Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Aunohita Mojumdar first encountered Himal Southasian when a writer for the magazine criticized Mojumdar for “failing to ask a single relevant question” in an early 2001 interview with the foreign minister of Bhutan. While working at the Times of India, Mojumdar considered herself a “hard-bitten,” critical journalist. She had even gotten into trouble with the Indian government for her reporting on Kashmir, an area of territorial conflict between India and Pakistan. But when it came to Bhutan, Mojumdar had fallen into the sort of clichéd reporting that Himal—a feisty, Kathmandu-based regional magazine—defined itself by avoiding.

Mojumdar approached Bhutan like a “cute, quaint Dragon Kingdom,” she recalls. When Himal called her out, “I was very embarrassed, but some part of me also felt that they were right.”

Nearly two decades later, Mojumdar has gone from a subject of Himal’s critical reporting to its biggest advocate. As Himal’s editor in chief, she has traversed the subcontinent and moved to Colombo, Sri Lanka, to lead an uphill battle for the “small, gutsy” magazine’s revival.

In 2016, after Mojumdar had been at the magazine for five years, Himal founding Editor Kanak Dixit was arrested, an incident heralded by human rights groups as a sign of the declining state of free expression in Nepal. In the months after, Himal collapsed under bureaucratic pressure. Documents seized from government offices made it impossible to access grant money to run the publication. Visas for its non-Nepali staff were delayed. Payments to outside contributors were held up. It was a slow, silent, insidious kind of media control—not blatant enough to garner international condemnation as a “press attack,” but effective enough to leave the publication completely starved of resources.

From the archives: Resisting press censorship in Nepal

“We were never investigated, we were never questioned, and no permission was ever refused to us,” Mojumdar remembers. “We were just left hanging for a year.”

At the end of 2016, with a grant stuck in indefinite bureaucratic limbo and a zeroed out bank account, Mojumdar had to close Himal’s doors in Kathmandu. Founded on the premise of telling stories from a “regional perspective,” Himal was suddenly forced to reckon with the restrictions of the very nation-state it was made to transcend.

WHEN I ASK DIXIT, who started Himal in 1988 from New York and moved it to Nepal in 1990, how he feels about the magazine’s recent relocation across the Indian subcontinent, he quickly interrupts me. “To begin, don’t call it the ‘Indian subcontinent,’ call it the ‘subcontinent.’ That is exactly what we are trying to do: subvert the narrative from a journalistic platform.”

Historically, India referred to the people of the Indus river, not a boundaried country. “The historical term ‘India’ got hijacked by the nation-state,” Dixit says.

Himal has made a dogged effort to report on South Asia outside of the limiting and relatively new framework of the nation-state. “We’re trying correct a historical wrong by reconnecting people from Balochistan in the far west to the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and even Burma in the east,” says Dixit. “From Tibet or at least the Himalayan region to Sri Lanka. We are giving back their history, an interconnected history, which has been now cut apart by the nation-state boundaries.”

Over its 30 years in operation, Himal has been ahead of the curve, reporting on issues like the Rohingya crisis, Taliban, and militarization of South Asia before they reached the mainstream press. The publication is an alternative to one-dimensional international coverage where, as Shiran Illanperuma, a new senior assistant editor at Himal, puts it, “Sri Lanka is a civil war, Nepal is the Maoists, Afghanistan is the US invasion, and Pakistan is terrorism.”

In Himal, no place is reduced to a single issue, relegated to fluffy travel writing, or rendered a mere pawn in another country’s geopolitical struggle. Reporting on the plastic surgery industry in Afghanistan, the control of the media in the 2018 Maldivian election, the orientalization of Sri Lankan tea advertising, and civil service exams in Bhutan, the magazine upends narratives and steers clear of tropes.

Mojumdar first found a home at Himal as a freelancer with a penchant for off-the-beaten-path reporting. One of two Indian journalists based in Kabul in the mid 2000s, she remembers the Indian media calling her to inquire about the latest bombing or to ask for another story about Pakistan’s role in the conflict. But Mojumdar was interested in what was happening behind the scenes—how banks can be established without communication systems, how telephone lines are constructed in places with land mines, why the maternal mortality rate was killing more than the violence.

“Himal gave me the space and platform to write about the country without the nation-state narrative driven by a country’s interests,” she says. After Himal closed its doors, she devoted a year and a half to recreating that space in a new city.

Even though I may be a citizen of Nepal, my coverage of India should not be overlayed by Nepali nationalism.

THE MONTHS AFTER HIMAL CLOSED were filled with tedious administrative work, bureaucratic gymnastics, and sorting through the results of feasibility studies conducted around India and Sri Lanka. Despite working for long stretches without pay, Mojumdar pushed on. “I knew there was nobody else who was going to do it, so I kind of felt honor-bound to do it,” she says.

Eventually, Mojumdar started splitting her time between her home in Kathmandu and hotels in Colombo, the magazine’s new home. Just four years ago, a magazine like Himal seeking refuge in Sri Lanka would have been unthinkable; to Mojumdar, Colombo was a good, albeit unexpected, fit.

During former president Mahinda Rajapaksa’s time in office from 2005 to 2015, 17 journalists were killed, and many more were abducted and tortured. Several, fearing for their lives, went into voluntary exile from which some still have not returned. But when the government changed in 2015, the new coalition government under President Sirisena promised a freer press environment. While the traumas of the previous administration live on in self-censorship and underdeveloped press establishments, Himal is at least one token of the new government’s promise.

Himal resumed publishing in March of 2018. In a breezy office, tucked away from the congested streets of Colombo’s residential Wellawatte neighborhood, the small team puts out three longform digital pieces a week for an international audience. Imbued with that same old attitude and gutsiness, one piece criticizing the international coverage of the March violence outside of Kandy, Sri Lanka, begins, “If truth is the first casualty of war, then nuance is a frequent casualty of international reporting.”

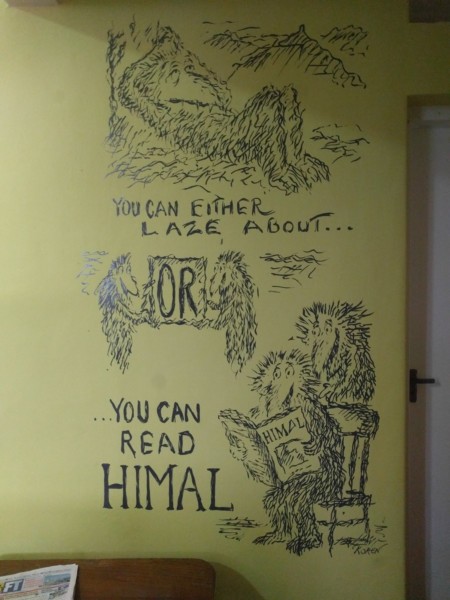

In the entryway of their new office, there is a mural of the cartoon The New Yorker’s Ed Koren made for Himal. “You can either laze about, or you can read Himal,” it says next to a lounging, furry creature.

Courtesy of Himal Southasian

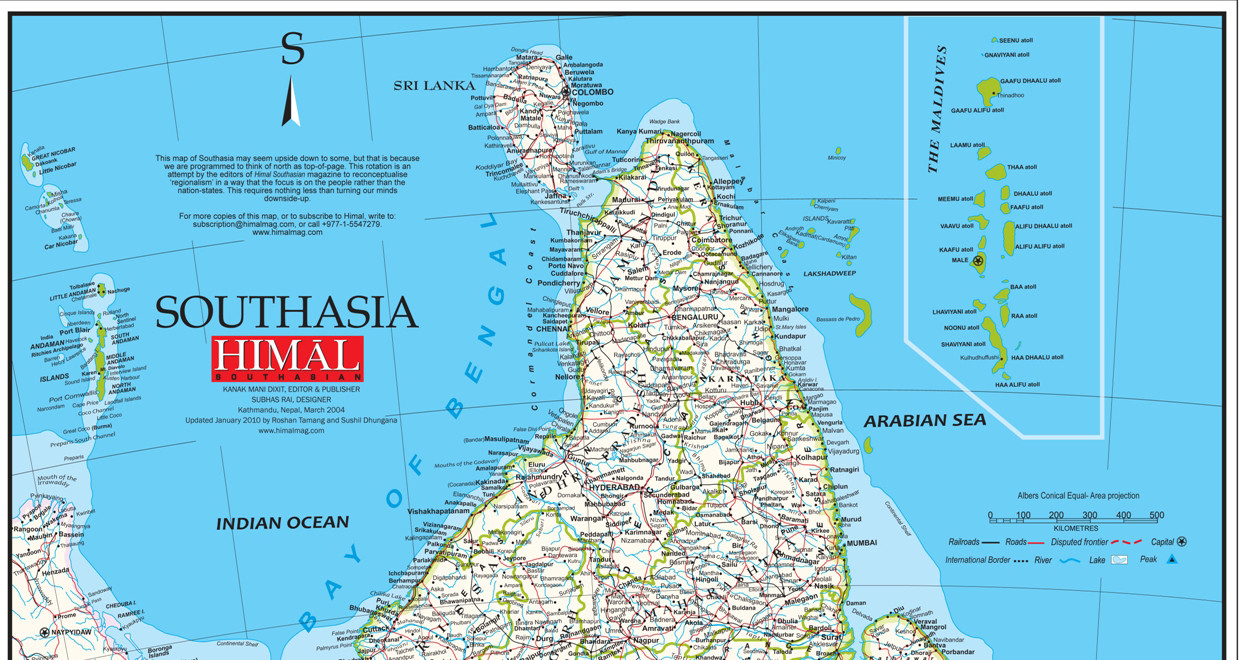

With its boundary-breaking reportage and a style guide full of idiosyncrasies, Himal, at times, feels more like a philosophy than a magazine. In Himal’s vocabulary, the region is “Southasia” not “South Asia.” The former is an entity unto itself, whereas the latter is geographic space defined only by its relation to the rest of the continent. To Himal, I was not an American journalist based in Colombo, but simply a Colombo-based journalist. They do not name writers by nationality. “Even though I may be a citizen of Nepal, my coverage of India should not be overlayed by Nepali nationalism, likewise Pakistani coverage of Bangladesh should not be overlayed by Pakistani nationalism,” Dixit explains.

Hanging on the wall across from the Himal cartoon in the new office is the visual equivalent of these perspective-altering editorial quirks. Dixit’s “right side up” map depicts South Asia flipped, south-side up, with Sri Lanka at the top.

HIMAL‘S PAN-REGIONAL CONTENT may not be affected by location, but the magazine’s continued existence is. In Sri Lanka, press freedom is still precarious. Just a few weeks ago, the nation emerged from months of political turmoil after the President of Sri Lanka unexpectedly appointed former president Rajapaksa as prime minister and ousted the duly-appointed premier Wickremesinghe. The president’s move was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and Rajapaksa ultimately stepped down, but in the wake of the turmoil, threats to the media increased and re-instilled an all-too-familiar feeling of fear in the Sri Lankan press.

Himal’s rebirth in Colombo might have been a sign of improving press conditions in Sri Lanka. However, it is a sign of deteriorating free expression across South Asia that this publication has nowhere else to go. For now, Mojumdar and her team are keen on seizing what she calls a “window of opportunity,” even if it is one that could shut quickly.

From one angle, it may seem Himal has been pushed to the figurative and literal last frontier, to a country on the edge of the earth. But, on Dixit’s “right-side up” map, Sri Lanka looks more like where the world begins.

ICYMI: Media industry turmoil continues as the sharks start to circle

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.