Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

“How can you have, on the front page of your newspaper, written with the guy’s picture: ‘I was forced to drink my own urine’?” asked Mammy Saidykhan, 22, at lunch with friends. Their conversation had spilled over from a morning class at the Media Academy of Journalism and Communication in Gambia, in which they discussed a widely covered story of a political prisoner who was tortured. “Come on,” she continued. “It could have been put in a better way than that. He has kids. He knows people.” Her friends countered—isn’t torture newsworthy?—but Saidykhan was insistent. “I mean, I don’t have a problem with the media reporting it, but it’s the way they’re doing it,” she added. “Of course, you want your paper to sell, but you have to see the people’s plight.”

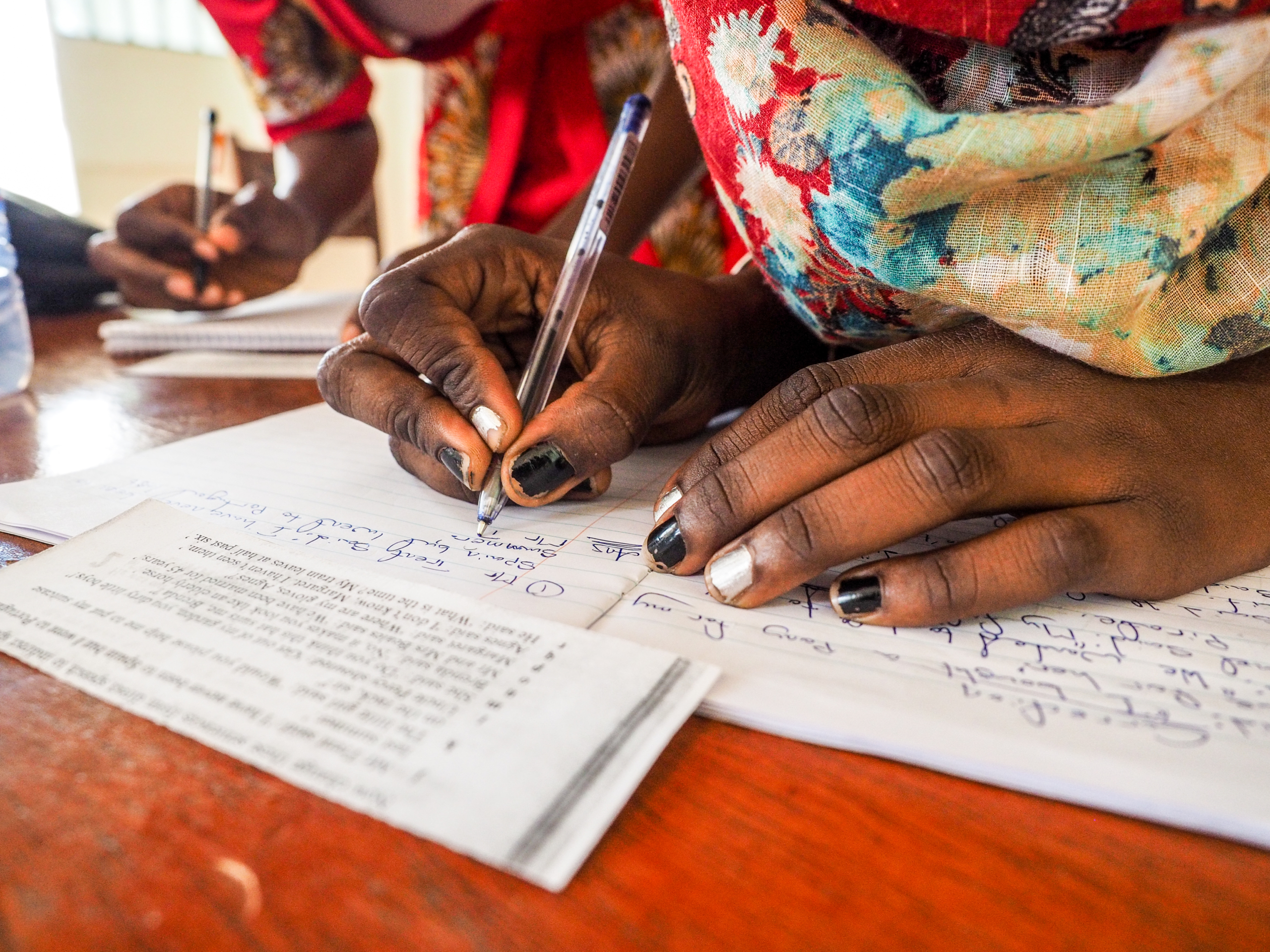

Saidykhan is the youngest student enrolled in the advanced diploma class of the academy, which was founded in 2013 by the Gambia Press Union. In July, she will graduate alongside 20 other journalists, the third class of advanced diploma students in the academy’s history and the first since the ousting of Yahya Jammeh, a dictator who ruled Gambia from 1994 to 2017.

ICYMI: I wrote a story that became a legend. Then I discovered it wasn’t true.

For years, Reporters Without Borders ranked Gambia as one of the worst countries in the world in its global index of media freedom violations. Jammeh has been accused of numerous human rights abuses—torturing political opponents, shooting at demonstrators, and subjecting citizens to a phony “cure” for HIV that led Sarah Bosha, a global health scholar, to call him “one of the great villains of modern times.” He was also known to intimidate, arrest, and even kill journalists.

From the start, the academy was used to operating under threat. “In our first week, we had an issue,” Sang Mendy, the current director of the academy, recalls. A student reported a classmate’s loose political talk to the Gambian intelligence services. “The next day, they came and took the director of the school, and also this guy,” Mendy said. “Eventually, the media was suppressed because not everyone was courageous enough to stand up and speak against the government.”

Since Jammeh’s departure, following defeat in a democratic election, Gambia has risen in the Reporters Without Borders rankings, from 145th out of 180 countries in 2016 to 122nd in 2018. “You can see that people are more comfortable to come to talk about their issues,” Jul Deh Njie, 23, said at lunch. “Now, it’s different.” Saidykhan nodded in agreement.

Their friend Binta Bah, 23, started out as a sports journalist—a safe bet under dictatorship—but has since started covering social justice. “It’s like living the dream that I have always wanted,” she said. “Everything is clear, and you see there is no turning back. And it feels something like a miracle.”

Still, Jammeh’s reign has left scars. “Right now, if you have a younger journalist who wants to specialize in investigative journalism, you look around and you see no one who can actually provide mentorship,” Saikou Jammeh, the secretary of the press union (no relation to the former president), said. Most journalists fled the country years ago, were intimidated into submission, or restricted themselves to rewriting government press releases and flattering the regime.

As a result, the academy has become a crucial pipeline for scores of new media organizations that have opened since Jammeh’s ousting. Students, who often work as reporters part-time, tend to be the most knowledgeable members of their teams, and often some of the only journalists trained in professional standards. The academy drills them on the press union’s code of conduct—which includes guidelines on ethics, accuracy, and how not to editorialize. Reporters are advised not to interview children without the consent of a parent or guardian, double check facts, protect confidential sources, and “ensure that news headlines are fully warranted by the contents of the articles they accompany.”

The academy also offers instruction from foreign reporters. Saidykhan and her friends were taking a class with Pilar Requena, a Spanish television journalist, who led a conversation about how to cover human rights abuses.

“If you speak about the violation of human rights, you won’t get invited to film the jail,” Requena said. “How can you tell the story?”

“You can look at the conditions,” a student in her forties suggested.

“But they won’t let you film,” Requena replied, offering a historical hypothetical. “You are in a dictatorship.”

“We could talk to survivors,” he suggested.

“But they’re afraid to talk.”

A few students rubbed their chins, deep in thought. Saidykhan’s friend Njie had long ago stopped taking notes, and was sitting rapt at the edge of her chair. Requena turned the conversation to the ethics of showing violent images. “If you see people bloody? Is it necessary to film them?” she asked.

“It depends on the need,” a student in his thirties said. “For instance, if there are human rights violations. There is a problem going on in rural areas where people’s hands are chopped off. In that case, you have to show the pictures as they are.”

Requena looked around the class. When no one else responded, she raised the stakes. “Are you respecting the right of a person who is dying after an accident if you are filming him or her? Are you violating their right to die?”

Many in the class shook their heads. After a moment, Njie finally spoke up. “I don’t think that is really right,” she said. “As a journalist, you have to analyze issues. We are there to minimize harm.” She has begun to consider a journalist as not only observer, but a storyteller, someone responsible for molding narratives. “I mean, how would it feel? That, in itself, is a trauma.”

ICYMI: The White House released a troubling video

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.