Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

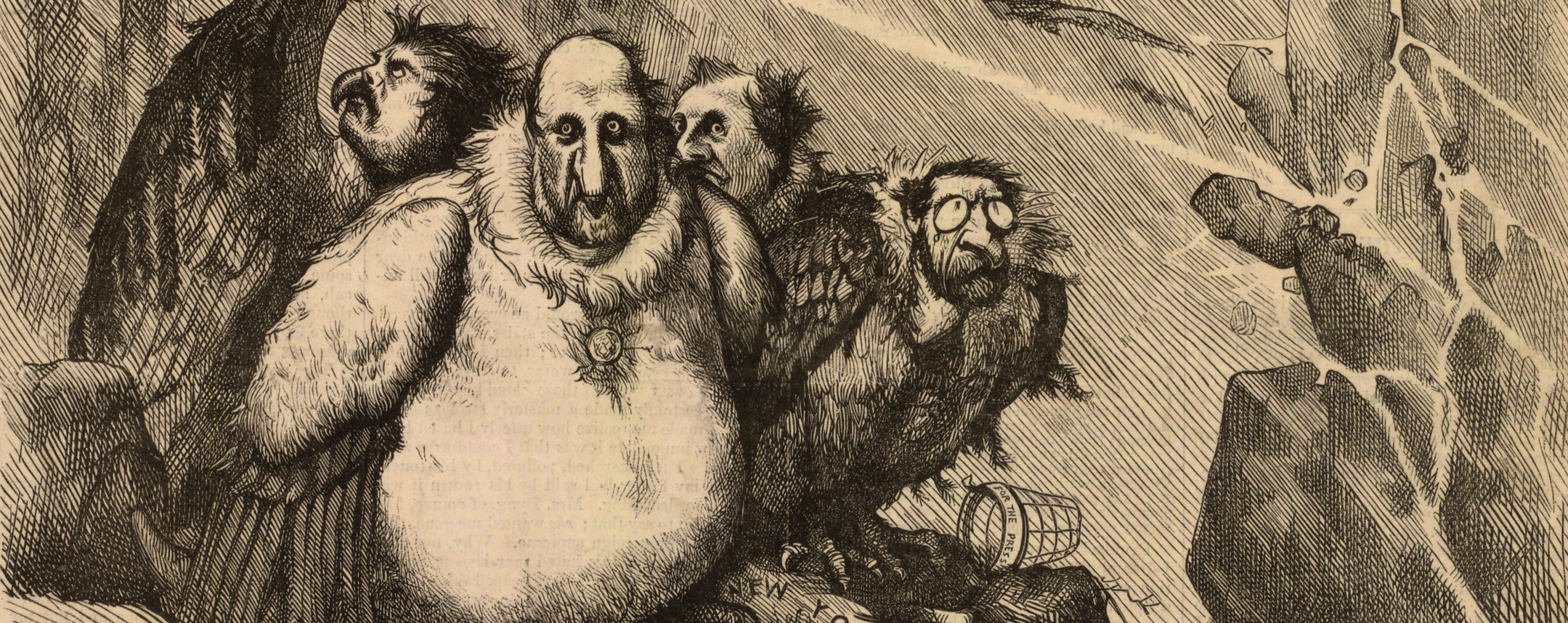

The fury cartoonists inspire is as old as the form. In 1871, William “Boss” Tweed, the political master of New York’s Tammany Hall, is said to have groused about caricatures of him drawn by Thomas Nast, often called the father of the American cartoon. “Can’t you stop those pictures?” Tweed complained. “I don’t care what they write about me, but these infernal pictures hurt.” In many ways, the unmatched ability of cartoons to quickly and efficiently insult is ideally suited to our era of Donald Trump and outrage clicks—for better and for worse.

“It’s immediate,” Eli Valley, a cartoonist, says of the rage inspired by his comics about United States-Israel politics. “There’s a much more visceral reaction to graphic imagery,” he adds. Matt Wuerker, the cartoon editor at Politico, says, “We’re perfect for the short attention spans of the clickthrough age we’re living in.”

But trouble arises when the targets of cartoons conflict with the interests of management. Last year, after Rob Rogers, a cartoonist for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, enraged his publisher with a cartoon about Donald Trump’s trade policies, he lost his contract there. In a piece for the Times, Rogers, who had been cartooning at the Post-Gazette for 34 years, wrote that John Robinson Block, the paper’s owner, had demanded that Roger’s “views should reflect the philosophy of the newspaper,” which had endorsed Trump for president. Later, the Post-Gazette replaced Rogers with a conservative artist.

ICYMI: In Pittsburgh, an unprecedented blow to editorial cartoonist

In April, after the Times international edition published an antisemitic cartoon, James Bennet, the opinion editor, who oversaw cartoons, disciplined the production editor responsible and dumped the syndication service that had provided the offensive image. Two months later, Bennet vowed to never publish a cartoon in the international edition again. Patrick Chappatte and Heng Kim Song, the international edition’s two in-house cartoonists, who had nothing to do with the image in question, lost their jobs. Joel Pett, a Pulitzer-winning cartoonist, called the move “chickenshit.”

In June, Michael de Adder—a cartoonist on contract for 17 years with Brunswick News, which syndicated his drawings in four Canadian newspapers—posted a cartoon to Twitter: a putter-toting Trump stands next to a golf cart on the shores of the Rio Grande, over the corpses of drowned migrants, asking, “Do you mind if I play through?” The cartoon got about 11,000 retweets and more than 20,000 likes; it also received nearly 4,000 replies, many criticizing him for denigrating the president. Within a day, the Brunswick News said it was ending de Adder’s contract.

Cartoon for June 26, 2019 on #trump #BorderCrisis #BORDER #TrumpCamps #TrumpConcentrationCamps pic.twitter.com/Gui8DHsebl

— Michael de Adder (@deAdder) June 26, 2019

It wasn’t just a single cartoon that cost de Adder his job, he says: “It was probably a series of Trump cartoons. That one probably quickened the pace out the door.” A freelancer, de Adder relied on the Brunswick News for 40 percent of his income. Immediate aid came from The Nib, a comics publication, which bought the viral cartoon from de Adder in a show of solidarity.

Within a week, however, The Nib’s publisher pulled its funding—which doesn’t bode well for other cartoonists seeking refuge from timid papers. And without more grand experiments in comics journalism, opportunities for cartoonists who want to publish political commentary will slip away. Mad, a haven for cartoonists for 67 years, shipped its final issue in August. Where there were more than 2,000 staff cartoonists at work a century ago, and 180 as recently as the 1980s, contemporary estimates are grim: a 2011 survey by The Herb Block Foundation, an educational nonprofit, estimated that fewer than 40 such jobs still exist.

Many cartoonists have turned to crowdfunding and direct-to-consumer publishing efforts such as Kickstarter and Patreon—unlike in traditional media, on the internet, it pays to provoke—but even stars can’t expect to make more than a couple thousand dollars a month. Older cartoonists sell books. Berkeley Breathed, creator of a political humor strip called Bloom County, recently resurrected it, for free, on his Facebook page.

“I’m feeling that pinch,” says Peter Kuper, whose political cartoons have appeared in The Nib, Mad, The New Yorker, and elsewhere. “I also have a career’s worth of experience that means I’m always trying to jump to a new rock. The problem is that the rocks are now underwater.” Still, Kuper has regular customers, notably The Nation, and even if he loses every paying gig, he says he’ll stay around. “Thank goodness for the internet,” he adds. He draws a new cartoon every day, even if only to post it on Twitter. “I do it for my own sanity.”

Wuerker, of Politico, is hopeful that the enduring power of cartoons will create more openings for publications aiming for impact online. There’s one promising opportunity: in August, Wired began publishing cartoons daily. “The future can be laughed at,” declared editor Nicholas Thompson. The ability of cartoons to provoke, Wuerker says, is “something that news outlets should harness.”

Related: Artist behind infamous New Yorker cartoon on the craft, his inspiration

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.