Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

In the story of the novel coronavirus, there are two viruses: the virus as it really exists and the virus as we understand it. The former changes rarely. The latter is changing all the time.

Vivian Wang, a reporter for the New York Times, first read about the novel coronavirus in the South China Morning Post newsletter, sitting at her parents’ kitchen table in Chicago at the end of her holiday break, in January. “Nobody really knew what was going on; the seafood market was being shut down. I just remember reading it and thinking… this seems pretty crazy,” Wang says. Days later, she flew to Hong Kong.

Though Wang was planning to move to Hong Kong, her January trip was temporary, so she could attend a few meetings. On January 6 she wandered into the office and sat in on the morning editorial meeting. The team was discussing the virus and the reporting out of China.

“I think we should look into it,” Wang remembers her colleagues saying. “It might turn out to be nothing—but if it does turn out to be big, we want to make sure that we’ve been covering it from as early on as possible.”

Wang was assigned to walk the streets and take the city’s pulse. She stopped in a few corner stores. She visited the rail station—which has a train that connects to Wuhan. She tried to count how many people were not yet wearing masks. (She wrote “80 percent” in her notes.) She walked into a pharmacy and watched employees restock mask inventory within minutes. In another, she saw workers carrying out baskets full of extra personal protective equipment (PPE). A third store had sold out of masks completely.

PREVIOUSLY: How the COVID Tracking Project fills the public-health data gap

Meanwhile her colleague, Sui-Lee Wee, was speaking to sources in China and infectious disease experts in Hong Kong and Singapore. Later that day, they filed their piece, headlined China Grapples with Mystery Pneumonia-Like Illness, the first of any Times reporting on the topic. In one paragraph, the piece quotes an expert who was frustrated by the lack of access to information from Chinese scientists.

“The fact that we were trying to gauge how seriously to take this virus by how seriously people on the ground were taking it,” Wang says, “speaks to the lack of expert insight. Our best barometer at that point was how scared are normal people?”

EIGHT THOUSAND MILES AWAY, in New York City, Dr. Vincent Racaniello was intrigued when he read Wang’s article—the first he had seen about the yet-unidentified strain of disease making its way through Wuhan. Racaniello, a virologist described by some as “passionate” and by others as “rant-y,” works and teaches at Columbia University. For many years, he has displayed a poster on the wall of his office that reads: There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labor of thinking.

Since 2008, Racaniello has self-published a weekly blog and podcast called This Week in Virology (TWiV), where he hosts other virologists, biophysicists, engineers, geneticists, and —once—Dr. Anthony Fauci. TWiV has its own Facebook page and its own T-shirts. Episodes frequently run longer than two hours.

Vincent Racaniello recording a virtual classroom video for Lecturio Medical Education in 2015. Photograph courtesy Vincent Racaniello

On January 12, Racaniello recorded TWiV episode #582: “This little virus went to market.” “So we have—apparently—a new virus in China causing a pneumonia-like illness, just between this episode and last. It seems just to have hit the news,” Racaniello said, on the podcast. He then went on to read aloud from the Times piece: “A professor of infectious diseases at the University of Hong Kong, who was involved in identifying SARS coronavirus, said we can assume this virus transmissibility is not that high.”

“I don’t know why you should assume that yet.” he told his listeners. “Who knows?”

IN A DIAGNOSTIC ANGIOGRAM, doctors inject dye into patients’ blood vessels in order to make the paths of their blood flow visible. A similar procedure can, metaphorically, be performed with the narrative of the coronavirus. Tracing its outlines reveals the inner workings of a complex information ecosystem. Patterns emerge: connections, misdirection, blockages, feedback loops.

The first person to imagine any new virus—before it has a name, a shape, or a classification—is a doctor who encounters a patient with aberrant symptoms. The model of the novel coronavirus was born as early as November 2019, as a series of nebulous “maybes.” Maybe this is a new virus. Maybe it’s like SARS. Maybe it’s something we haven’t experienced before. Those “maybes” solidified with time, with additional evidence. But they also became complicated when the model moved beyond the purview of a single person.

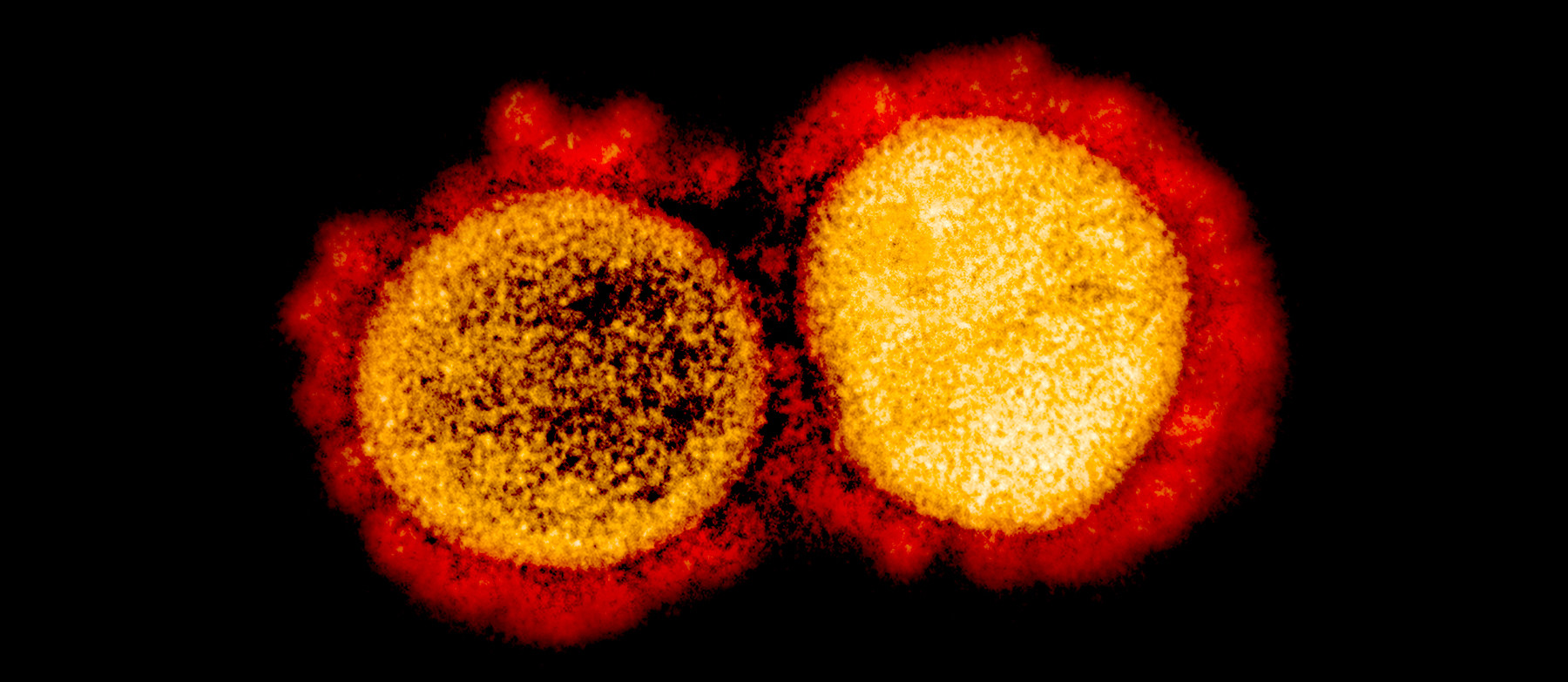

At the start of January, epidemiologists began to receive reports from public health departments in China, which included rudimentary information about the number of new infections, hospitalizations and deaths. A few virologists received a sample of the virus to photograph with electron microscopes and map genomically. “Infectious disease experts know that this is a chaotic time,” says Caitlin Rivers, a computational epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University. “And there’s no single piece of data or single piece of evidence taken to be infallible.”

While public health authorities struggle and sift through existing data and what it means, politicians hold tentative press conferences, scrambling to connect dots and, in worst cases, to conceal data points that indict them. Journalists make dozens and dozens of phone calls—to scientists, to colleagues, to anyone who might know something.

Richard Besser, president and chief executive of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, was the director of the Centers for Disease Control in 2009 during the H1N1 pandemic. Early on in the process of gathering data on that virus, he remembers talking to some of the top disease modelers in the world about the possible severity of the pandemic—using a scale ranging from one, a best-case scenario, to five, at the worst. “They said, ‘Well, based on what we can see, we think this pandemic will be a three, with confidence intervals from one to five.’ Which basically meant it could be anything from the mildest flu season to 1918,” he recalls.

Megan Cotter spent two years at the Centers for Disease Control, working as a fellow. “There is a room at headquarters that has a floor-to-ceiling array of televisions with updated stats from this country and from that country and updates from this field, epidemiologists and whatever,” Cotter says. “But a lot of lay people—like my mom—assume that there’s one Excel file with all the COVID-19 responses, that the CDC has all this information in real time, and that they’re constantly updating it. And it’s just not true.”

Newsrooms covering the pandemic were similarly chaotic. “There were all sorts of rumors and unconfirmed information flooding in every day,” Chow Chung Yan, executive editor of the South China Morning Post says of the early reporting on the virus. “The volume and the scale were way bigger than what we saw during the SARS outbreak. A large part of our job was to verify this information and separate gold from sand.”

Elizabeth Cheung, a health reporter for the Morning Post, started covering the virus the last day of December, when the government put out a notice about a cluster of unknown pneumonia cases in Wuhan. Eventually, Cheung was reporting twelve hours a day, calling hospital sources and speaking to whomever was available, checking in with public health and government sources about new reported cases. Cheung monitored Facebook groups of Chinese healthcare workers publishing anonymous complaints. At 4:30 each afternoon, Cheung watched the government briefing and opened WhatsApp, to collaborate with health reporters from other outlets to corroborate the case reporting out of each individual province in China. She checked the basic science online, and, for more complicated questions, talked to the first virologist who would pick up the phone.

“There are three kinds of people you could ask about a virus,” says Racaniello. “There’s a virologist—which is basic science—an epidemiologist—a public-health-type person—and then a clinician, who takes care of patients. They all have different views of viruses and what they do.”

Craig Spencer is in the latter category, an emergency room doctor in New York City. He began following the early reports out of China in January, doing more research of his own in February, as his uneasiness grew. He followed respected epidemiologists and public health professionals closely on Twitter. In March, as patients with symptoms began to enter American emergency rooms, Spencer and his colleagues began to cram journal articles, skim study abstracts, and, as case numbers ticked up, WhatsApp-message like mad with other medical professionals across the country. “Ten—sometimes more—messages a day, about what we’re seeing, what we’re experiencing,” Spencer says. “All of us have had to become experts in something that no one is an expert in.”

During a pandemic, knowledge is as critical as medicine. Our approach to the novel coronavirus is informed by our shared understanding, and that shared understanding is informed by our access to a host of experts, with different goals, different backgrounds, different ways of approaching the problem—experts all, but all also limited to their own scope.

“If the philosophical study of knowledge has taught us anything in the past half-century, it is that we are irredeemably dependent on each other in almost every domain of knowledge,” philosopher C. Thi Nguyen wrote in Aeon magazine in 2018. “Modern knowledge depends on trusting long chains of experts. And no single person is in the position to check up on the reliability of every member of that chain.” Perhaps the most powerful thing you can do, he told me in an interview, is to be in a position to designate who the experts are.

It’s tempting for journalists to see themselves as outside observers. They are not. Reporters gather bits of information and cobble them together—superimposing narratives, culling expert voices, using semantic sleight-of-hand to show readers where to look. The press is part of the system.

The things we know and the things we believe about this particular pathogen, driven largely by reporting, can strongly influence its global spread. Can we catch it through asymptomatic carriers? Does it live on grocery shelves? Is it safe to go to the park? Is it wise to order take-out? Journalists draw conclusions; readers make decisions.

Annie Wilkinson, an anthropologist and health systems researcher at the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex, has studied the anthropological elements of the Ebola epidemic—how sociology, culture, and human behavior influenced the spread. “Epidemics are often medicalized, in a way, but there are all sorts of social disciplines—other forms of knowledge—which are relevant to understanding what’s happening,” Wilkinson says. “There’s not always an adequate attention to conditions and voices and perspectives on the ground. People are developing their own understanding.”

A doctor can tell you whether or not you have COVID-19, based on a test or a best guess. An epidemiologist can tell you how you might create policies that incentivize people to make positive decisions for collective health, based on her previous research. A virologist can tell you what percentage of a sequenced genome demonstrates similarity to a pre-discovered coronavirus.

Journalists aren’t comfortable with the gaps in the middle. “Sometimes there is a temptation—if a scientist tells you that something isn’t knowable—to keep asking until you find someone who will give you an answer,” Caitlin Rivers adds. “But you’ve missed something important—which is that there’s actually no way to know. All of us are going to have to wait and see.”

Sometimes, the ambiguity is the answer. “What you have to do is bring the public in and say: early in a pandemic, there is enormous uncertainty. What you don’t know totally swamps what you do know,” Besser says. In the reality of an ever-shifting global crisis, journalists are only able to present a few pieces of a constantly-evolving puzzle. Reporting the pieces as if they’re the whole picture is distortion.

TWO DAYS AFTER PRESIDENT TRUMP announced a suspension of air travel from twenty-six European countries and Tom Hanks made headlines for testing positive for COVID-19, Racaniello sat in the back of a car, on his way to the CNN studios for a broadcast on the virus.

After arriving at the studio, the virologist waited in the wings, just off-stage, with CNN’s chief medical correspondent Sanjay Gupta. Racaniello remembers discussing whether or not Trump should be tested. Racaniello, to his memory, thought yes; Gupta wasn’t convinced.

Then it was time to go live. The two men stepped in front of the cameras. CNN anchor Erin Burnett asked Racaniello his first question—he had thirty seconds to answer. The quick-paced environment was jarring for a person accustomed to hour-long podcast conversations; Racaniello was featured on CNN for less than fifteen minutes. (“There was no back-and-forth,” Racaniello grumbles. “I couldn’t ask her anything.”)

“Is it really over in China, or too early to say?” Burnett asked, toward the end of their time. Racaniello gave his best answer, then the camera cut away.

ICYMI: Pushed out of Egypt for COVID-19 reporting

This story has been updated to clarify a comment from Vivian Wang.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.