Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Since the 2016 presidential election, an increasingly familiar narrative has emerged concerning the unexpected victory of Donald Trump. Fake news, much of it produced by Russian sources, was amplified on social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, generating millions of views among a segment of the electorate eager to hear stories about Hillary Clinton’s untrustworthiness, unlikeability, and possibly even criminality. “Alt-right” news sites like Breitbart and The Daily Caller supplemented the outright manufactured information with highly slanted and misleading coverage of their own. The continuing fragmentation of the media and the increasing ability of Americans to self-select into like-minded “filter bubbles” exacerbated both phenomena, generating a toxic brew of political polarization and skepticism toward traditional sources of authority.

Alarmed by these threats to their legitimacy, and energized by the election of a president hostile to their very existence, the mainstream media has vigorously shouldered the mantle of truth-tellers. The Washington Post changed its motto to “Democracy Dies in Darkness” one month into the Trump presidency, and The New York Times launched a major ad campaign reflecting the nuanced and multifaceted nature of truth during the Oscars broadcast in February. Headline writers now explicitly spell out falsehoods rather than leaving it to the ensuing text. And journalists are quick to call out false equivalence, as when President Trump compared Antifa protesters to Nazis and heavily armed white supremacists following the violence in Charlottesville.

ICYMI: What Charlie Rose, Bill O’Reilly, and Glenn Thrush all have in common

At the same time, journalists have stepped up their already vigorous critiques of technology companies—Facebook in particular, but also Google and Twitter—highlighting the potential ways in which algorithms and social sharing have merged to spread misinformation. Many of the mainstream media’s worst fears were reinforced by a widely cited BuzzFeed article reporting that the 20 most-shared fake news articles on Facebook during the final three months of the campaign outperformed the 20 most-shared “real news” articles published over the same period. Numerous stories have reported on the manipulation of Facebook’s ad system by Russian-affiliated groups. Lawmakers such as Senator Mark Warner, a Democrat from Virginia, have been prominently profiled on account of their outspoken criticism of the tech industry, and even Facebook’s own employees have reportedly expressed anxiety over their company’s role in the election.

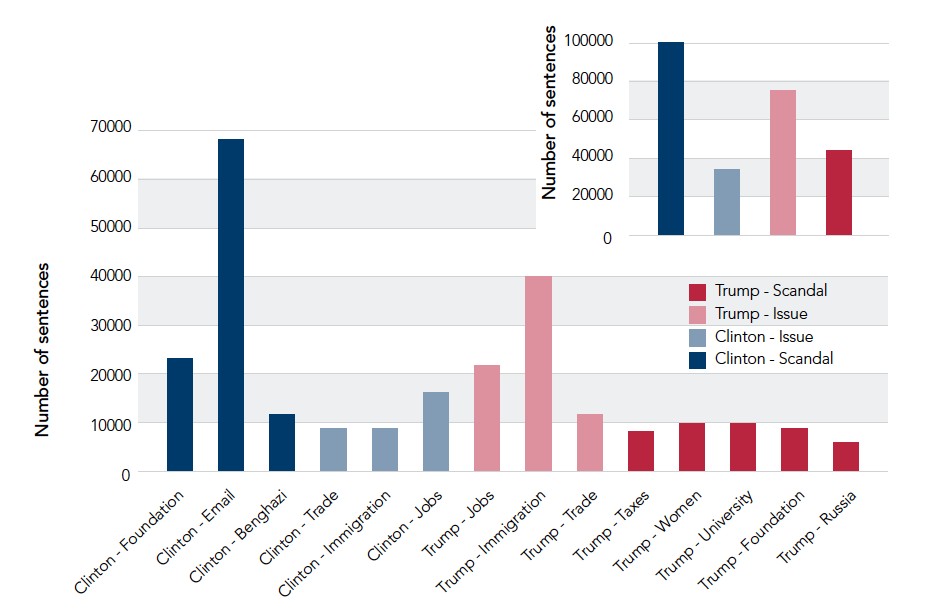

The various Clinton-related email scandals accounted for more sentences than all of Trump’s scandals combined.

We agree that fake news and misinformation are real problems that deserve serious attention. We also agree that social media and other online technologies have contributed to deep-seated problems in democratic discourse such as increasing polarization and erosion of support for traditional sources of authority. Nonetheless, we believe that the volume of reporting around fake news, and the role of tech companies in disseminating those falsehoods, is both disproportionate to its likely influence in the outcome of the election and diverts attention from the culpability of the mainstream media itself.

To begin with, the breathlessly repeated numbers on fake news are not as large as they have been made to seem when compared to the volume of information to which online users are exposed. For example, a New York Times story reported that Facebook identified more than 3,000 ads purchased by fake accounts traced to Russian sources, which generated over $100,000 in advertising revenue. But Facebook’s advertising revenue in the fourth quarter of 2016 was $8.8 billion, or $96 million per day. All together, the fake ads accounted for roughly 0.1 percent of Facebook’s daily advertising revenue. The 2016 BuzzFeed report that received so much attention claimed that the top 20 fake news stories on Facebook “generated 8,711,000 shares, reactions, and comments” between August 1 and Election Day. Again, this sounds like a large number until it’s put into perspective: Facebook had well over 1.5 billion active monthly users in 2016. If each user took only a single action per day on average (likely an underestimate), then throughout those 100 days prior to the election, the 20 stories in BuzzFeed’s study would have accounted for only 0.006 percent of user actions.

Even recent claims that the “real” numbers were much higher than initially reported do not change the basic imbalance. For example, an October 3 New York Times story reported that “Russian agents…disseminated inflammatory posts that reached 126 million users on Facebook, published more than 131,000 messages on Twitter and uploaded over 1,000 videos to Google’s YouTube service.” Big numbers indeed, but several paragraphs later the authors concede that over the same period Facebook users were exposed to 11 trillion posts—roughly 87,000 for every fake exposure—while on Twitter the Russian-linked election tweets represented less than 0.75 percent of all election-related tweets. On YouTube, meanwhile, the total number of views of fake Russian videos was around 309,000—compared to the five billion YouTube videos that are watched every day.

ICYMI: NYTimes editor apologizes after article sparks outrage

In addition, given what is known about the impact of online information on opinions, even the high-end estimates of fake news penetration would be unlikely to have had a meaningful impact on voter behavior. For example, a recent study by two economists, Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow, estimates that “the average US adult read and remembered on the order of one or perhaps several fake news articles during the election period, with higher exposure to pro-Trump articles than pro-Clinton articles.” In turn, they estimate that “if one fake news article were about as persuasive as one TV campaign ad, the fake news in our database would have changed vote shares by an amount on the order of hundredths of a percentage point.” As the authors acknowledge, fake news stories could have been more influential than this back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests for a number of reasons (e.g., they only considered a subset of all such stories; the fake stories may have been concentrated on specific segments of the population, who in turn could have had a disproportionate impact on the election outcome; fake news stories could have exerted more influence over readers’ opinions than campaign ads). Nevertheless, their influence would have had to be much larger—roughly 30 times as large—to account for Trump’s margin of victory in the key states on which the election outcome depended.

It seems incredible that only five out of 150 front-page articles that The New York Times ran over the last, most critical months of the election, attempted to compare the candidate’s policies, while only 10 described the policies of either candidate in any detail.

Finally, the sheer outrageousness of the most popular fake stories—Pope Francis endorsing Trump; Democrats planning to impose Islamic law in Florida; Trump supporters chanting “We hate Muslims, we hate blacks;” and so on—made them especially unlikely to have altered voters’ pre-existing opinions of the candidates. Notwithstanding polls that show almost 50 percent of Trump supporters believed rumors that Hillary Clinton was running a pedophilia sex ring out of a Washington, DC pizzeria, such stories were most likely consumed by readers who already agreed with their overall sentiment and shared them either to signal their “tribal allegiance” or simply for entertainment value, not because they had been persuaded by the stories themselves.

As troubling as the spread of fake news on social media may be, it was unlikely to have had much impact either on the election outcome or on the more general state of politics in 2016. A potentially more serious threat is what a team of Harvard and MIT researchers refer to as “a network of mutually reinforcing hyper-partisan sites that revive what Richard Hofstadter called ‘the paranoid style in American politics,’ combining decontextualized truths, repeated falsehoods, and leaps of logic to create a fundamentally misleading view of the world.” Unlike the fake news numbers highlighted in much of the post-election coverage, engagement with sites like Breitbart News, InfoWars, and The Daily Caller are substantial—especially in the realm of social media.

Nevertheless, a longer and more detailed report by the same researchers shows that by any reasonable metric—including Facebook or Twitter shares, but also referrals from other media sites, number of published stories, etc.—the media ecosystem remains dominated by conventional (and mostly left-of-center) sources such as The Washington Post, The New York Times, HuffPost, CNN, and Politico.

Given the attention these very same news outlets have lavished, post-election, on fake news shared via social media, it may come as a surprise that they themselves dominated social media traffic. While it may have been the case that the 20 most-shared fake news stories narrowly outperformed the 20 most-shared “real news” stories, the overall volume of stories produced by major newsrooms vastly outnumbers fake news. According to the same report, “The Washington Post produced more than 50,000 stories over the 18-month period, while The New York Times, CNN, and Huffington Post each published more than 30,000 stories.” Presumably not all of these stories were about the election, but each such story was also likely reported by many news outlets simultaneously. A rough estimate of thousands of election-related stories published by the mainstream media is therefore not unreasonable.

In just six days, The New York Times ran as many cover stories about Hillary Clinton’s emails as they did about all policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election.

What did all these stories talk about? The research team investigated this question, counting sentences that appeared in mainstream media sources and classifying each as detailing one of several Clinton- or Trump-related issues. In particular, they classified each sentence as describing either a scandal (e.g., Clinton’s emails, Trump’s taxes) or a policy issue (Clinton and jobs, Trump and immigration). They found roughly four times as many Clinton-related sentences that described scandals as opposed to policies, whereas Trump-related sentences were one-and-a-half times as likely to be about policy as scandal. Given the sheer number of scandals in which Trump was implicated—sexual assault; the Trump Foundation; Trump University; redlining in his real-estate developments; insulting a Gold Star family; numerous instances of racist, misogynist, and otherwise offensive speech—it is striking that the media devoted more attention to his policies than to his personal failings. Even more striking, the various Clinton-related email scandals—her use of a private email server while secretary of state, as well as the DNC and John Podesta hacks—accounted for more sentences than all of Trump’s scandals combined (65,000 vs. 40,000) and more than twice as many as were devoted to all of her policy positions.

To reiterate, these 65,000 sentences were written not by Russian hackers, but overwhelmingly by professional journalists employed at mainstream news organizations, such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. To the extent that voters mistrusted Hillary Clinton, or considered her conduct as secretary of state to have been negligent or even potentially criminal, or were generally unaware of what her policies contained or how they may have differed from Donald Trump’s, these numbers suggest their views were influenced more by mainstream news sources than by fake news.

Count of sentences that appeared in mainstream media sources (e.g., The New York Times, The Washington Post, HuffPost, CNN) that were classified as describing either a scandal or a policy issue related to either Trump or Clinton. Reprinted from Rob Faris et al “Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election,” published by the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University.

To shed more light on this possibility, we conducted an in-depth analysis of a single media source, The New York Times. We chose the Times for two reasons: First, because its broad reach both among policy elites and ordinary citizens means that the Times has singular influence on public debates; and second, because its reputation for serious journalism implies that if the Times did not inform its readers of the issues, then it is unlikely such information was widely available anywhere.

We gathered two datasets that captured the Times’s coverage of the final stage of the 2016 presidential election. The first dataset comprised all articles that appeared on the front page of the printed newspaper (399 total) over the last 69 days of the campaign, beginning on September 1 and ending on November 8 (Election Day). The second comprised all of the 13,481 articles published online by the Times over the same period. In both datasets, we first identified all articles that were relevant to the election campaign. We then further categorized each of these articles as belonging to one of three categories: Campaign Miscellaneous, Personal/Scandal, and Policy. Within Personal/Scandal we then further classified the article as focused on Clinton or Trump, and within Policy classified it as one of the following: Policy no details, Policy Clinton details, Policy Trump details, and Policy both details (more details on our methodology can be found here):

- Campaign Miscellaneous articles focused on the “horse race” elements of the campaign, such as the overall likelihood of victory of the candidates, details of intra-party conflicts, or the mobilization of specific demographic groups. For example, an October 12 story with the headline “Republican Split Over Trump Puts States into Play,” which described how Clinton’s campaign was taking advantage of Trump’s battle with the Republican Party. (Note: Hyperlinks point to online versions of the stories described, which were typically published the day before the print versions and may have different headlines) This article was manifestly about the campaign, but treated it mostly as a contest in which a dramatic twist had just taken place. It contained little information that would have helped potential voters understand the candidates’ policy positions and hence their respective agendas as president.

- Personal/Scandal articles focused on the controversial actions and/or statements of the candidates either during the election itself or prior to it, as well as on the fallout generated by those controversies. An example of the former would be an October 8 article “Tape Reveals Trump Boast About Groping Women,” which discussed the infamous Access Hollywood An example of the latter would be an October 29 article, “New Emails Jolt Clinton Campaign in Race’s Last Days,” which discussed the impact of the reopening of a FBI investigation into Clinton’s private email server on the campaign. In addition, we classified each Personal/Scandal article as being primarily about Clinton (e.g., emails, Benghazi, the Clinton Foundation) or Trump (e.g., sexual harassment, Trump University, Trump Foundation, etc.).

- Policy articles mentioned policy issues such as healthcare, immigration, taxation, abortion, or education. Articles coded as Policy No Details mentioned policy issues as impacting the campaign, but did not describe the actual policies of the candidates. For example, an October 26 article, “Growing Costs of Health Law Pose a Late Test” described Donald Trump attacking Hillary Clinton over health premium increases, but did not mention the policy proposals of the two candidates, nor did it note that due to subsidies the hikes would not affect the actual price paid by 86 percent of people in marketplaces. Policy Clinton Details or Policy Trump Details counted articles that mentioned specifics of the Clinton or Trump platforms respectively but not both, while Policy Both Details compared the specifics of the two candidates’ platforms. For example, an October 3 article, “Next President Likely To Shape Health Law Fate,” noted that Clinton had endorsed “a new government-sponsored health plan, the so-called public option, to give consumers an additional choice.” It also noted that “Donald J. Trump and Republicans in Congress would go in the direction of less government, reducing federal regulation and requirements so insurance would cost less and no-frills options could proliferate. Mr. Trump would, for example, encourage greater use of health savings accounts, allow insurance policies to be purchased across state lines and let people take tax deductions for insurance premium payments.”

Of the 150 front-page articles that discussed the campaign in some way, we classified slightly over half (80) as Campaign Miscellaneous. Slightly over a third (54) were Personal/Scandal, with 29 focused on Trump and 25 on Clinton. Finally, just over 10 percent (16) of articles discussed Policy, of which six had no details, four provided details on Trump’s policy only, one on Clinton’s policy only, and five made some comparison between the two candidates’ policies. The results for the full corpus were similar: Of the 1,433 articles that mentioned Trump or Clinton, 291 were devoted to scandals or other personal matters while only 70 mentioned policy, and of these only 60 mentioned any details of either candidate’s positions. In other words, comparing the two datasets, the number of Personal/Scandal stories for every Policy story ranged from 3.4 (for front-page stories) to 4.2. Further restricting to Policy stories that contained some detail about at least one candidate’s positions, these ratios rise to 5.5 and 4.85, respectively.

ICYMI: The story the NYTimes, BuzzFeed didn’t want to publish

The problem is this: As has become clear since the election, there were profound differences between the two candidates’ policies, and these differences are already proving enormously consequential to the American people. Under President Trump, the Affordable Care Act is being actively dismantled, environmental and consumer protections are being rolled back, international alliances and treaties are being threatened, and immigration policy has been thrown into turmoil, among other dramatic changes. In light of the stark policy choices facing voters in the 2016 election, it seems incredible that only five out of 150 front-page articles that The New York Times ran over the last, most critical months of the election, attempted to compare the candidate’s policies, while only 10 described the policies of either candidate in any detail.

Front-page New York Timesstories classified as about the campaign that focused primarily on personal scandals, policy, and miscellaneous matters:

New York Times stories classified in the same manner as above but drawn from the full corpus published at nytimes.com. These figures are qualitatively similar to those cited in a separate Harvard study, by Thomas E. Patterson, based on a broader sample and using a somewhat different methodology.

In this context, 10 is an interesting figure because it is also the number of front-page stories the Times ran on the Hillary Clinton email scandal in just six days, from October 29 (the day after FBI Director James Comey announced his decision to reopen his investigation of possible wrongdoing by Clinton) through November 3, just five days before the election. When compared with the Times’s overall coverage of the campaign, the intensity of focus on this one issue is extraordinary. To reiterate, in just six days, The New York Times ran as many cover stories about Hillary Clinton’s emails as they did about all policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election (and that does not include the three additional articles on October 18, and November 6 and 7, or the two articles on the emails taken from John Podesta). This intense focus on the email scandal cannot be written off as inconsequential: The Comey incident and its subsequent impact on Clinton’s approval rating among undecided voters could very well have tipped the election.

Ten articles on the front page of The New York Times in a six-day period (October 29 to November 3, 2016), discussing the FBI investigation into Secretary Clinton’s use of a private email server. In the same time-period there were six front-page articles on the dynamics of the campaign, one piece on Trump’s business, and zero on public policy of candidates.

Turning now to the policy coverage, arguably no policy issue was more important during the election campaign, or more divisive, than the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare). It is therefore shocking (if not surprising) how uninformed many Americans were about the mechanics of the law or how successful it had been. In early 2017, for example, The Upshot, the data-centric subsection of The New York Times, published two pieces on Obamacare. The first, “One-Third Don’t Know Obamacare and Affordable Care Act Are the Same,” published on February 7, described some important misconceptions about Obamacare held by large percentages of the American public—for example, that almost 40 percent (and 47 percent of Republicans) did not know that repealing Obamacare would cause people to lose Medicaid coverage or subsidies for private insurance. The second, “No, Obamacare isn’t in a ‘Death Spiral,’” published on March 15, 2017, provided readers with some important details about how Obamacare works. For example, it noted that “because of how subsidies work, people were generally shielded from this year’s higher prices.” It also noted that while prices had gone up recently, they “were lower than expected in the first few years of the program.” The article then went on to describe an insurance market that could certainly use improvement, but concluded that the “Obamacare markets will remain stable over the long run, if there are no significant changes.”

These articles provide exactly the kind of analysis that would have helped Times readers understand the state of the ACA prior to the election. In contrast, the Times’s pre-election coverage of Obamacare was surprisingly sparse (we counted only four front-page stories between September 1 and November 8) and surprisingly negative. The first article, on October 3, creates almost the opposite impression of the optimistic post-election articles, stating “Mr. Obama’s signature domestic achievement will almost certainly have to change to survive.” Subsequent articles, appearing over a three-day period from October 25 to 27, were even more negative in tone: “Choices fall in health law as costs rise” declares the October 25 headline; “Growing costs of health law pose a late test;” and finally “Many prefer tax penalties to health law.” All four articles emphasized troubles in the insurance market, failing to mention that most policyholders have subsidized capped prices (and are therefore insulated from premium hikes), or that the government was spending less than anticipated, or that premiums were rising slower than before Obamacare. None of the articles mentions the Medicaid expansion, one of the most popular parts of the bill.

All four front-page articles that touch on the Affordable Care Act (aka ObamaCare), published on (from left to right) October 3, 25, 26, 27.

Consistent with other studies of media coverage of the election, our analysis finds that The New York Times focused much more on “dramatic” issues like the horserace or personal scandals than on substantive policy issues. Moreover, when the paper did write about policy issues, it failed to mention important details, in some cases giving readers a misleading impression of the true state of affairs. If voters had wanted to educate themselves on issues such as healthcare, immigration, taxes, and economic policy—or how these issues would likely be affected by the election of either candidate as president—they would not have learned much from reading the Times. What they would have learned was that both candidates were plagued by scandal: Hillary Clinton over her use of a private email server for government business while secretary of state, as well as allegations of possible conflicts of interest in the Clinton Foundation; and Trump over his failure to release his tax returns; his past business dealings; Trump University; the Trump Foundation; accusations of sexual harassment and assault; and numerous misogynistic, racist, and otherwise offensive remarks. What they would also have learned about was the ever-fluctuating state of the horse race: who was up and who was down; who might turn out and who might not; and who was happy or unhappy with whom about what.

To be clear, we do not believe the the Times’s coverage was worse than other mainstream news organizations, so much as it was typical of a broader failure of mainstream journalism to inform audiences of the very real and consequential issues at stake. In retrospect, it seems clear that the press in general made the mistake of assuming a Clinton victory was inevitable, and were setting themselves as credible critics of the next administration. Possibly this mistake arose from the failure of journalists to get out of their “hermetic bubble.” Possibly it was their misinterpretation of available polling data, which showed all along that a Trump victory, albeit unlikely, was far from inconceivable. These were understandable mistakes, but they were still mistakes. Yet, rather than acknowledging the possible impact their collective failure of imagination could have had on the election outcome, the mainstream news community has instead focused its critical attention everywhere but on themselves: fake news, Russian hackers, technology companies, algorithmic ranking, the alt-right, even on the American public.

To be fair, journalists were not the only community to be surprised by the outcome of the 2016 election—a great many informed observers, possibly including the candidate himself, failed to take the prospect of a Trump victory seriously. Also to be fair, the difficulty of adequately covering a campaign in which the “rules of the game” were repeatedly upended must surely have been formidable. But one could equally argue that Facebook could not have been expected to anticipate the misuse of its advertising platform to seed fake news stories. And one could just as easily argue that the difficulties facing tech companies in trading off between complicity in spreading intentional misinformation on the one hand, and censorship on the other hand, are every bit as formidable as those facing journalists trying to cover Trump. For journalists to excoriate the tech companies for their missteps while barely acknowledging their own reveals an important blind spot in the journalistic profession’s conception of itself.

We have no doubt that journalists take seriously their mission to provide readers with the information they need in order to make informed decisions about matters of importance. We note, however, that this mission implicitly assumes that journalists are passive observers of events rather than active participants, whose choices about what to cover and how to cover it meaningfully influence the events in question. Given the disruption visited upon the print news business model since the beginning of the 21st century, journalists can perhaps be forgiven for seeing themselves as helpless bystanders in an information ecosystem that is increasingly centered on social media and search. But even if the news media has ceded much of its distribution power to technology companies, its longstanding ability to “set the agenda”—that is, to determine what counts as news to begin with—remains formidable. In sheer numerical terms, the information to which voters were exposed during the election campaign was overwhelmingly produced not by fake news sites or even by alt-right media sources, but by household names like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and CNN. Without discounting the role played by malicious Russian hackers and naïve tech executives, we believe that fixing the information ecosystem is at least as much about improving the real news as it about stopping the fake stuff.

Methodology

Analysis of front pages

Every front-page article was read by two researchers and coded for the three topline categories and their subcategories, using only the text that appeared on the actual front page (not on what may be continued on future pages). There was very little disagreement between the two researchers; for example, both researchers coded the same set of articles as covering policies of both candidates, and disagreed on only one article with respect to coverage of policy. For simplicity, the authors reviewed all disagreements together, by hand, and we reported from that dataset.

Analysis of the full corpus

What The New York Times puts on the front page of its print edition is important, but not necessarily representative of how many readers encounter the news, either because they navigate directly to individual articles from social media sources (mostly Facebook and Twitter), or because articles at nytimes.com can appear in different places at different times. To verify that our conclusions regarding coverage of the campaign on the front page was not totally unrepresentative of the paper as whole, we also coded the entire corpus of all articles published on nytimes.com during the same period. Because this sample is much larger (13,481 vs. 399), we coded them using a combination of machine classification and hand coding.

- First, we scraped the headline and first paragraph, if provided by the API, for each Times article from September 1 through November 9, 2016, using the archive API for all articles that included the words “Clinton” or “Trump.” Note: This criterion included virtually all campaign-related articles, but may have also included potentially non-campaign related articles (e.g., about Bill Clinton or Ivanka Trump).

- Next, we compiled a list of words (details below) delineating three categories of article: Campaign (focused on the horse race and how people react to events); Policy (focused on a policy issue); and Personal/Scandal. For each article, we checked if any of the words in the article began with one of the stems in our word list. For example, if an article contained the word “immigration,” we would first notice that it starts with “immigrat,” which is one of our policy words; thus we would mark it as a Policy article. For all articles marked as Policy, we then hand-coded them into the four subcategories and tossed articles into Campaign Miscellaneous if they did not actually cover any policy.

- Finally, we hand-coded the Policy articles as Policy No Details, Policy Clinton Details, Policy Trump Details, or Policy Both Details using the same criteria as above.

Word list for Clinton/Trump categories:

- Clinton Personal/Scandal words: email, benghazi, foundation, road

- Trump Personal/Scandal words: russia, foundation, university, woman, women, tax, sexual assault, golf, tape, kiss

- Policy words for both candidates are taken from the list of issues covered by On the Issues: abortion, budget, civil rights, corporation, crime, drug, education, energy, oil, environment, family, families, children, foreign policy, trade, reform, government, gun, health, security, immigra, technology, job, principl, value, social security, war, peace, welfare, poverty, econom, immigrat, immigran

- Campaign words for both candidates: fundraise, ads, advertisements, campaign, trail, rally, endors, outreach, ballot, vote, electoral, poll, donat, turnout, margin, swing state

ICYMI: Explosive BuzzFeed scoop raises eyebrows

A version of this paper will be presented at “Understanding and Addressing the Disinformation Ecosystem,” a conference to be held December 15-16, 2017, at the University of Pennsylvania Annenberg School of Communication, organized by Claire Wardle and Michael Delli Carpini and sponsored by the Knight Foundation. The authors are grateful to William Cai for valuable research assistance, and to Yochai Benkler and Matt Gentzkow for helpful comments and corrections.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.