Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Journalists favor the serious and the certain. In an unserious, uncertain world, we must learn to embrace some difficult new topics. One particularly pressing issue: stupidity.

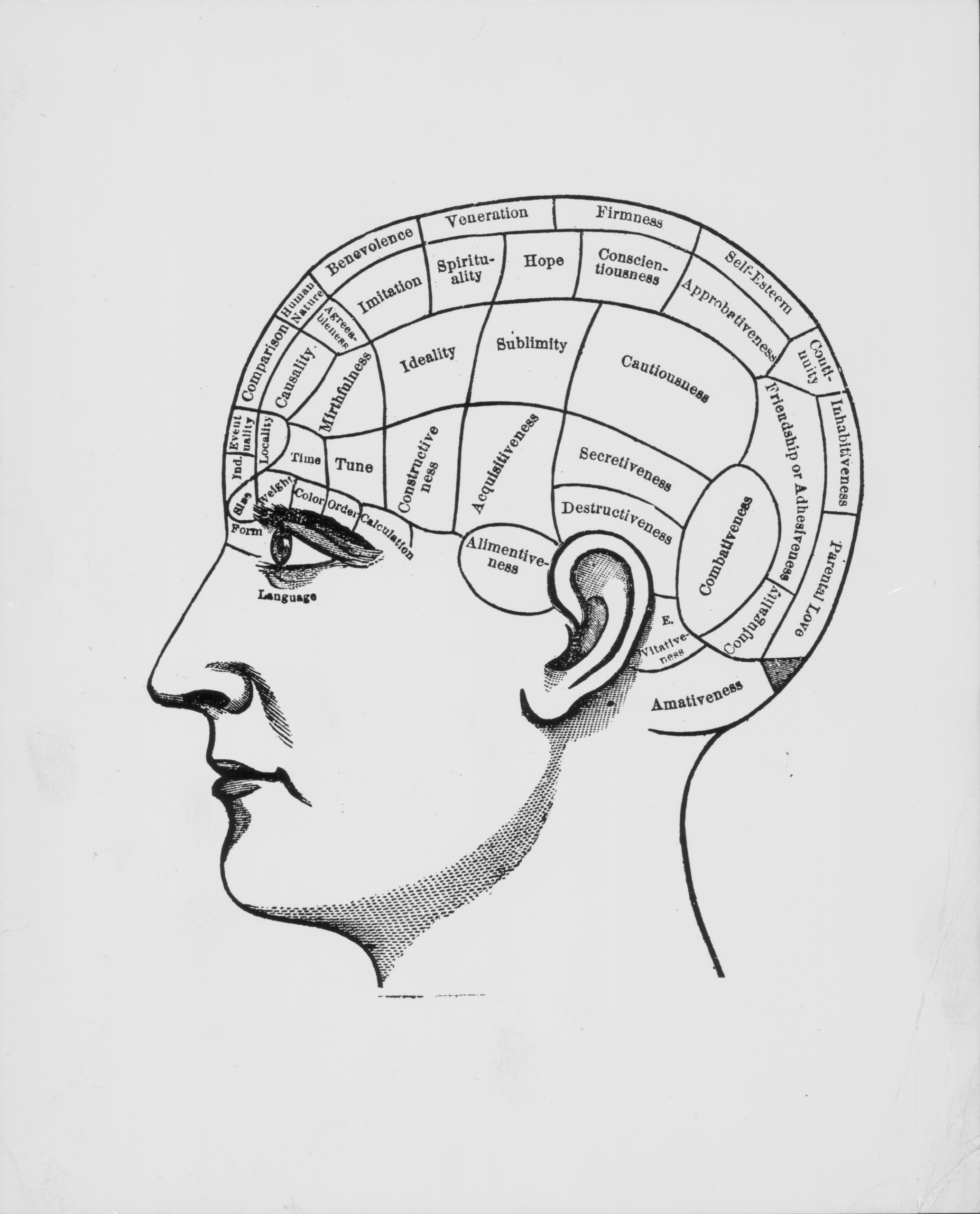

A number of European writers have tackled this subject in recent months. In Homo Cretinus, Olivier Postel-Vinay describes stupidity as a “mental polyp” that subtly encloses specific brain regions, impairing cognitive flexibility. This form of stupidity, he said in an interview, is not an occasional lapse or lack of knowledge but an “attack on intellectual integrity” that renders us incapable of exercising common sense.

“Our societies have never known such a high level of education, which obviously doesn’t prevent the development of stupidity,” he says. For Postel-Vinay, stupidity transcends ignorance because it operates even in highly informed individuals, who remain ensnared by rigid beliefs.

Such beliefs lead people to ignore contradictory information and select the evidence that supports their ideas. Postel-Vinay defines this confirmation bias as the polyp’s “tool of choice” because it perpetuates a self-reinforcing cycle of false beliefs that impedes intellectual development. Thus, he says, opinions become dogma in even the most intelligent individuals. Social media echo chambers only make the situation worse.

In his recent book Elogio dell’ignoranza e dell’errore (In Praise of Ignorance and Error), the Italian writer and former prosecutor Gianrico Carofiglio distinguishes between two types of ignorance: unconscious ignorance and conscious ignorance. The former, he said in an interview, is particularly dangerous to democracy because it combines a lack of knowledge with the arrogant belief that one already knows enough.

“Unconscious ignorance undermines the foundations of democratic debate, trust in science, and respect for knowledge,” Carofiglio said, describing it as an attitude that poisons public discourse and fuels misinformation. On the other hand, he argues that we should embrace conscious ignorance—an intellectual humility that helps us recognize our own limitations while remaining receptive to the knowledge of others. This form of ignorance, like the Socratic “I know that I know nothing,” is the foundation of true competence.

By recognizing that others may hold truths beyond our understanding, we reduce the tendency for categorical statements that exacerbate division. “The truth each of us holds is, for the most part, a legitimate opinion,” Carofiglio explains. “And opinion pushes us to engage in dialogue with others, which is precisely the opposite of polarization.”

Any historian will confirm that stupidity influences the world at least as much as its noble cousins justice and truth, particularly at moments of turmoil. Postel-Vinay talks about the First World War, which he describes as “the result of an enormous concentration of stupidity at the highest levels of European political and military leadership.”

Postel-Vinay points out that even when the lessons of such events appear clear, they are rarely learned. “At the time,” he writes, “stupidity is generally only recognized as such by a minority of observers or actors, who have no influence on the course of events or who, when they have the means to intervene, lack the courage to do so.”

Postel-Vinay notes that, from Europe at least, American society seems to be in the grip of a similar moment. Isaac Asimov once said that “there is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been.” Asimov argued that this ignorance is “nourished by the false notion that democracy means that my ignorance is as good as your knowledge.”

For Carofiglio, the ethical challenge journalists face requires us first to examine how our own personal biases and assumptions affect us. We must examine our own stupidity, as human beings and as journalists. Fact-checking is not truth, and punctiliousness is not rigor.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.