Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

You learn a lot when journalists pose questions to President Trump.

The insights don’t often come from Trump’s answers, given how frequently he deflects, shades the facts, or lies outright. But we learn a great deal about the reporters doing the interviews.

There are the sycophants, such as Fox News’s Lou Dobbs (“The country owes you a great debt on so much,” he told Trump in 2017) and Maria Bartiromo (“You made a bold decision on Iran, I mean this was incredible,” she told Trump in 2018). And there are the defiant, including CBS’s Weijia Jiang, who sparred with Trump about America’s performance on battling COVID-19 and rebutted his comment about China by responding, “Sir, why are you saying that to me, specifically?”

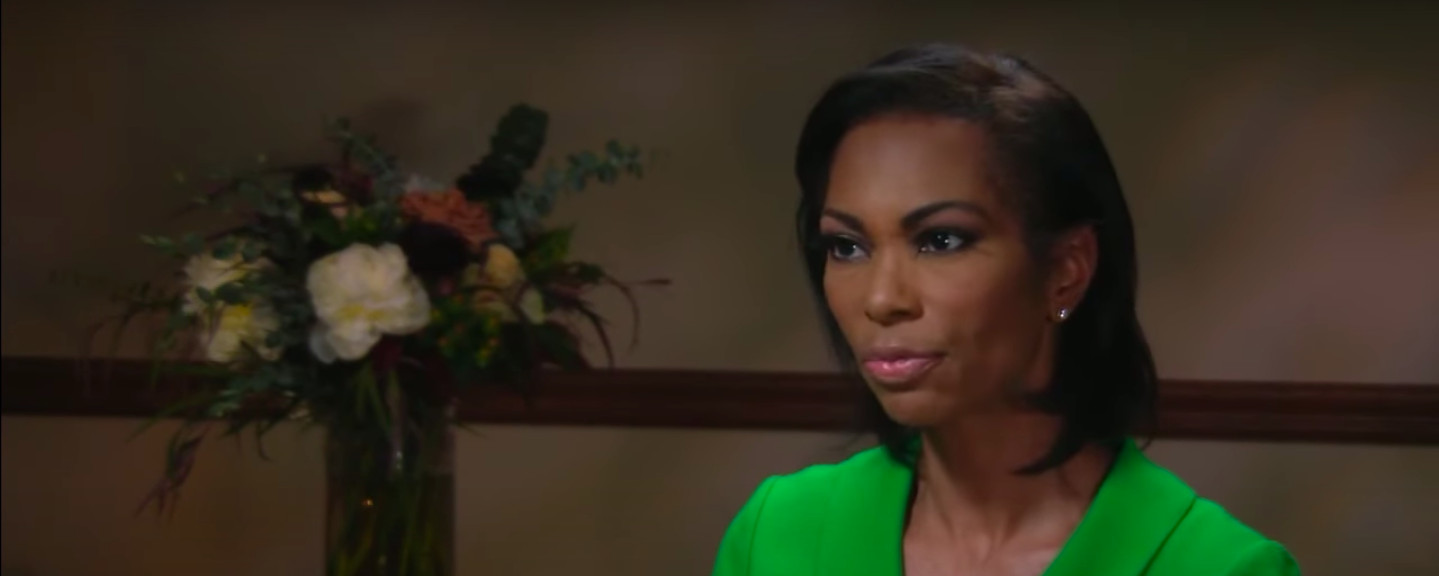

But when Harris Faulkner, a longtime Fox News correspondent and anchor, met with Trump last week, she carved an entirely different path from that followed by many of her colleagues. She was neither antagonistic nor admiring. She put herself into the interview, framed in her roles as a Black woman and a parent, in a way that journalists rarely do with her skill and care.

Faulkner began her twenty-minute interview by asking Trump to place the protests over George Floyd’s death into whatever sweeping context he could muster. Here was her opening question:

You know, Mr. President, with all that’s happened in the last couple of weeks, I feel like we are at one of those historical moments where future generations will look back and they’ll decide who we were. Are you the president to unite all of us? Given everything that’s happening right now?

Trump couldn’t fathom or focus on the question. What will our grandchildren make of this, and of our response? Instead, he floated off into a defense of his administration’s coronavirus performance, eventually winding back to Faulkner’s question. He said:

And then on top of it we had the riots, which were unnecessary to the extent they were. If the governors and mayors would have taken a stronger action, I think the riots would have been…you could call them protesters, you could call them riots…different nights, different things.

A few moments later, Faulkner brought herself into the interview:

I want to talk with you about where we are just in terms of the Black community. People of color.

Faulkner said up front that she knew of the violence and destruction in the aftermath of Floyd’s killing. That was a strategic move, because it boxed Trump out of the excuse that protesters were purely bent on violence. She posed it this way:

You know, I hear you use the word “rioter.” And I understand, we covered it on Fox News. I covered much of that at night as it was bursting a couple of Saturday nights ago. The looting. And it was heartbreaking to see businesses, small businesses, which we know employ north of 66 percent of the people in America. At the same time you had peaceful protesters. And they were hurting.… So I’m curious from you, what do you think the protesters—not the looters and the rioters—we’re intelligent enough to know the difference in our country, right? What do you think they [protesters] want? What do you think they need right now—from you?

Most politicians yearn for such a question and would have an eloquent response ready. But Trump instead responds with the kind of word scramble you’d find in the back pages of a children’s magazine:

So I think you had protesters for different reasons. And then you had protesting also because, you know, they just didn’t know. I’ve watched. I watched it very closely. Why are you here? They really weren’t able to say, but they were there for a reason, perhaps. But a lot of them really were there because they’re following the crowd.

You could argue that Faulkner should have pressed Trump harder, repeating or rephrasing her questions to elicit more relevant answers. We know, though, that journalists rarely get more clarity from Trump on the second go-round. Usually, as CBS’s Jiang and others have found, he becomes defensive, more likely to lash out at the questioner.

Faulkner’s methodical approach has its own power. While the journalism world is becoming embroiled in another internecine debate between those touting “objectivity” versus those criticizing the “view from nowhere,” Faulkner shows how it’s possible to rise above both of those poles with a style that is heartfelt, not maudlin.

The interview drew praise from other journalists. Faulkner “phrased her questions as one human to another, with empathy and respect,” says Cheryl Devall, a longtime radio and print journalist with a string of awards for her work on AIDS and Black America, the 1992 Los Angeles riots and the war on poverty. Trump’s responses, Devall told me in an email exchange, showed that he was “incapable of responding in kind” and were indicative of “his default option to dismiss [journalists’] humanity, legitimacy and commitment to truth.”

At several points in the interview, Faulkner pointed to her own lived experience—as a TV journalist, as a Black woman, and as a mother:

I know from your team, you watched that eight minutes and forty-six seconds of George Floyd. And Mr. President, your response to that is different than a person of color. And I’m a mom. When he called out “Mom” on that tape, it’s a heart punch.

A few moments later, she added:

You look at me, and I’m Harris on TV. But I’m a Black woman. I’m a mom. And you know, you’ve talked about it, but we haven’t seen you come out and be that consoler in this instance. And the tweets. “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.” Why those words?

Faulkner wasn’t just asking Trump why he rehashed this racist phrase. She’s asking the president if he understands how it affects her and millions like her. She is providing him every opportunity to show empathy, or compassion, or kindness.

Trump goes off on a riff, claiming that the phrase comes from former Philadelphia mayor Frank Rizzo—which wasn’t particularly accurate or exculpatory, given that Rizzo attracted support from KKK members and urged his citizens to “vote white.”

Faulkner is prepared for this. She tells Trump:

No, it comes from 1967. I was about eighteen months old at the time.… It was from the chief of police in Miami. He was cracking down. And he meant what he said. And he said, “I don’t even care if it makes it look like brutality. I’m going to crack down—when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” That frightened a lot of people when you tweeted that.

There is much more in the interview, including Trump’s bizarre rant about Abraham Lincoln: “He did good. Although it’s always questionable, you know, in other words, the end result.” Faulkner responds, “Well, we are free, Mr. President.”

Throughout, Faulkner deals with Trump in a way that we don’t often see. She resorts neither to flattery nor to antagonism. She places herself into the interview, but only to get the president to grapple with the pain that the Floyd tape, and Trump’s own words, have inflicted. She gives him every opportunity to put Floyd’s death into the context of the long struggle over civil and human rights. It is an approach, Devall notes, that “journalists have long used, to take the moral temperature of the people they interview.”

That Trump couldn’t rise to the occasion is unsurprising. That a reporter gave him every chance to do so was a revelation.

NEW AT CJR: Maria Ressa’s conviction, and the Philippines’ dire information climate

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.