Last February, Celeste Headlee was at home, in Atlanta, when she received a call from John Biewen, the head of the audio program at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. Like Headlee, Biewen is a veteran of public radio—he spent nearly a decade and a half as a reporter, working for NPR News and stations in Minnesota and the Rocky Mountain West. But he’d since transitioned into podcasting; Seeing White, his 14-part series on the history of systemic racism in the United States, had recently been nominated for a Peabody Award.

Biewen was getting ready to produce a follow-up that would use the same basic structure as Seeing White: many of the interviewees would be scholars and scientists; other segments would look at present-day politics. He was hoping that Headlee would sign on as cohost. “I remember asking, ‘Well, what’s the topic?’ ” Headlee recalls. “John goes, ‘Gender. Masculinity. Men.’ And I thought to myself, ‘Oh boy.’ I was concerned, to be honest, because I figured I knew why he’d called me.”

A few months earlier, Headlee, a former cohost of The Takeaway, a news program on WNYC, had been one of several staffers to publicly accuse John Hockenberry, another cohost, of sexual harassment, misconduct, and bullying. In doing so, she’d violated a nondisclosure clause she’d signed with WNYC, and the potential legal peril she’d put herself in, along with the emotionally draining interviews she found herself giving when Hockenberry was ousted, had taken a toll. (She left a subsequent gig, as host of a Georgia Public Broadcasting show called On Second Thought, citing exhaustion.) “I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life talking about what had happened,” Headlee says.

At the time, conversations about who gets to tell whose story, in what venue—and above all, who is believed when they speak—were everywhere. The #MeToo movement was ascendant; Moira Donegan had just published a long essay in New York Magazine defending her decision to create a spreadsheet chronicling alleged harassment and abuse by men in the publishing world. Some of those men, including Hockenberry, would go on to receive platforms to tell their stories in prominent literary outlets. As never before, editors, successfully or not, began reckoning with how they had overlooked—or actively ignored—voices that needed to be heard. That process, which is still ongoing, could be uncomfortable and in ways frustrating, even when productive.

Headlee wasn’t sure she wanted to be the midwife to Biewen’s self-awareness. On the call, he tried to put her at ease. Yes, he knew how absurd his ask sounded: he was a white, middle-aged, middle-class cisgender dude recruiting a woman of color to help him make a show about centuries of male oppression. But in a sense, that was precisely the point. He wanted to create a podcast that would confront a subject that, in another era, a man might never have waded into at all. “He told me that all the #MeToo revelations had been hitting him really hard,” Headlee remembers. “He said there were obviously things he hadn’t seen, and he wanted to turn that into an opportunity, a chance to really tell the full story of how we got here.”

Headlee thanked him for the offer and told him she would think about it. In the following days, something about their conversation stuck with her. “John had said he wanted to show that sexism isn’t a female problem”—in other words, that it wasn’t a problem that women should be responsible for solving on their own. “I had full support for that,” Headlee recalls. She began to imagine: What if every man took responsibility for the failings of the patriarchy?

In the spring of 2018, Biewen flew from North Carolina to Boston to meet with Headlee and John Barth, the chief content officer at PRX, a media group that was interested in partnering with the Center for Documentary Studies on the project. It was a “trial run,” Headlee says, and the potential was evident: “We hit it off immediately; we had chemistry.” They talked for hours about directions the show might take. Biewen already had an all-caps title, MEN, and a potential opening segment, about a childhood incident in which he’d been smacked around by an older sibling and, in a fit of prepubescent machismo, had taken out his rage on his little brother, Todd. (In one of the most affecting parts of the finished episode, “Dick Move,” Biewen calls Todd and, for the first time, apologizes—but his brother has forgotten the incident. The trauma is all John’s.)

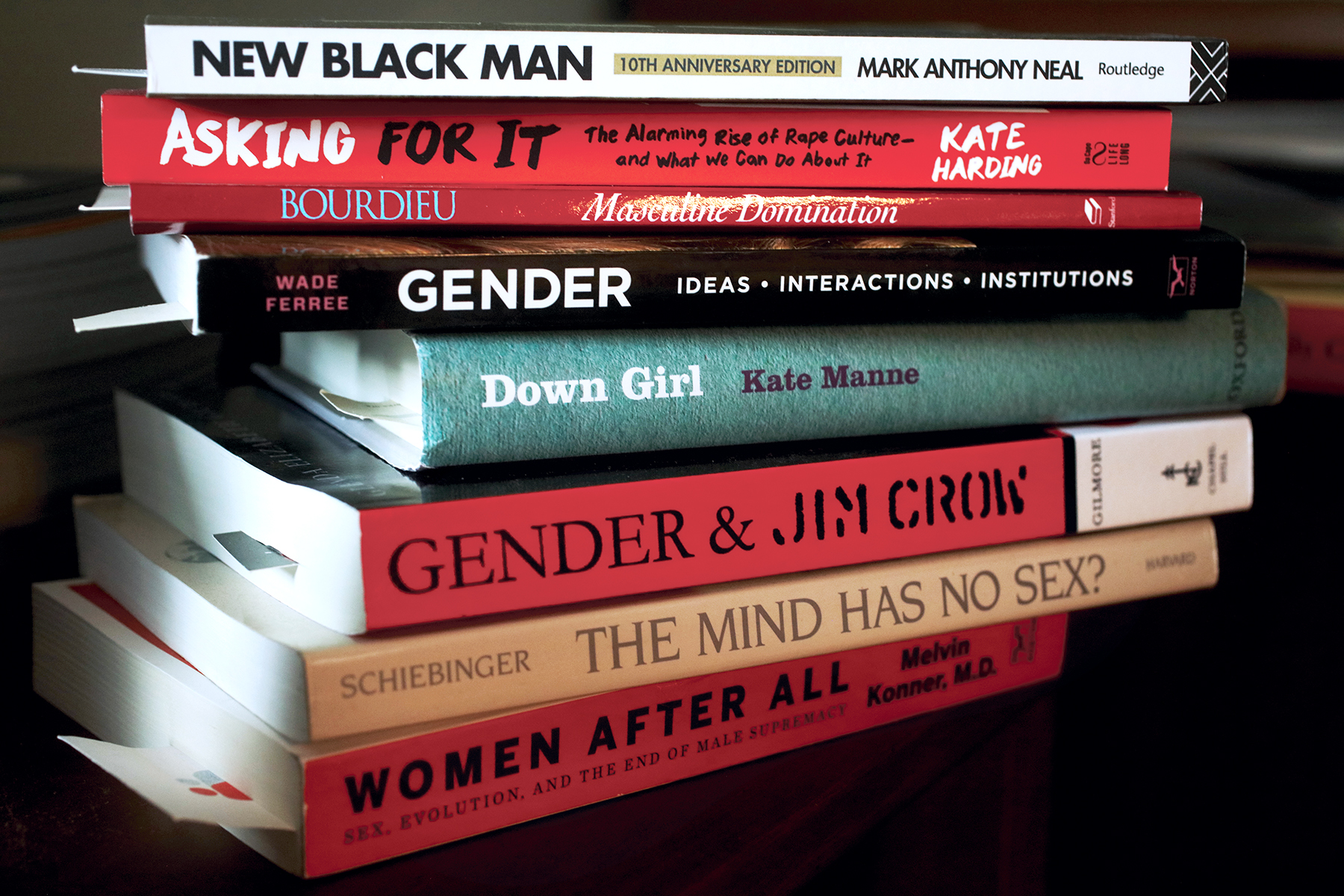

Headlee had ideas of her own. She suggested, for example, that Biewen reach out to Melvin Konner, an anthropologist and the author of Women After All: Sex, Evolution, and the End of Male Supremacy (2015). Konner had spent two years conducting fieldwork among hunter-gatherer tribes in Botswana, where women have long played a central role in decision-making. Headlee liked the idea of puncturing the myth that historically and across cultures, gender roles have always been fixed.

In June, they began recording the first episodes of MEN. Headlee laid out the mission statement: “A season-long dive into patriarchy, sexism, misogyny—”

“And other words with lots of syllables,” Biewen chimed in. “Masculinity and male supremacy, past and present.”

Headlee knew how ambitious their plan was. “To try to take a big, complicated topic like this, to try to balance the journalism and the introspection, and to try to get people to engage with the material in an intimate way, to really swim in it—it’s something that other programs have tried and failed to get right,” she says, between edits on the final episode of MEN. “It’s something that’s easy to mess up. John and I were aware of that at the start.” She adds, “We’re definitely still aware of it now.”

John Biewen, who is 57, is slender and tall, with once-brown hair that has gone gray with age. One of five kids, he grew up in Mankato, Minnesota, an overwhelmingly white town on a deep bend in the Minnesota River. His father was a high school teacher and basketball coach; his mother was a guidance counselor. He did not set out to be a journalist. He tells me that “the moment I knew I wanted to be in radio came after I was in radio.”

And even then, he waffled. In 1983, shortly after Biewen’s graduation from Gustavus Adolphus College, a liberal arts school near Mankato, his favorite professor suggested he try working in public radio. Biewen spent the summer interning at a local station; when that gig ended, he was hired as news director at KCCM, a small station in the town of Moorhead. “I still didn’t think it was my career,” Biewen says—a stretch teaching in Japan and an abortive stint in a PhD program in philosophy followed. But by 1987, he was back in Minnesota full-time, working as a reporter for the Minnesota Public Radio flagship in

St. Paul.

He remained in public radio for 19 years. Biewen profiled poor farmworkers in Texas and Minnesota families forced to scrape by on food stamps; he traveled to the South Side of Chicago, to Ojibwe and Navajo reservations, and to Japan, to interview survivors of the Hiroshima bombing.

Photo by Travis Dove

He also worked on stories that delved into the same tortured history he’d later explore in Seeing White: in 1994, he made an hour-long radio documentary called Oh Freedom over Me, which he has come to regard as the most important project of his early career. Set in the “Freedom Summer” of 1964, the piece tracked the work of young volunteers conducting voter outreach in African-American communities in Mississippi, and the violent reaction of police and locals, among them members of the Ku Klux Klan. As journalism, Oh Freedom over Me is masterful: tragic and elegiac, but—with its use of historical footage and interviews from participants—visceral, too.

And yet compared to Seeing White, Oh Freedom is traditional in its approach; if not quite dispassionate, it nevertheless maintains something of an editorial distance. Originally, Julian Bond, a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, narrated Biewen’s script; in 2001, when Oh Freedom over Me was updated and re-aired, Biewen did the narration himself. “The detached journalist, above or outside of it all, just narrating the facts,” he says of the experience.

Recently, I emailed Biewen to ask if he had ever given any thought to adding his own perspective to the project. He wrote back nearly 1,000 words. “I certainly felt some unease, some sense that this was not—let’s put it this way—the optimal way to do things,” he said. “But I didn’t yet have the clear framework or language for expressing how else to do things and, just as importantly, this is how things were done in the world in which I was working and it was considered OK. I remember thinking, about the Oh Freedom project in particular: It would be a lot better if, say, a Black Southerner were reporting and telling this story,” he went on. “Or a white Southerner, for that matter. But, what are you gonna do?”

Biewen credits Ira Glass of This American Life and Sarah Koenig of Serial with helping demonstrate that there is another way to create potent radio journalism—one that is scrupulous and precise while allowing the perspective of the writer to come through. “You have permission to put yourself and your reporting and thinking process into the story,” Biewen says of what he learned from early podcasts. “It knocks down the walls between the storyteller and the story, and between the storyteller and the listener—walls that everybody knows are bogus anyway.”

Still, it wasn’t until 2016 that Biewen committed to a season-long podcast whose focus, in a sense, would be perspective itself. At that point, he’d been the audio director at the Center for Documentary Studies for eight years, during which time he’d overseen the launch of the organization’s first podcast, Scene on Radio. The first season, in Biewen’s estimation, was a “hodgepodge” affair, consisting of his old clips and sometimes the work of his students. Listenership was frustratingly low: 5,000 downloads a month.

“John had said he wanted to show that sexism isn’t a female problem”—one that women should be responsible for solving on their own.

Then, one afternoon, he got an email from his boss: a group called the Racial Equity Institute was holding a workshop not far from the Duke campus, and all CDS employees were encouraged to attend. Biewen signed up. Not reluctantly, precisely, but with a feeling that he wasn’t the target audience. He figured he was far from it, being both the product of a progressive upbringing and a self-described “good anti-racist from way back.” As he recalls, “I thought, ‘Yeah, I’ll go do this anti-racism training. But I kinda got this, right?’ ”

In the event, the workshop, led over two days by a North Carolina educator named Deena Hayes-Greene, turned out to be structured differently from how Biewen had imagined. The focus wasn’t on how to avoid putting your foot in your mouth when talking about race—it wasn’t about phrases never to use, or conversations one should never have in the workplace. Instead, it was a lengthy exploration of how deeply racism is encoded in the DNA of America; it was about how difficult—impossible, really—it is to separate the formation and development of the United States from the pervasive, comprehensive, enduring subjugation of people of color. Working forward from the earliest days of the colonization of North America, Hayes-Greene covered the endless ways that whites have used racism to get ahead, from land drives on Native American territory to slavery and its aftermath to insidious modern ploys such as redlining—a government-led effort to funnel investments into white neighborhoods, while allowing predominantly Black areas to fall into decline.

By the time the workshop concluded, Biewen felt that Hayes-Greene, in her clear-eyed account of systemic racism, had provided him, a white guy, with an opportunity. “I thought, ‘OK, there’s clearly a huge gap between the way that the average American—including the average sort of liberal white American—sees our country, and the real story,’ ” Biewen says. “And as a journalist, that’s a story, right? You’ve got something to work with there with a gap like that. Basically, I came out of the REI workshop thinking, ‘What if I was to do a whole series on this? On whiteness.’ ”

The field of “Whiteness Studies,” as it is often termed in academic circles, has existed for decades. Writers ranging from W.E.B. Du Bois to Theodore W. Allen, the author of The Origin of Racial Slavery: The Invention of the White Race (1976), have looked at the way whiteness has evolved as an ideology and a construct. In doing so, they have called into question the supposed objectivity of the work of generations of straight, white, male scholars—and helped redefine how the story of our country is told.

Journalism has been slow to catch on. The vast majority of newsrooms around the country are, and have long been, extremely white. Perhaps it’s no surprise that white reporters have historically failed to adequately cover minority communities and concerns. Dominant narratives in the press assume a white, male perspective—even on matters of civil rights. In stories, the race of the subjects is often mentioned, but the race of the writer is rarely acknowledged.

This was the case with some of Biewen’s journalism, including his piece on the Freedom Summer. “I liked to think of myself as a person who had always been sympathetic to the cause of people of color,” he explains. But, “There was also a sense in which that was their cause and I was over here cheering, rooting them on. And that’s crazy, when you think about it. You have to personally deal with the extent you’ve benefited from it. You can’t just sit back and observe.”

After leaving the REI seminar, he decided his new project would do far more than merely observe—it would be a process, a journey, one that the listener would take with him. As would later be the case with Celeste Headlee and MEN, he was not oblivious to the optics. He needed a copilot, someone to help him process what he would learn. He thought of Chenjerai Kumanyika, a young journalist and assistant professor at Clemson he’d met at CDS events. “As a Black person, when you’re asked to talk about race in popular media, you’re dealing with a situation where the gatekeepers are white, the audience is largely white, and there’s a certain expectation they have,” Kumanyika tells me. In his experience, when talking about race, white people tend to want absolution or praise. He adds, “The dominant line of inquiry is attitudes.” But he’d rather talk about the systems that allow racism to flourish, “about what it’s like to live as a member of a group that is marginalized and oppressed.”

He decided his new project would do far more than merely observe—it would be a process, a journey, one that the listener would take with him.

He accepted Biewen’s assurances about Seeing White—that it would address the gamut of institutionalized racism in the US, not just “attitudes”—and by early 2017, Biewen and Kumanyika were talking regularly by phone, with Biewen often recording their exchanges. Episodes of Seeing White include versions of those conversations, which have an electric energy. Biewen acknowledges that he was never able to get a full picture in his previous work on race (“If I think about how I built those stories,” he says, “I’ve often treated whiteness like the proverbial elephant in the room”); at other junctures, he acts as a stand-in for a liberal white listener, confessing that he has “bristled” when people make sweeping assessments of the racism of American whites (he is, after all, one of the “good ones”).

Kumanyika acts as prod and goad, encouraging Biewen to go further—to question the way race seeps into even the most quotidian aspects of life. At those moments, Kumanyika is transforming Biewen from host and creator to subject. In one episode, Kumanyika asks Biewen, “When you graduated from college, right? Did you feel like that was a victory for white people?”

“No, I did not,” Biewen replies with a laugh. “That thought never crossed my mind.”

“But, like, when I graduated from college, I felt like it was a victory for Black people,” Kumanyika continues. “And when I got my PhD, I felt that and was told that.”

Photo by Travis Dove

Had the entire podcast consisted of exchanges like this one—lighthearted in tone, serious in subject matter—Seeing White might already have been successful. What makes it so effective, however, is the mating of confessional segments with historical passages. Biewen delivers incisive interviews with Nell Irvin Painter, a historian, and with Ibram X. Kendi, a professor and the author of Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (2016), about the European origins of contemporary American racism. (The colonists, Kendi says, not only brought over cargo to the New World, “they brought over these racist ideas in their minds.”) He talks to Janet Monge, a curator at the Penn Museum, in Philadelphia, about how phrenology—the measuring of skulls—was used to reinforce the idea that white Europeans were smarter than African-Americans; he features Tehama Lopez Bunyasi, a political science professor at George Mason University, on the bizarre and tragic cases of two foreign nationals, Bhagat Singh Thind and Takao Ozawa, who in the 1920s were compelled by federal courts to “prove” they were white as a condition of American citizenship.

Biewen also investigates his own unthinking respect for figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson—a so-called Great American Man possessed, it turns out, of an incredible amount of outdated, outwardly racist ideology. Having uncritical notions of historical narratives is “one of the main features, I think, of whiteness and of being an American, and of this story we tell ourselves,” Biewen says. “It requires a lot of willful forgetting, and we’re very good at it. We have lots of practice.”

Seeing White quickly generated buzz. Downloads of the series soon climbed into the six digits per episode; five-star reviews piled up on iTunes (more than 3,000 at last count), as did praise on social media. (The overwhelming positivity was striking; my efforts to find negative responses turned up nothing of substance.) “A lot of the feedback boiled down to ‘Why the hell aren’t we taught this in school?’ ” Kumanyika says.

Many of the listeners were progressive whites, like Biewen. But “I know from talking to folks that it had a lot of appeal to people of color,” Kumanyika tells me. “And it was cool watching the different ways it was used. We had church groups telling us they were using it as a teaching tool—podcast clubs and community groups, too.”

One of those groups was a San Francisco affiliate of Showing Up for Racial Justice, or SURJ, an advocacy organization. “I think the way the show approached racism by turning the lens on white people—that’s not something that’s normally done,” says Adee Horn, a high school teacher who is a member of SURJ. She invited Kumanyika and Biewen to Skype into a SURJ meeting, and has since encouraged her students to listen to Seeing White. “We’re basically taught not to think about the tarnished parts of our national history,” she adds. “But Seeing White does. I think it helps us face some of that directly.”

Last year, another educator, a North Carolinian named Michael Parker West, recommended Seeing White to a colleague in the Wake County Office of Equity Affairs, which runs training sessions for teachers in and around Raleigh. “Mike and I met up again sometime later, and we gushed,” Christina Spears, the colleague, tells me. Together, they built a nine-week class for Wake County teachers based on Seeing White, complete with discussion prompts, additional readings, and an online forum. Twenty-five teachers were selected for a pilot program. “I saw educators, people from all walks of life, talk candidly about their understandings of history, race, and whiteness; we shared our own racial identities and stories,” Spears recalls. She’s now in the process of planning another course.

“I think this idea has faded away that we were going to be completely objective and that we are not going to place ourselves in the story—that already feels a little outdated.”

As for MEN, the follow-up, downloads have kept pace with those of Seeing White, and the continued fallout from a number of #MeToo scandals has meant that the material has stayed relevant. “I truly believe that listeners have realized that John and I, in every episode, we’re telling the truth,” Headlee says. “And people have responded to that.”

In a sense, Biewen’s work with Seeing White and MEN may represent a larger change in the industry: an acknowledgment that it’s sometimes okay, and even preferable, for journalists to be candid about the perspective (or lack thereof) they bring to a piece. “I think this idea has faded away that we were going to be completely objective and that we are not going to place ourselves in the story—that already feels a little outdated,” Biewen tells me when I meet him in his office at Duke.

It’s a brisk winter day, bright and windy, and the afternoon sun falls across Biewen’s desk, which is cluttered with books and papers. Biewen looks happy but a little worn—reporting and taping MEN is in essence a full-time job, and he still has to juggle it with his duties as a CDS instructor. But he is already mulling an idea for his next project. Without yet knowing the exact framing, he envisions a season devoted to exploring American democracy—“our peculiar, deeply flawed version of it”—and how the government has fallen into crisis.

I wonder aloud if Biewen feels that he’s been altered by his recent work—not changed in a career sense, but transformed personally. His eyes wander over the dual computer screens in front of him, one of which is open to an edit of an episode of MEN. Finally, he says, “I guess the word I keep coming back to is clarity. Like, I almost want to blush when I see the things people write in reviews. Stuff like ‘life changing.’ But I think to some people that’s what it does feel like, because we really are putting forward something that’s at odds with what they thought they knew.”

He pauses. “And there’s a little of that for me, too,” he goes on. “Clarity. Like, ‘Oh, now I see.’ ”

Matthew Shaer is a writer-at-large for The New York Times Magazine and a correspondent for Smithsonian Magazine. He lives in Atlanta with his family.