Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Over the weekend, at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn Bridge Park, Maria Salazar Ferro, director of the emergencies department at the Committee to Protect Journalists, walked through a series of final memories. CPJ, in collaboration with United Photo Industries, had put on a “Journalists Under Fire” exhibit as part of the park’s annual Photoville festival. “Photojournalists have to work on the front lines—they can’t shoot from a hotel room,” she said. “So that puts them at heightened risk.”

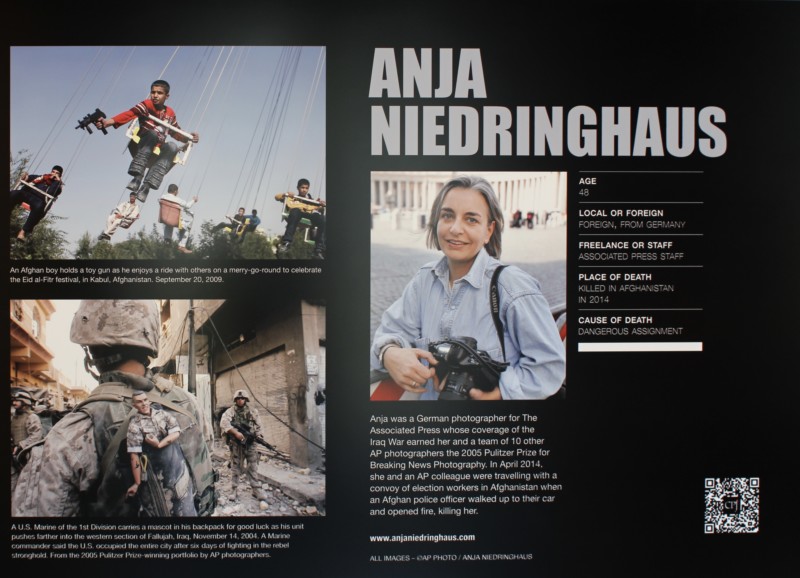

Inspired by CPJ’s book and digital campaign The Last Column, which highlights the final articles and photographs of fallen reporters, the St. Ann’s show displays work by ten photojournalists, all of whom have been killed, jailed, or threatened. Organized as an array of profiles, the exhibit features images by each photographer alongside a personal shot, putting a face to each story.

There’s Mohamed Ben Khalifa, a thirty-five-year-old Libyan photojournalist, and his portrait of an honor guard in silhouette, a burst of light glowing behind him. Next to that is another photo by Khalifa, featuring three men in a bunker dug out of red dirt. They’re Libyan soldiers recovering from clashes with militants on the front line in Al Ajaylat, seventy-five miles west of Tripoli. Khalifa was killed by cross fire while covering similar clashes in Tripoli on January 19, 2019.

Then there’s Anja Niedringhaus, a forty-eight-year-old German photojournalist, pictured with a smile, camera in hand, wearing a light denim shirt. In Iraq, where she covered the war in 2005 as part of a Pulitzer Prize–winning team of Associated Press photographers, she captured the image of a US Marine carrying two of his unit members, one over each shoulder; in focus is a toy soldier the Marine had attached to his backpack for good luck. In Afghanistan, Niedringhaus photographed a group of boys, suspended in midair on a merry-go-round against a blue sky; the base of the structure is out of frame, and they appear to be flying; one of the boys points a toy gun at the ground. In April 2014, Niedringhaus and an AP colleague were traveling with a convoy of election workers in Afghanistan when a police officer walked up to their car and opened fire, killing her. “We wanted to show stories of local photographers who are less known at an international level,” Salazar Ferro said. “We also wanted to look at different issues, like women photographers—Anja’s story in particular, because there are actually very few women photographers who have been killed.”

In addition to the photojournalists’ profiles, the exhibit includes data visualizations about journalist safety, including the total number of photojournalists who have died in the field since 1992 (161), the number in jail (32), and the number missing (7). Visitors can interact with computers stacked with CPJ data. Salazar Ferro pointed out that, based on a 2018 CPJ survey of roughly five hundred journalists, 90 percent have worked in high-risk environments, and 75 percent have worked in places without adequate safety equipment or a formal risk-assessment plan. “We’re trying to get people to understand the price, which is often a life, that getting that story out can cost,” she said.

On Sunday, Salazar Ferro hosted a panel at St. Ann’s, “Teargas, Trolling, and Trauma: Photographing Political Polarization in the U.S.” To a packed crowd, she explained that, of the photojournalists who have been killed on the job, about half have fallen to cross fire. “This number is particularly distressing when you compare it to all other types of journalists, about 22 percent, who have been killed in cross fire,” she said. “So you see how many more photographers are killed in these situations. But we believe it could be prevented with the appropriate safety measures.” Editors need to be mindful of these risks, she went on: “It needs to be something that is always in the foreground for our community.”

Ryan Christopher Jones, a panelist who contributes to outlets such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal, said that in recent years, newsroom budget cuts have pushed more and more people into freelancing, which in turn increases the likelihood that photographers, desperate for a paycheck, will get themselves into risky situations. “The rise in freelance journalism means more competition, and more competition means freelancers are more likely to take on risks,” he explained.

For many viewers, the exhibit was humbling. After the event, M.M. Scott, who had wandered in without knowing what to expect, said she received an education. “I’m just astounded at the number of journalists killed in the line of duty and how much we don’t know about it,” she said. “I just really have a deep admiration for those who put themselves in the cross fire for the sake of helping others and getting others’ stories out.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.