Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Over the course of 16 years as co-host of WNYC’s On The Media, Brooke Gladstone has had a front-row seat to coverage of the century’s biggest stories and the changing nature of the way the public consumes and understands journalism. In the aftermath of an election result that few in the media saw coming, Gladstone asked herself a couple of questions: Why does this feel different? Why is this about more than just politics or a president?

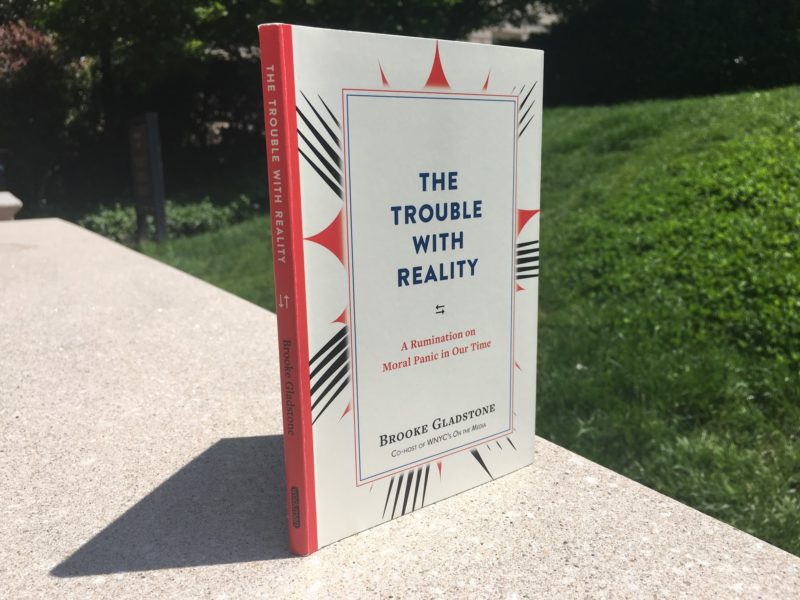

Her new book, The Trouble With Reality: A Rumination on Moral Panic in Our Time, out earlier this week, addresses those questions and is targeted at readers for whom “[Donald] Trump’s victory did not merely subvert America’s core values, it shattered their worldview.”

Drawing on the work of writers from Neil Postman to Walter Lippmann to Jonathan Swift, as well as conversations with contemporary media critics, Gladstone explores the current state of our political realities, with a focus on the multiplicity of ways people experience the world. “Part of the problem,” she writes, “stems from the fact that facts, even a lot of facts, do not constitute reality.”

The Trouble With Reality, as its title implies, is more philosophical treatise than practical guide, but it does offer some suggestions for journalists in the age of Trump. Without advocating a retreat from fact-based reporting, Gladstone argues that journalists should be open to exploring the experiences that lead people to construct their personal realities in the manner they do. Gladstone spoke with CJR about the media’s performance since November 8, the value of facts, and the very nature of truth. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Part of the problem stems from the fact that facts, even a lot of facts, do not constitute reality.

You compare the aftermath of the election to the legacy of World War I. Reading that, I thought of T.S. Eliot writing, “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” As journalists try to construct a new worldview that has been impacted by this seismic event, what fragments of the old way of doing things are worth holding onto as a foundation?

I don’t event think it’s so much about what we do as about what we believe. We believed, many of us clustered in the coasts and in the cities, that democracy was working just great the way it was, that enough people participated, and that the people who didn’t participate didn’t really matter. We believed that facts in isolation would be enough to inform people and elect leaders that would shape policy that made sense.

It turns out that all of those [beliefs] are basically wrong. Not because Trump was elected, but because people were so dissatisfied with the system that they were ready to vote for him because they hadn’t been served by the system for so long. So that foundational belief has to be reexamined and accommodated. That facts ultimately will lead to good outcomes is simply not the case. Facts in isolation will not inform a person’s reality. Facts have to be made relevant, they have to be contextualized, they have to offer a change in the narrative that people would want to strive toward, not one that simply frightens them. So a fact, on its own, is no cure-all. That doesn’t mean that reporters should pay less attention to fact-checking, but that fact-checking is simply not enough.

In the book you write, “Reality is what forms after we filter, arrange, and prioritize…facts and marinate them in our values and traditions. Reality is personal.” If we all have this personal reality, and we group ourselves in our own filter bubbles, what are the steps, incremental though they may be, that we can take toward finding some sort of collective truth?

It may be a bridge too far to reach for a common truth. Our experiences are so specific, and although we can have consensus on great swaths of our individual realities, basically we’re in a bubble that is filled with millions of smaller [individual] bubbles. The whole argument in the front of the book is that we have to filter our world to make a coherent universe.

I don’t think we can ever have a consensus reality. I don’t think we’re able to really embrace and integrate that degree of complexity. The important thing is simply to recognize that [other people’s realities] are out there, that there’s been a big smash-up on the reality highway. If you want to cobble your reality back together, you have to at least go out and explore what it collided against, if only to reconstruct a more coherent, more durable reality.

I’m not saying, “Understand people’s points of view. See how they’ve gotten to the position where their values are in such conflict with your own.” I don’t think that’s a very palatable enterprise for anybody. I’m just saying go out there and see how the people whose realities are so different from yours made those realities, from what component parts. Because, it’s going to come and smash against you again, and along the way, you might find some consensus. But I’m just saying as a matter of pure self-defense, understand, because ignorance is no refuge.

I want to ask about the larger media environment in which we’re operating. You mention Neil Postman’s contrast of Huxley and Orwell, noting that Huxley better describes our current moment (i.e., more suppressed by our own obsessions than oppressed by Thought Police). Is that a new idea that’s specific to Donald Trump, or is it the way things have been for decades?

Certainly it gets easier every day to drown out the truth in a sea of irrelevance. I’ve always believed that the access to information and the ability to filter information, to solidify our bubbles on the internet, makes us more of what we would have been anyway. Because we can tailor our information world so precisely, we can virtually eliminate the possibility of serendipity, of encounters with accidental information. And so, we can be sealed tight. There are studies that suggest that if you are a very curious person, the internet only makes you more curious, more voracious, more wide-ranging in your interests. But if you’re not a curious person, if all you really care about is, say, orchid gardening and table tennis, then that’s what your world can be, with very few incursions of information outside of those realms.

So that’s where we are now. That’s the situation we have marched to step-by-step, which I think is why Huxley was able to foresee it.

What is the danger that we face? I think it’s to our democracy.

In the book, you reach for all of these touchtones—literary, historical, and journalistic. Did that research make you feel more optimistic or more pessimistic?

Do I think the republic will survive? Is that what you mean?

Perhaps not in such stark terms, but sure.

What is the danger that we face? I think it’s to our democracy. If we’re going to talk about what we’re afraid of, and we want to break it down into something concrete, it’s that. If you’re willing to forgo breaking it down into something concrete, then it’s simply our idea about the world we know.

Speaking about democracy, one thing about studying history is that, if you realize that we have been somewhere like this before, it can make you feel a little more comfortable. But, as the expression goes, you can’t stand in the same river twice. We have this whole new technological element that enables us to be more isolated than we’ve ever been. On the other hand, we’ve had a civil war, we’ve had a complete collapse of trust after World War I, we’ve had our smug complacency challenged over and over again. We’ve faced it down.

But let’s remember how much was lost in fighting the Civil War, a war we had to fight. How much trust was lost in fighting the First World War, which maybe we didn’t have to fight. There’s a great deal that the next generation may have to reckon with before things become clear-headed again, before some kind of consensus emerges among our infinite realities. So, yeah, in the long haul, the election of Trump is just a moment in history. But in the short term, I can’t predict what it will mean; I won’t predict what it will be, because, if anything, recent history has proven that prognostication is a loser’s game.

It doesn’t really matter; they will be accused of bias anyway.

That’s the big picture. What about—based on the show you’ve had for the past 16 years—the media? Did you come away feeling optimistic about the changes that have been made, or are we still too closed off, too insular?

I would say the answer to that question is “yes.” [Laughs.] They’re still closed off and I still feel very optimistic. One thing that hasn’t stopped is the self-reflection. I don’t think the media, or much of the media, are on automatic pilot anymore. I always like to refer to the media in the plural, because you just can’t put different kinds of media in the same category. So the media that I respect, the great institutions and the new emerging institutions, do good work and they’re transparent.

It used to be that the voices from the mountains, the Walter Cronkites, were the most trustworthy. Later on it was the Jon Stewarts, who didn’t pretend to be anything other than shocked, amazed, and yet informed and honestly searching. The internet changed things. By leveling the playing field it has demanded a degree of transparency, even if the reporters have to pay for it by being accused of bias. It doesn’t really matter; they will be accused of bias anyway.

So there’s a kind of liberation in all of this, something in the book that Jack Shafer talks about. There’s an opportunity to get back to before the great consensus journalism of midcentury, which is mistitled, I think, “the golden age.” It wasn’t necessarily the best journalism. For the most part, it left out most of the world. You didn’t see people with vowels at the end of their names, people with accents, people of color. Now it’s more inclusive, and now it is more polarized. It is a great challenge and a great liberation to realize you cannot appeal to the largest group anymore. It isn’t necessary. What you can do, simply, is the very best job you can and hope that it falls on the ears of people who are searching as honestly as you are for the truth.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.