Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Clay Johnson’s 2013 book, The Information Diet, lamented the state of people’s news and media habits in the digital age. In it, he compared online users’ media consumption to the obesity epidemic—we consume too little that is good for us and too much fatty, substance-less content—and laid out his “case for conscious consumption.”

Four years later, our information diets are just as bad, or even worse. Johnson reports he’s routinely contacted by readers who say his messages resonates. I recently conducted an informal survey among friends, and its results confirm what Johnson is hearing: User dissatisfaction with news consumption stems in part from bad habits.

While that may be bad form on the part of readers, publishers have also failed to realistically consider how they might promote regular, healthy media habits now that watching the nightly news is a quaint, bygone ritual. As publishers have ceded the news-habit high ground, another entity has, of course, captured it eagerly: Facebook. Users check their phones hundreds of times a day, and, as we know all too well, over half of American adults get their news from Facebook.

So how might news publishers recapture information habits from Facebook and create a more elevated, productive public discourse? New research into how people build habits, and thriving technologies around them, could help point the way. Devices like Fitbit and apps like iPhone Health are helping users improve exercise, sleep, and eating habits. Publishers might even take some pointers from Facebook itself.

How hard is it to change?

Some of the key research into online habits comes from Nir Eyal, author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. He suggests taking a clear-eyed view of just how difficult or simple it will be to break or create desired behaviors.

According to Eyal’s “Behavior Change Matrix,” usage of Facebook would fall in the bottom right “Addict” quadrant; that is, a behavior that’s desired to break and that requires a high level of self control to change it. News reading would ostensibly fall in the top left, “Amateur” quadrant—desired behavior with a low level of self control required to cultivate it.

RELATED: How to establish a media diet

To expect users to simply “quit” Facebook through sheer force of will when it’s an addict level behavior is unrealistic (and the reason resolutions to quit smoking cigarettes so often fail). The best way to account for that difficulty, Eyal suggests, is to offer users some reward or intervention that gives them the boost they need. This, at the same time, could be harnessed to promote the “amateur” behavior that’s desired (more conscientious reading of trusted sources).

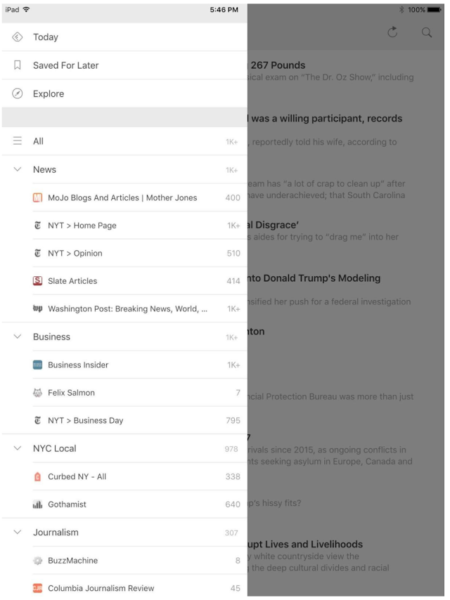

RSS, or Real Simple Syndication, is an example of a news-reading tool that requires a high level of self control to use, as it offers no rewards beyond the content. RSS allows users to subscribe to feeds from outlets of their choosing, and then receive the stripped down text of articles in one centralized place (a RSS reader, like Feedly). Users visit the app when they want to check in on what has come through. With RSS, you can be sure you are seeing all of the content from any outlet. Interestingly, in the survey I conducted, the highest level of satisfaction with news habits came from people who use RSS.

Finding the core motivator

Eyal posits that digital habits stick when they meet some deep human need, or core motivator. Publishers and news innovators should research the deeper reasons behind why users engage with their products, though some research into why people consume news, at the core, already exists. (Those reasons include entertainment, escape, “it might affect me,” curiosity, sense of civic responsibility, appearing in the loop.)

Once core motivators are understood, digital products can be built around them. For example, when designing a company intranet for a global bank, research may reveal that employees feel out of the loop from the goings on at the company’s main office. Their core need is, therefore, feeling included. So a digital product could be built with a back-and-forth communication stream between the home office and users in outlying offices. Similarly, if users revealed that “appearing in the loop” was their main motivator behind reading news, a digital product could be built around the concept of easy-to-share thoughts and must-know ideas.

Intervening at the moment of weakness

One proven method for breaking bad behavior and diverting it to other activities, both in real life and in the digital space, is intervening at the moment it’s about to take place. The addiction app, Triggr, collects user data around the behavior of long-time drug addicts. Based on sleep, text, and other patterns, the app can predict if the user is about to relapse and engage in the “Don’t” behavior desired to break. At that moment, it can intervene with a call or visit from a human counselor. A news-reading app could similarly intervene when users are about to scroll through Instagram or Facebook for the 50th time in a day, offering a tidbit of news to divert attention away from the scrolling action.

“Intervening” in users’ existing streams of consumption is something many outlets are trying. Quartz has created an app that mimics a text message conversation. Purple delivers political news through Facebook Messenger. And of course, most news outlets now publish to Facebook and other social media outlets.

Offering rewards

The key difference between health habits and digital ones, of course, is that developing physical health habits offers tangible, “real world” rewards like losing weight or not relapsing. The rewards of digital habits are confined to the world of the screen. So, Eyal suggests, an app must offer digital rewards to encourage use. He cites a few of them: rewards of the hunt (searching through photos online and finding a treasure) and variable rewards (the app provides surprising or novel rewards each time it’s used). Game-ification—competition with oneself or others—is another of the key rewards that can keep users coming back to a digital product. Measuring steps through Fitbit or iPhone Health provides users with “scores” to track (Lord Kelvin famously said, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it), and then allows users to beat their scores or those of friends. The cooperation involved in group gaming can be so powerful that a gamer’s brain mirrors that of a heroine addict when they’re booting up or getting ready for a fix.

TRENDING: A hidden message in memo justifying Comey’s firing

And then there’s one of the most powerful rewards: “rewards of the tribe,” or social rewards. That’s the very reward Facebook and other social networks use to maintain such a powerful pull on users that they fall into unhealthy digital habits. But could that same powerful pull be harnessed for the desired behavior in question here—deeper and more consistent news reading of trusted sources?

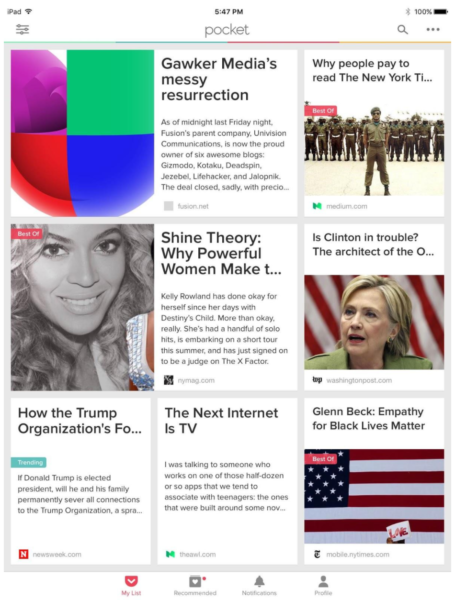

As people go about their day, they may encounter articles they wish to read but simply don’t have the time at that moment. By allowing users to save the articles for later in one centralized location, apps like Pocket and Instapaper help users cope with the deluge. Importantly, they offer two of Eyal’s key rewards: “The rewards of the hunt” (searching for value) and an investment in building up value in the app over time by creating a repository of desirable articles that can be tagged and organized. Recently, Pocket has also begun integrating the “rewards of the tribe,” a social feature to share recommendations with friends.

The most powerful habit hack of all

There are biological reasons that social signals (those little notifications on social networks that we’ve received a “like”) are irresistible to humans. As Paul Atchley, professor of psychology at Kansas University, who has studied online habits, explains, a large part of the human brain is dedicated to social cues, allowing us to both dominate the food chain, and cooperate in groups without killing one another. Humans, he says, are “cooperative super predators,” all because our brains care greatly about being accepted by others. It’s that part of the brain that is activated when we collaborate successfully on a project (or, in an earlier era, on a hunt). It’s that same part of the brain that is activated when we receive signals on our social networks, releasing dopamine to keep us hooked on the behavior.

So, Atchley says, some of the most powerful “brain hacks” are around social signals. For instance, Eyal himself was trying to build an exercise habit, but was only able to do so when he began using an app that gave him feedback from an online community. Because we are hardwired to be social animals, these signals are powerful and extremely difficult to resist.

So, could we use this most powerful of habit hacks to break the overreliance on Facebook for news? Could we harness social signals to receive news through other means—perhaps designing the social pull on a new platform, say, even better than Facebook has? Perhaps, but Atchley warns to proceed with caution. The emotional “lizard brain” fulfilled via social habit triggers may be in direct opposition to the more sustained, mindful focus required for deep news reading and critical thought. Atchley says: “You may get people to care about accessing news if it’s about emotions. Look at what happens every four years. I get highly addicted to a few blogs because I am worried about the outcome of the election. But when it’s over, it’s less interesting to me. That emotional content is not something the news can always convey, nor should it always convey it.” He worries that habit hacks, such as the ones Eyal espouses, are shortcuts that may work for going on a run but won’t work for mentally focused tasks like news reading.

TRENDING: Eleven newsletters to subscribe to if you work in media

It’s important to note that different users have different needs and proclivities. While some will need emotional triggers to sustain a digital behavior, others may indeed able to go on a media diet through sheer force of will. There are also socioeconomic considerations: Users with time and resources to examine these issues may seek news alternatives, but those struggling financially or otherwise might default to the easiest option before them and could need more pointed interventions. Regardless, Facebook’s monopoly on delivery means less variety for users, and clearly more alternatives are needed.

Something users want

One upside to this challenge is that many users recognize their digital content consumption habits are not healthy and want help.

This is good news for publications because it means there is an actual user problem in need of solving. For all that’s been written about the woes of news in the internet era — failing business models for newspapers, the battle between platforms and publishers, loss of revenue from ad blockers —precious little attention has been paid to the woes of the user/reader/listener/watcher and how those might be connected to the woes of publishers.

ICYMI: 11 images that show how the Trump administration is failing at photography

At a higher level, the situation is in fact quite serious: Since users spend so much time in one place controlled by a single algorithm that optimizes content just for them, citizens of the same country or even neighborhood essentially inhabit alternate digital realities (as the WSJ’s Red Feed/Blue Feed aptly demonstrates). And, because that algorithm is vulnerable to ad dollars, users are susceptible to behavior manipulation on a massive scale by commercial interests, political actors, or even foreign governments.

In one optimistic outcome, perhaps traditional news outlets could come together and put their collective efforts into a habit solution for news that would truly challenge social platforms, presenting an alternative revenue source for publishers in the face of monopolized power. As a bonus for their efforts, we’d all get something we sorely need —healthier news habits and an elevated public discourse.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.