Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

A viral pandemic isn’t the same thing as a war. But as I’ve tried to work and lead a semblance of normal life in New York under covid-19, I’ve found myself drawing on my experience as an involuntary shut-in during some of the worst violence in Iraq.

I covered the US invasion of Iraq for the Boston Globe, and in April 2003 set up a long-term base in Baghdad in a hotel called the Hamra. At that time, journalists roamed the country freely, interviewing everybody—militiamen resisting the American occupation, Al Qaeda sympathizers, victims of Saddam’s brutality, survivors of indiscriminate American fire. We talked to clerics, politicians, stay-at-home mothers, political activists. The occasional flares of violence were localized and targeted.

To work outside of Baghdad we would wake before dawn and drive sometimes five or six hours to reach remote villages or cities. If the story called for more time on the ground, we would sleep at simple hotels, or on the floor of a contact we had befriended in the course of reporting.

Human beings are incredibly adaptable. We can get used to virtually anything. Wartime Iraq entailed a predictable level of instability and violence, and most activities seemed safe enough. The greatest danger was bad luck—finding oneself near an American convoy that might get attacked or, for us foreign journalists, getting kidnapped by an opportunist looking for ransom money.

In New York under corona, the shift from normal life to lockdown occurred gradually then all at once, over the course of a few short weeks. In post-invasion Iraq, that transition took more than a year. The threats multiplied until they became ubiquitous. There were numerous uprisings against the US occupation. Extremist groups like Al Qaeda kidnapped and murdered civilians, Iraqis as well as foreigners. Like everyone in Iraq, we feared death, dismemberment, and beheading—threats so commonplace that militants circulated recordings of their most grisly crimes on DVD.

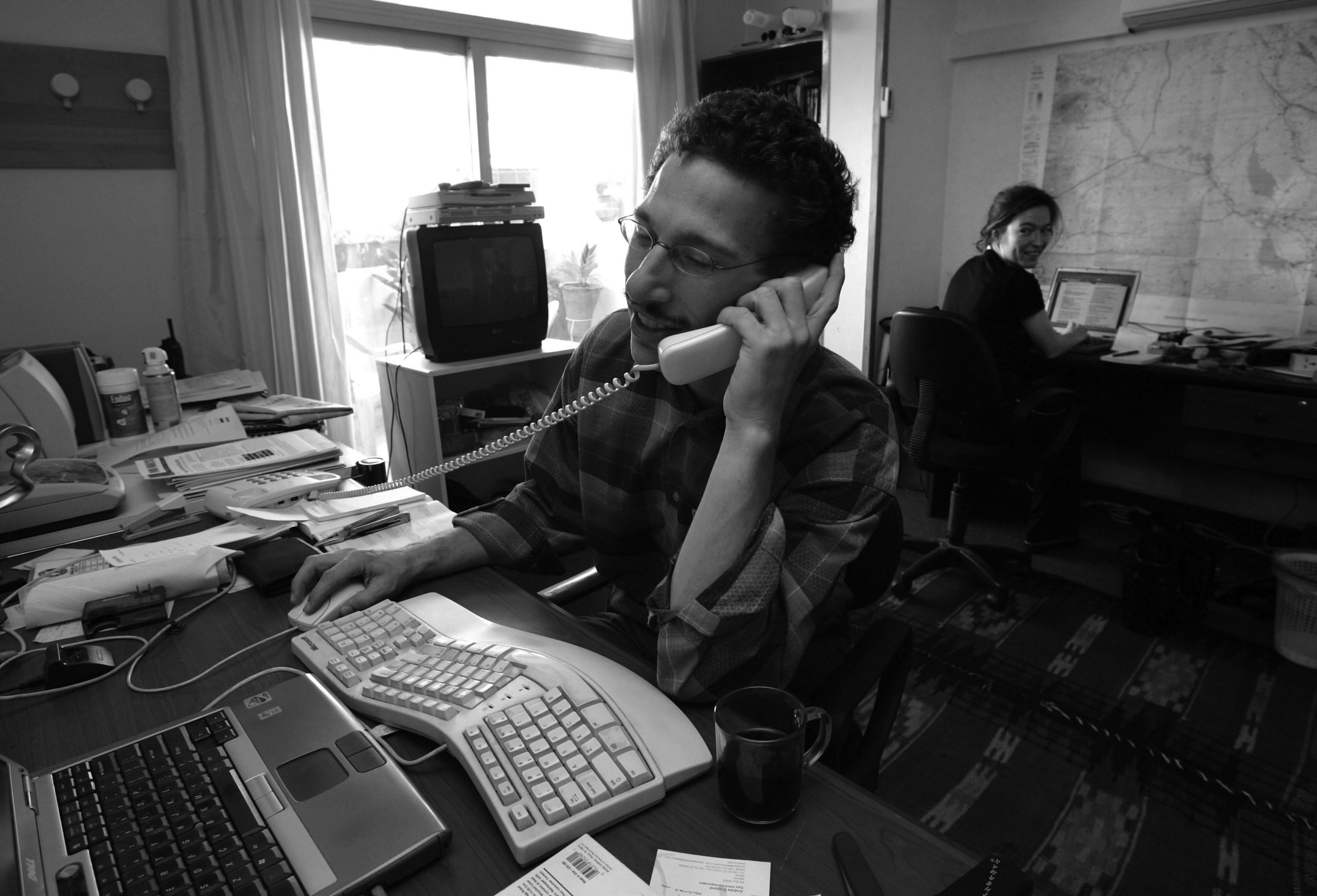

By the fall of 2004, any trip outside the Hamra was dangerous. At the same time, there was no option to simply hunker down at home. This was a long-ago era, before smartphones and ubiquitous chat and video communications. Even cellphone communication was unreliable. To reach the outside world, we relied on an expensive and very slow satellite internet connection, which was regularly disrupted by bad weather.

So how did we do our jobs? The same way that everybody gingerly got on with the necessities of life: calculated risks and extreme logistics.

In practice that meant learning how to manage the ambient fear and anxiety of possible death. In order to minimize the threat for everyone on our team, we planned obsessively and rationed the risk. We ruthlessly prioritized our reporting agenda. Simple news dailies were less important than investigations and features. For every interview, we considered whether we could talk to the subject by phone, or whether the subject could safely meet at the Hamra. If we concluded that an in-person interview was indispensable, we considered possible safe meeting places. If we trusted the source, we would consult them. If the source was also a possible threat—sometimes the case with militants or extremist sympathizers—we would share our meeting plan at the last possible moment.

Every reporter and researcher knows that nothing beats getting out of the newsroom—or, in our case, the tiny home office on the Tigris. Phone calls or online chats never substitute for meeting someone in real life. We lost a great deal of information by sacrificing all but the most critical encounters. Our remaining outings took on an outsize significance, planned like a backwoods hiking trip or a military operation. We would share our planned route and return time with a colleague who was staying in. We carried long-range walkie-talkies as backups to our unreliable cellphones. We had a chase car follow behind us, to deter any possible kidnapper or at least to be able to report any harm.

As time passed, the risk of staying home grew as well. There were violent groups that targeted foreigners and foreign journalists. A suicide bomber could target the hotel. And eventually one did, in November 2005, destroying the smaller of the Hamra’s two residential towers (the first of several attacks on the hotel, culminating in its closure in 2010). I happened to be out of the country on break at the time, along with the co–bureau chief (and future wife). When we returned, we carried on our existing regimen of limited hibernation and quick forays into the city.

ICYMI: When an election year becomes a sideshow

The planning—as well as the makeshift (and mostly symbolic) security—enabled a mindset that comes in handy in quarantine. In wartime, there’s simply no such thing as zero-risk. In order to eat, work, or see the sun, you have to expose yourself to dangers that go beyond the quotidian dangers of daily life.

We trained ourselves to assess risk dispassionately. Every day we would ask what had changed: which areas were now unsafe, what techniques were being deployed by which violent groups, who was being targeted. The situation changed day by day. So did our capabilities; someone might offer a ride in an armored car to an otherwise hard-to-reach area. Those of us who disliked the limitations of embeds with the US military would accept a military flight to a part of the country not safely visited by road.

When we acquired a chase car and an armed guard in 2004, a year into the American occupation of Iraq, we were able to travel more freely. And when militia groups declared cease-fires, we could travel to areas that days earlier had been pitched battlegrounds. Nothing was entirely safe, and a few things were obviously too dangerous. But on the spectrum in between those two extremes, we were able to do quite a lot of reporting. We dressed to blend in, so that a casual would-be kidnapper wouldn’t quickly notice us as foreigners. I grew an embarrassing tiny mustache, which is all I could muster.

Sometimes we reported what we could, rather than what we thought was most important. Despite the drawbacks of embedding, we sought trips with the military just to get out into the country. Entire areas and demographics were off-limits. I could easily visit the Shia clerical centers of Najaf and Karbala, but Basra and Mosul were more difficult and Anbar Province almost completely out of bounds. Iraqi reporters were able to travel a little more widely, but the epicenters of the conflict—including some of the most newsworthy places, like Fallujah—were off-limits to them as well. Some factions, like the religious Shia militants, were eager to meet journalists and explain their motives. Others, like the burgeoning ranks of Al Qaeda fighters, considered journalists fair targets. As a result, we were unable to report effectively on the communities where Al Qaeda and similar extremists made their bases.

Given the drawbacks and risks, we considered it crucially important to keep ourselves sane. We sought to cultivate psychological well-being of a sort—a “good enough” principle for mental health. Even as violence intruded more and more into Baghdad life, the community of reporters at the Hamra continued normal life in an effort to stay balanced. We went out to dinner at restaurants, organized outdoor barbecues, accepted invitations to people’s homes for meals, and visited cultural sites. By the fall of 2004, with the threats proliferating, all that sort of recreation ceased. No more water polo games and midnight swim races at the Hamra pool; no more outdoor parties on the hotel terrace.

READ: The Tow Center COVID-19 Newsletter

But we maintained a strict regimen of self-care, and assiduously carved out time and space in our home for not working. We decreed one area of our suite off-limits for professional activity; it was a strictly recreational zone. Exercise was critical; we ordered a rickety elliptical machine and worked up a sweat on it every day—especially on those days when we were unable to leave the compound at all or when the news kept us hunched over our laptops for twelve to sixteen hours. Every night, no matter how pressing the deadline or how ghastly the news, we blocked out an hour to prepare dinner ourselves and to eat together. If possible, we invited another reporter from the Hamra complex to join us. Every night before bed, we read or watched a DVD (remember, this was before the days of streaming). And finally, we made a point to check in with each other and talk about our fears and worries, even if only for ten minutes.

It’s arguable how well these approaches worked for us, and whether they carry over from wartime to pandemic. I spent a total of three years full-time covering Iraq, from 2003 to 2006. During that period my co–bureau chief and I got married and decided that we needed a safer, more predictable daily life. Constant danger and decision-making put us in a state of unending hypervigilance, from which it took years to come down. The demands that the covid-19 pandemic places on essential workers cause a similar, enervating mix of adrenaline and exhaustion.

We weren’t caring for children while working at the Hamra, the way we and so many others are now while working from home. Older technology kept us disconnected from friends and family (no FaceTime with stateside parents and siblings from a Baghdad traffic jam), but that disconnection was also a blessing—it saved us from the psychological dislocation of trying to connect simultaneously with people who shared the stresses of our environment and with people far away who lived under completely different conditions.

Covering a war while living in that war can make a person a little bit crazy. Some psychic toll is an unavoidable cost of trying to function at a time of historic stress. Knowing that means I’ll be less surprised by the ups and downs of working through an extended lockdown. Even apocalyptic times eventually come to an end.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.