Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

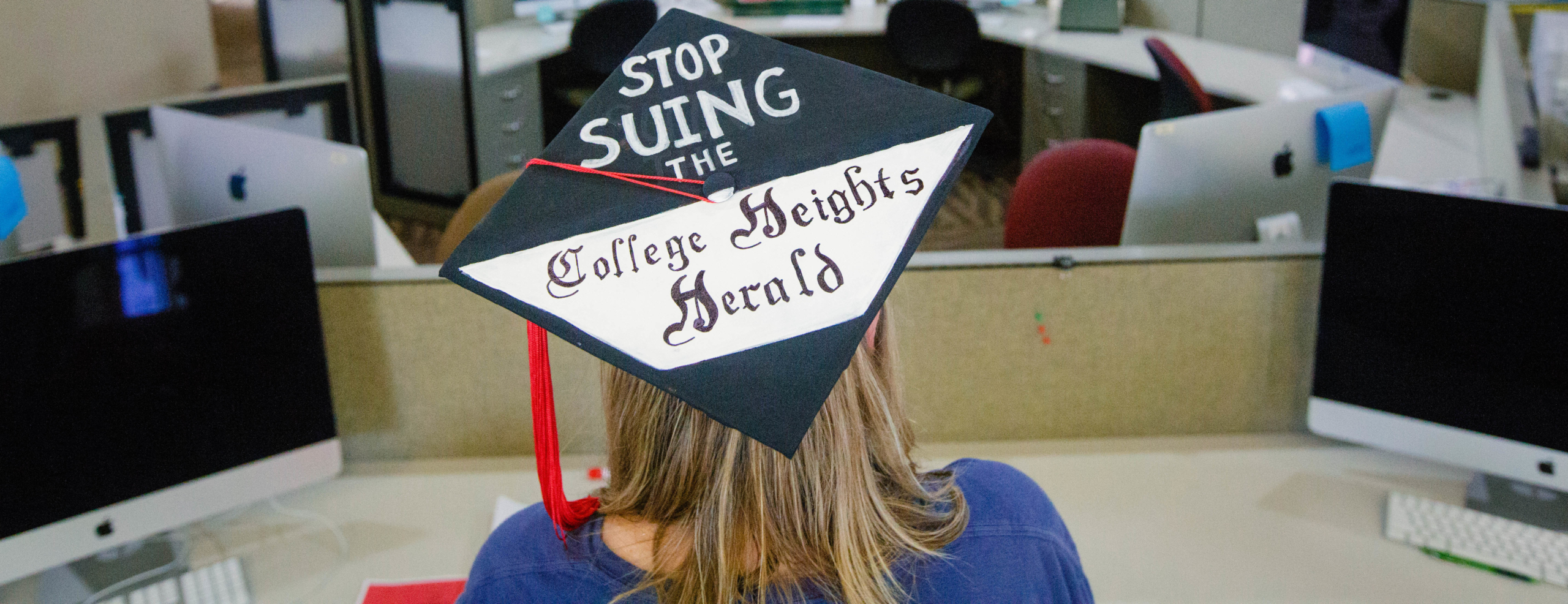

The Kentucky Court of Appeals ruled on Friday that the University of Kentucky failed to comply with the state’s open records act when it refused to give UK’s student newspaper, the Kentucky Kernel, information about the investigation of a professor accused of sexual assault. The May 17 ruling is the latest twist in a legal fight that has put student journalists at UK and Western Kentucky University in the uncomfortable position of trying to cover their universities while simultaneously being sued by them.

Since 2016, UK and WKU have resisted requests for records of Title IX investigations against employees accused of sexual harassment or assault. Because of a unique feature of Kentucky law, the only way the universities could block disclosure was to sue the Kernel and the College Heights Herald, WKU’s newspaper. (A suit brought by WKU against both the Herald and the Kernel is pending in a trial court in Bowling Green.)

“This suit between the Kernel and UK has literally been going on for my entire college career,” Bailey Vandiver, the Kernel’s outgoing editor in chief, says. “So I’ve never known what it would be like to work at a newspaper that’s not being sued by the university.”

The universities insist that they are trying to protect the privacy of students who have been victimized, and argue that the Title IX files are educational records protected from disclosure by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). However, six other Kentucky universities also covered by FERPA have complied with similar document requests from the Kernel and Herald, and attorneys representing the newspapers believe the real motive is to preserve the public image of both universities by preventing scrutiny of their handling of Title IX complaints.

“It’s all about the university trying to save face,” Tom Miller, a Lexington attorney who represents the Kernel, says. “It just pisses me off. And then they turn around and sue their own students.”

Among the lawyers representing the Herald is Jon Fleischaker, who wrote the state’s open records act as counsel for the Kentucky Press Association in the 1970s. He and his wife, Kim Greene, also underwrite a First Amendment scholars program at WKU, and he has raised objections to the lawsuit with WKU’s current and past presidents, to no avail. (Disclosure: I oversaw the First Amendment scholars program in the fall semester of 2018.)

“There are people in the administration who are bad-mouthing their own students,” Fleischaker says. “That really disturbs me.”

An investigation by WKU journalist Nicole Ares, based on Title IX investigative documents she managed to obtain from five Kentucky public universities, buttresses the case for why disclosure is in the public interest. Ares found that only half of the 62 employees found to be in violation of sexual misconduct policies between 2011 and 2016 were fired, and at least eight had gone on to other schools, which in some cases were unaware of the previous allegations. Ares’s reports didn’t include information on six WKU employees tagged as violators because the university blocked access to those documents.

Ares’s stories about the sexual misconduct complaints have won a slew of prestigious national awards, from the Associated College Press and the College Media Association, among others. While universities are usually quick to publicize student honors, Chuck Clark, director of student publications at WKU, says, “there hasn’t been any university acknowledgement of those awards.”

The events leading up to the disputes between the universities and their newspapers began in the spring of 2016 when a source approached Marjorie Kirk, then news editor of the Kernel, about an investigation of UK entomology professor James Harwood, who was accused of sexually assaulting and harassing graduate students he supervised. Kirk says she was told Harwood had been allowed to resign rather than face disciplinary action, and the university had agreed not to disclose any information about the allegations to subsequent employers.

The Kernel filed an open records request for the Title IX investigative report, which UK denied. Even with identifying information redacted, the university argued that releasing the records would reveal student identities.

“We believe strongly that the victim survivors have that right to privacy,” Jay Blanton, UK’s chief communications officer, says. “That’s been the principle that we’ve adhered to throughout this case.”

UK continued to resist disclosure even after a source gave most of the documents to Kirk, with student information redacted; Blanton said the university still had a “moral responsibility” to try to protect the students’ identities.

Meanwhile, at the Herald, Ares had been following the Kernel’s coverage and decided to file an open records request for Title IX investigative files from seven Kentucky public universities. The Kernel had made made a similar request.

Of the seven universities, five complied, including UK. WKU and Kentucky State University declined to comply, citing FERPA in their refusals. When the Kernel and Herald appealed to Attorney General Andy Beshear, who arbitrates open records disputes, the universities also refused to turn over the documents to his office for review, at which point he sided with the newspapers and ordered that the documents be released. Because the open records act precludes lawsuits against the attorney general, the only avenue left for the universities to prevent disclosure was to sue the newspapers.

KSU eventually turned over redacted documents after losing at the trial court level; WKU’s suit against the Herald and Kernel to block release is yet to be resolved.

We think it’s a pretty definitive statement that the university can’t hide behind student privacy to shield information about employees who engage in wrongdoing.

Though Beshear wasn’t a party to the universities’ lawsuits, his office took the unprecedented step of intervening in the cases on the side of the newspapers.

“The open records act is not meant to be a ‘trust me’ law,” Travis Mayo, executive director of the attorney general’s Office of Civil and Environmental Law, says. Allowing state agencies to decide for themselves whether records are exempt, without an independent determination by the attorney general, “would defeat the purpose of the act,” he adds.

The Court of Appeals agreed with UK that students in the Harwood case have privacy rights that UK must protect and that records protected by FERPA aren’t subject to the open records act. But it rejected the university’s blanket assertion that FERPA protects all of the records and sent the case back to the trial court, with instructions that the university provide a legal justification for any documents it wants to withhold and redact any information that identifies students. Blanton says UK would review the court’s ruling before deciding on its “next steps.”

Michael Abate, a Louisville lawyer whose firm is representing the Herald, says the Court of Appeals ruling against UK should help the newspaper prevail in its suit with WKU.

“We think it’s a pretty definitive statement that the university can’t hide behind student privacy to shield information about employees who engage in wrongdoing,” he says.

In an email, Bob Skipper, director of media relations at WKU, said the university does not comment on pending litigation, and that “our reasoning for taking this course of action is clear in our court statements.”

To date, UK and WKU have spent more than $134,000 on legal fees pursuing the lawsuits. The newspapers have financed their defense by cobbling together funds from alumni donations, the Kentucky Press Association’s legal defense fund, the Society of Professional Journalists’ state and national organizations, and through the generosity of lawyers dismayed by the universities’ litigiousness.

“We have donated a fair amount of labor to the cause, and we’re happy to do it,” says Abate, who adds that he wanted to defend “students asking hard questions of people in power.”

The KPA’s executive director, David Thompson, says the association is committed to seeing the cases through because of the precedent that would be set if the universities prevail. “We know [the newspapers] are not going to have the resources to keep going,” he says. “We want them to keep going.”

If the newspapers prevail, they can collect attorneys’ fees from the universities if non-compliance is deemed “willful,” in which case the entire cost of these legal cases could come out of university funds.

In the meantime, student journalists at UK and WKU continue to navigate covering news stories involving people whom their newspapers are facing in court. “[We] try to help make the students realize that, yes, the university is suing them, but that can’t change the tone or tenor of how you cover the university,” Clark says.

Vandiver believes the lawsuits haven’t changed how she and her colleagues at the Kernel cover the university. “We would be as skeptical of the university as would have been if we hadn’t been sued,” she says.

ICYMI: Teacher discusses student sex worker profile

Correction: This story previously misidentified a former Kentucky Kernel editor. She is Marjorie Kirk, not Marjorie Kurtz.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.