Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Ken Klippenstein is not a meme. Well, he’s not just a meme. The DC correspondent for The Nation is probably best known to the general public for starting (and winning) a Twitter fight with billionaire Elon Musk. If you don’t know him from that, chances are you’ve heard about the time he fooled then-congressman Steve King into quote-tweeting a picture of Klippenstein’s “uncle Col. Nathan Jessup” (a character portrayed by Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men) on the Fourth of July. Klippenstein promptly changed his Twitter display name to “Steve King is a white supremacist” for all of the Iowa Republican’s followers to see.

But beyond his pugnacious Twitter presence, Klippenstein, 32, has emerged as one of the most fearless reporters of the Trump era, as willing to report deeply and sympathetically on the internecine conflicts within the bureaucracies of the executive branch as he is to tweak Trump’s allies on social media. Klippenstein’s reporting on the Department of Homeland Security, his work dispelling rumors that the FBI seriously considered anitifa a terrorist threat, and sundry other scoops have made him the go-to guy for the kinds of sensitive documents most reporters would kill, or at least maim, to acquire.

And it turns out the Twitter stuff helps with sourcing, too. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

I sort of become a dissent channel for career people that I think a lot of other reporters pass up.

You moved to The Nation in January. How are you settling in?

It’s been great. They give me a long leash in terms of the time I need to pursue things, which I’m so grateful for.

Just having the time to write the stories, man! I mean, the way [newsrooms] try to squeeze quotas out of reporters—everything is going to be superficial if you have to write three or four stories a week. They seduce these kids right out of college. “Hey, you want a job for 50k?” And you say, whoa, that’s a lot of money, what do I do? “Oh, you’re on breaking news!” Well, that sounds sort of kinetic and exciting. And then after two years and a thousand stories, you’re burned out and you don’t really have any skills to bring anything else—including elsewhere in the industry.

How did you decide you wanted to be in journalism, given those pressures?

I graduated in 2010, right in the middle of the financial crisis, and the stakes seemed really high. I wanted to be a fiction writer, but then I saw everything falling apart, and it just became impossible to ignore the political situation. So I thought, Well, reporting is one way to keep writing and still address this. I didn’t have the same access to sources. I mean, you’re a reporter, you know? There are things people will tell you in person that they won’t tell you over the phone. So I had to find another approach, and when I discovered FOIA, the dowsing rod just went down. You can get your government documents for free, essentially, and they have to give them to you—in theory. Once I started getting those, a lot of the editors I had been working with didn’t really care that I didn’t have a background in media or any formal training. They really liked the primary-source documents—those don’t depend on the credibility of the reporter, because it’s just, you know, the receipts.

When did people start coming to you directly with those documents?

It really ramped up under the Trump administration. The big untold story about this administration, I think, is that there is a civil war going on in a lot of the agencies, even the agencies that you think of as being really partisan Trump people. The ICE union endorsed Trump, which is very unusual. [Even] the FBI’s trade group doesn’t get into politics like that. So you’d look at that and think “Whoa, [ICE] is made up of really partisan Trump people, you’re not gonna get anything from them!” But it turns out when you talk to the folks inside, particularly the career people—the bureaucrats, not the political appointees—they don’t like what’s happening.

One former DHS official told me he’d been tasked with chasing down people who had overstayed their visas. He said, “This is not what I signed up for. I signed up to track cartels, to monitor human trafficking.” But that doesn’t fit into the prism of this President’s ideology. [Reporting on DHS,] you will actually find a lot of people who maybe you don’t agree with politically, but have a lot of reservations about the way things are being pursued.

So I sort of become a dissent channel for career people that I think a lot of other reporters pass up.

You went to [Christian college] Wheaton, right?

Yeah.

I assume that means that you’re from a fairly conservative background.

Oh yeah. I couldn’t tell you how many people in the intelligence community I meet—particularly older guys, who are very Christian—and, when they see that, they’re like, Oh, a young Wheaton man! I’m happy to talk to you. I have a very weird Christian background. My parents are Christian, but my dad is Mennonite. Do you know what Mennonites are?

Sure. Where I grew up I remember we had Mennonites selling honey at the gun shows.

They’re a very heterodox group because, I guess, they have a lot of conservative views, but then they’re sort of like the Quakers in terms of being really into pacifism and left-wing foreign policy. So I never really slotted in with the kind of conservative Christianity you might think of, although they were intensely religious, and that helps a lot with being able to interact with certain sets of people. I still have a lot of affection for that religious tradition. It helped me think about things.

How did you learn to write a FOIA request?

Oh, the same way I learned everything—by pestering the people who were doing it. They were mostly very kind. I bugged the people at MuckRock a lot—there’s a whole culture of FOIA warriors, and they’re kind of like my sources. A lot of them are libertarian conservative types. I don’t know why that is. The left doesn’t do that stuff as much. And then a lot of it was just fucking around, which is how I’d characterize my entire approach to everything. Eventually something works, and then you just keep doing that.

Ken Klippenstein, via @_anunnery/Twitter

It’s really notable that you’ve managed to succeed in political journalism, where it often feels like everyone knows everyone else from school.

When I was younger, I was worried about that. If everybody knows each other, how am I gonna get in here? I didn’t go to one of these fancy schools! And then as I got older, I realized that it’s actually sort of a crutch: if you do that, you get to rely on these types that end up becoming the political appointees I was describing before. The dirty secret of some of the big legacy papers is that they’re getting a lot of their stuff from the White House. I’m not saying not to do that—it’s important to learn things from wherever you can—but if you’re only going to the politicals, you’re not going to hear what the rank and file have to say. And they’re often at loggerheads with each other.

So what do you feel is under-reported at the moment? What should we be reading more of on your beat?

I would love to read more coverage on the case for reform of DHS, not from the left, but from DHS rank and file. So many people I talked to there are very conservative but would love to dismantle the agency—not by vaporizing all of its components, but by returning those components to the agencies that they used to be under. Almost all the agencies within DHS, other than intelligence and analysis, already existed under other auspices [before DHS was formed in 2002].

Like when there was an Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Exactly. And the Secret Service used to be under the Treasury, and so forth. A lot of these guys want to go back to that. Of course, I think there should be a moral case for not, you know, splitting up families at the border. That’s clear! But there are other debates and other arguments, in addition to that, that could appeal to different types of people. House Democrats are suddenly looking at this seriously. So I think that it’s a really important time to do that kind of thing.

The Nation’s audience is very lefty and a lot of what you’re writing would potentially be of interest to very conservative DC audiences. Are you looking to broaden horizons there?

That is absolutely my aspiration. In my opinion, a lot of the national security reporting tends to be pretty… if not reactionary, then center. And there’s a lot of appetite for something different. I do get screamed at by lefties sometimes—Why are you friends with ICE people, and things like that—but if they want to dismantle the agency, if that’s what they’re interested in learning from this reporting, they should understand the parts and pieces and how they go together.

Do you remember when the Mueller report came out and everyone was talking about SIGINT [signals intelligence] and all that?

Yes! Everyone started writing proper names in all caps.

It’s so annoying! But it also marginalizes ordinary people who don’t have time to learn all the weird lingo.

The point seems to be make people feel like they’re too stupid to understand it so they have to follow us on Twitter or buy our books.

Yeah. I mean, it is complex, but you don’t have to understand it on a technical level, as though you were going to go and work for the FBI. You just need to understand the big picture. Readers want to understand whether something is advancing the public interest or not. That’s a much easier picture to paint.

So, have you heard from Steve King lately?

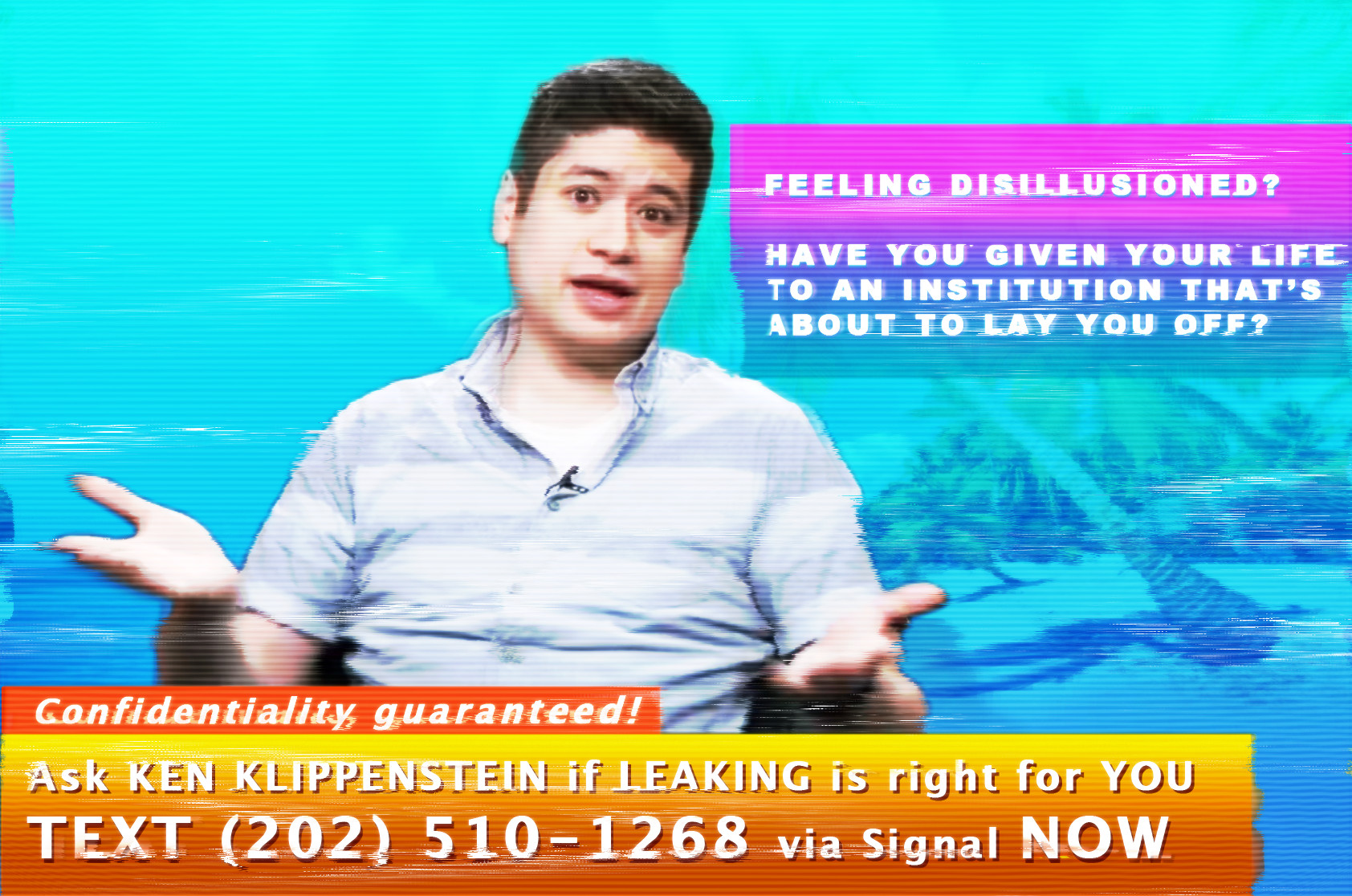

[Laughs.] No, I haven’t heard from him. But you would be amazed how many sources I’ve gotten who are like, “Hey, aren’t you the guy from Steve King?” I’d much rather be known as the guy who has some public interest story that advanced an important discussion, but unfortunately, it’s “Are you the Steve King guy?” But then they’re like, “Oh, this is so great! You know, I’m in such-and-such a federal agency, can you help me with a story?” Even people from the intelligence community. I’ll get spooks who reach out! It’s so weird.

When I came into this, I thought, “Oh, I’m going to break stories, and people will see me as credible on the issues, and then stakeholders in that little field will reach out.” Nope! I mean, that has happened, but there have been many more responses to these insane memes, like Elon Musk screaming at me and calling me a douche. Far more people reach out and leak stuff to me over that than over stuff I’ve written. But that’s how it goes, I guess.

There’s a big generational divide over whether or not to mind your manners when powerful people are behaving badly, and it sounds like not doing so has paid off for you.

Well, I was never properly socialized at a journalism school, so I wouldn’t even know how to follow the decorum even if I wanted to. Sometimes I end up violating little norms that I don’t even understand. People tell me that, and I’m just like, “Dude, you’re telling me that if I clean up my act, people will talk to me instead of a seventh-generation Yale grad?” My view is always that you’ll never be able to be more deferent and polite than those guys, so why even fucking try?

RECENTLY: Television is making more documentaries than ever—but skipping the journalism

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.