Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Days after the second swearing-in of Donald Trump, Jeremy Scahill, a founder of Drop Site News, an accountability journalism Substack, sent a fundraising email to readers. “New president, same war crimes,” the subject line read. Much of the American press was focused on Washington, but Drop Site would be directing its attention to Gaza, he wrote, “documenting Israel’s crimes, which are facilitated by the US government, and ensuring perpetrators face justice.” He promised reporting on Trump and Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, as well as dispatches from Palestinian journalists on the ground. Underlying the message was a sense that the new administration might not be as consequential on the world stage as the flood of reporting suggested.

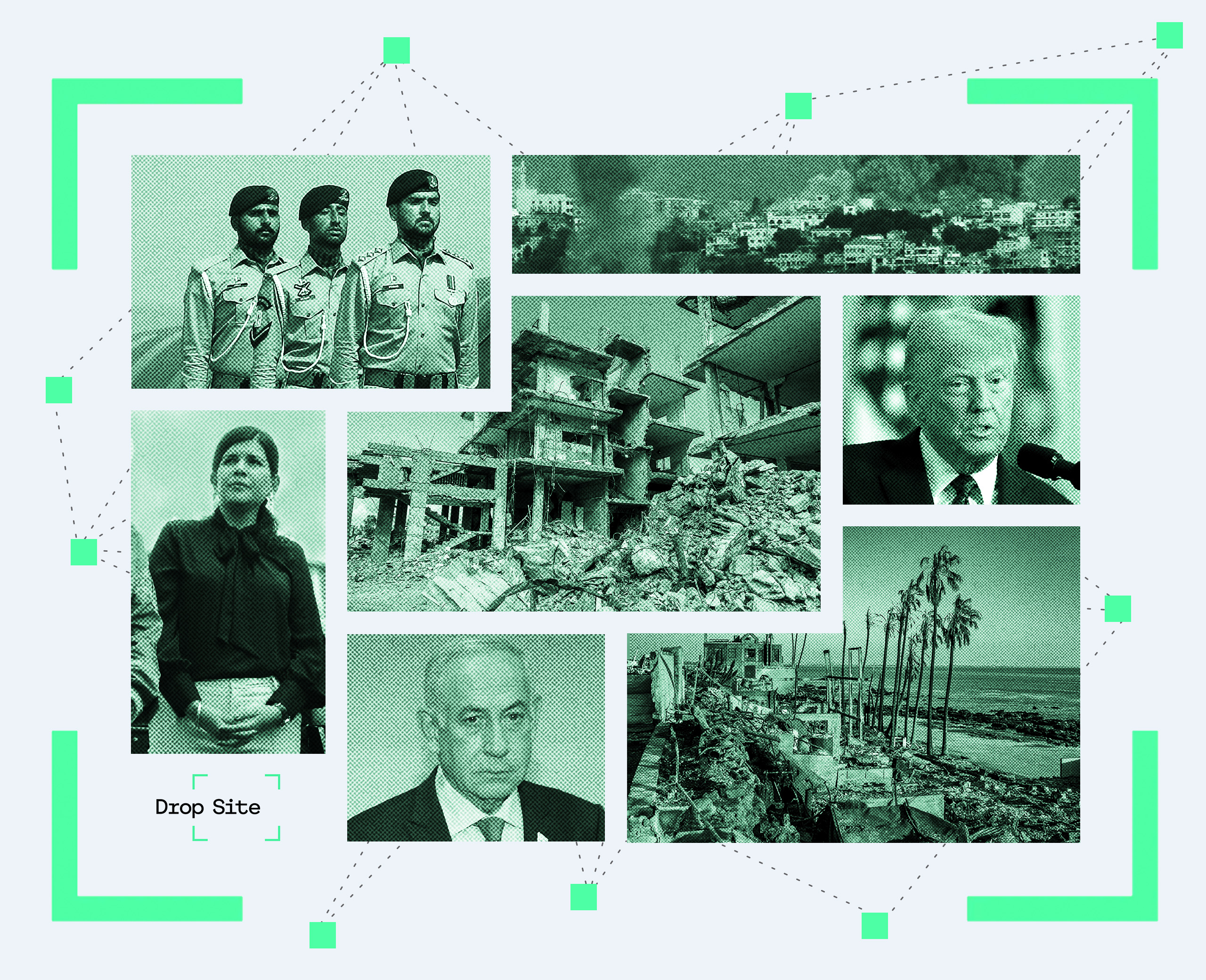

Drop Site debuted in July, a project of Scahill and two former colleagues from The Intercept, Ryan Grim and Nausicaa Renner, with the aim of giving voice to people and viewpoints “otherwise shut out of the American conversation,” Grim told me. Coverage would examine “power and greed”—not of the #resistance variety, which centered on the singular threat of Trump, but zoomed out, tracking nefarious uses and abuses of power on a global scale. In the months since, the team has brought on a few other writers and support staff, totaling eight people, all of them working remotely. “Drop Site will cover the Democrats as critically as we will cover Republicans—we’re not going to change depending on who’s in power,” Sharif Abdel Kouddous, the Middle East and North Africa editor, told me. “Our ethos is adversarial journalism.”

That was clear from the start: among the first stories on Drop Site was a set of interviews with Hamas officials, two of them on the record. “Some people will inevitably criticize the choice,” Scahill wrote at the start of the piece. “I believe it is essential that the public understand the perspectives of the individuals and groups who initiated the attack that spurred Israel’s genocidal war—an argument that is seldom permitted outside of simple sound bites.” It’s simply a matter of presenting the facts, the logic went. “It’s pretty obvious if there’s a conflict between two sides, and you’re covering the conflict, you speak to the different sides of the conflict,” Grim told me. “That’s just Journalism 101.”

That’s not to say that Drop Site foregrounds every perspective—beyond asking the Israeli military, say, for comment on stories, the editors don’t seek more out—or that they won’t reach beyond the boundaries of traditional journalism. Drop Site waged a campaign to make a book by Refaat Alareer, a slain Palestinian poet, a bestseller, and started a petition to release Dr. Hussam Abu Safiya, the director of a hospital in Gaza, from Israeli custody. (“Dr. Safiya is a source in Gaza we were in touch with very regularly,” Renner said. “We had seen almost daily videos of his work with patients in the hospital. Speaking up about his abduction was a natural extension of the reporting he helped us to do.”) Investigations—for instance, into the US government’s backing of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project—err on the side of raising concerns rather than granting benefit of the doubt; skepticism is a guiding principle. “All US government funding—especially at this scale—deserves journalistic scrutiny,” Renner told me.

That sensibility is something of an extension of the founders’ experience at The Intercept—which, in recent years, has gone through a series of changes of the guard, budget cuts, and internal disputes. When Grim and Scahill announced their departure, they did so via an email newsletter, under the banner of both outlets and sent to Intercept readers. (That was a function of a financial exit agreement, not an indication of an amicable splintering-off.) Though their coverage often overlaps, Drop Site aims to distinguish itself with an international bent: investigations on military overreach in Pakistan, including a secret online army operation (which led to Drop Site being banned in the country); reporting on Ecuador’s attorney general allegedly using her office to pursue politically motivated cases; a profile of a journalist reporting in Gaza.

Not every story is about a conflict zone; Drop Site has also covered the Los Angeles fires. Nor is all the reporting done in-house. “We don’t want to do parachute journalism,” Renner told me. Kouddous works with a number of reporters in Gaza. “We’ve been through a period in the Arab world where decades are happening in days,” he said. Lately, he has brought in a piece by Hossam Shabat, a Palestinian journalist, on a “mass expulsion campaign by the Israeli military in Beit Lahia that forced thousands of Palestinian families to flee,” and reporting by Abubaker Abed on the cash crisis in Gaza, as people are bartering their belongings for food. Abed, who until recently had been a soccer commentator, identifies as “an accidental war correspondent”; he has published several stories with Drop Site. “He is a local, from the community, and is organically embedded,” Murtaza Hussain, a Drop Site reporter, said. “He knows the people who are being affected by the war—he’s living with them.” All of Drop Site’s coverage is based on reporting. “There’s really no value in opinion anymore,” Grim told me. “You can get it for free anywhere on social media, on any platform.”

That formula has enabled Drop Site to amass more than three hundred thousand subscribers. Most have signed up for the free version; about nine thousand have opted in to monthly and annual rates (twelve or ninety-nine dollars, respectively), which come with perks (commenting ability, virtual and IRL events). Some attain “hero” status, at two thousand dollars a year, which comes with signed books from Scahill and Grim, as well as a call with both. Subscribers and individual donors account for a bit more than half of Drop Site’s revenue; the rest comes from foundation grants. Renner (a former CJR editor) describes Drop Site’s target audience as “American readers who have politically heterodox opinions and people in English-speaking diaspora communities around the world.”

Social media doesn’t drive much traffic. On X, Drop Site’s approach has been to use the platform mainly to highlight reporting from other sources. “It becomes a kind of refined news service in a way,” Kouddous said. “We summarize what’s happening, for example, in North Gaza today in a thread, and it could include reporting from Al Jazeera, AP, our own sources on the ground who are constantly giving us updates that we can’t necessarily use in a story.” Looking ahead, Renner noted, they would like to expand their reach to younger audiences through vertical videos.

In 2017, Trump’s arrival in Washington drove wide attention to news outlets, but Drop Site isn’t counting on that. “Obviously, we have a different administration with different political ideologies coming in—and yeah, we’ll take that into account,” Kouddous told me. Still, he said, Drop Site’s approach to coverage won’t change. “I think that a lot of outlets that we’ve seen over the last decade or so—when Trump came into office, he was much more belligerent towards the media, and so we saw the media then kind of stand up to power more. And you had ‘Democracy dies in darkness,’ and all this. Perhaps Trump does pose a different kind of threat to freedom of the press. But the Democrats’ foreign policy and also domestic policy are not held to account in the same way.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.