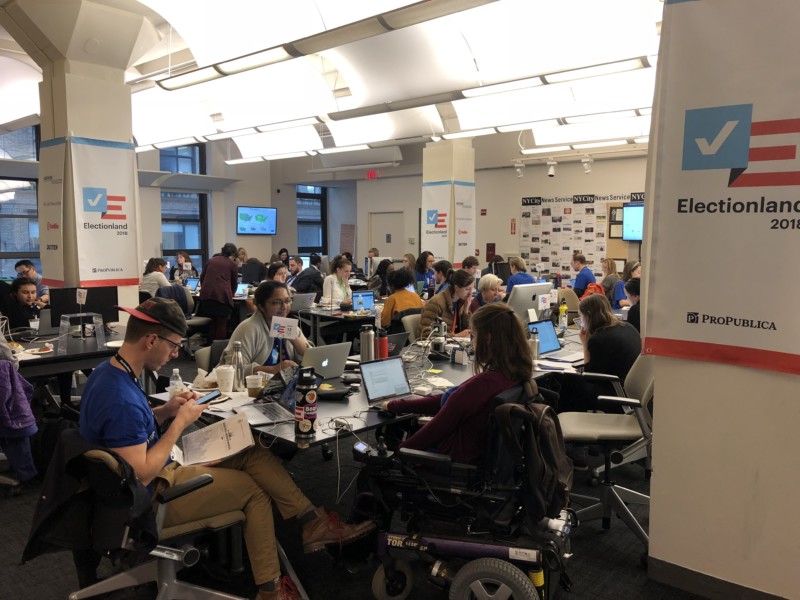

At 6am on Election Day, journalists began arriving at The City University of New York’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, in midtown Manhattan. There as part of Electionland, a project started in 2016 by ProPublica to collect information about voter disenfranchisement and feed tips to local reporters, some 80 journalists (from ProPublica and elsewhere), students, and experts in cybersecurity, misinformation, and law huddled around laptops at tables arranged cafeteria style. Their command center would serve 250 reporters in 125 newsrooms, many of which have seen their budgets diminished in recent years. ProPublica employees wore bright blue T-shirts decorated with stickers that read “I covered voting.” On large monitors near the front of the room were three maps of the United States; on one of them, clusters of tiny pink dots blinked and pulsated. They were news tips.

“As an investigative newsroom, we don’t really play a role on Election Day,” Scott Klein, ProPublica’s deputy managing editor, said. Klein, who wore black glasses and an Apple watch, sat at his laptop scrolling through a Slack channel where “catchers” dropped tips that had been cleared by editors. He conceived of Electionland alongside Simon Rogers, a data editor at Google, after seeing a report that in 2012 between 300,000 and 500,000 would-be voters had been disenfranchised due to long wait times. “How can we help?” they’d thought. “Instead of second or third day stories about all the people who abandoned the line, we want to speed it up so election officials can fix it and those people can vote,” Klein explained. “If we can get them their franchise, that’s impact for us.”

Beena Raghavendran, a young woman in glasses and slip-on sneakers, is an engagement reporting fellow at ProPublica and was tasked with fielding tips submitted by voters in Maryland, Maine, and Connecticut. Throughout the day, ProPublica collected reports through a call line manned by lawyers, a WhatsApp number that people could text, a web form at the news outlet’s site, email, and social media—all sent into an internal system called Landslide. Raghavendran flagged a tip, submitted through text message, which said that voters at a polling site in Baltimore had not been able to cast their ballots because scanners were broken. By the time Raghavendran got in touch with the source to vet the information, the problem had been resolved. But a new one cropped up.

The same tipster reported that poll station volunteers at the Enott Pratt Free Library, in midtown Baltimore, had neglected to provide voters with a second page on the ballot. Nobody noticed until a man waiting in line asked how to vote on city provisions. “The gentleman had remembered there was a second page to the ballot,” the tipster told Raghavendran. She jotted down some notes. A colleague scanned Twitter looking for other voters experiencing the same problem.

After talking with the source, whose name was Alexandra Adams, Raghavendran passed the tip on to Deb Belt, an editor on Patch’s national desk. Belt emailed the information to a reporter named Elizabeth Janney, who covers Baltimore. “There was a phone number, so I contacted the tipster and asked them to walk me through what happened when she got to the poll site,” Janney said.

Adams, Janney learned, had arrived at the library at around 6:50 in the morning. The ballot scanners were down and the first votes were not cast until nearly forty minutes after the poll site officially opened. When the man in line ahead of Adams realized that their ballots were missing a page, poll workers dismissed him, insisting that he’d been given a complete form. The man persisted, however, showing them a sample ballot on his cell phone. “It was a little frightening,” Adams told Janney. Eventually, the poll workers retrieved a box full of the complete ballots—but not before between 40 and 50 voters had already filtered in and out of the library.

Janney got off the phone with Adams and called the local Board of Elections, which did not give her an interview. Her story was published before lunchtime. In an interview with The Baltimore Sun, Armstead Jones, the city’s election director, denied that voters had been given incomplete ballots, but then sent two officials to the library to offer assistance. Janney’s story mounted pressure for a fix, and without the help from Raghavendran, she said, “I wouldn’t have been able to get in contact with Adams so quickly.” Later in the day, she was back to collecting more tips, via the Electionland Slack channel, on potential missing pages from ballots around Baltimore.

Back at Electionland headquarters, more tips were filtering out to cities elsewhere in the country. ProPublica catcher Maya Miller interviewed Rolanda Anthony, who reported on Facebook and in a call that a poll worker had yelled racist remarks and pushed her as she attempted to vote. Miller sent a transcript of the conversation to Matt Dempsey, a data editor at The Houston Chronicle, who quickly wrote and published a short article before dispatching Gabrielle Banks, a reporter working in the field, to Anthony’s polling site to fully report the story. (The poll worker was later charged with assault, and a second worker resigned in protest.) In Missouri, a poll worker, when presented with an American passport as identification, inexplicably asked the voter if he was “a member of the caravan,” referring to a group of Central American refugees traveling north through Mexico. A computer glitch in Geauga County, Ohio, incorrectly marked voters as having submitted an absentee ballot. The ProPublica team also tracked the performances of county and state election websites, many of which—in such places as Kentucky, Washington, and Texas—crashed periodically throughout the day.

Electionland staffers continued working late into the night as extra hands for comprehensive, data-based coverage. “I’m one person, and we have a team covering the state,” Janney said. “But we don’t have our own tip line or people on the ground everywhere. At the end of the day, it’s about providing a service to voters.”

ICYMI: WNYC’s nightly bid to put America in conversation

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.