Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

“The best minds in media should be giving sustained attention to how to tell [the climate crisis story] in a way that creates change,” wrote Washington Post columnist Margaret Sullivan in October. The question is, after two striking reports on the compounding threats of climate change in just two months, is this call to action being echoed across the media landscape? To find out, I analyzed a dataset of more than 650 climate-related articles produced in the past two months.

Whether you’re a climate reporter or just a concerned citizen, the last few months were a tumultuous time for climate news. On October 8, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a bombshell report on the potential catastrophes wrought by reaching 1.5℃ above average global temperatures; one month later, on November 23, the White House produced its National Climate Assessment, correlating many of the same dystopian predictions: mass migration, diseases, more wildfires and hurricanes, extinction of the world’s coral reefs, and resource-driven wars. We have a decade to stop this from happening. And yet most news organizations have historically fallen into the trap of relegating the updates on major scientific breakthroughs or environmental warnings to… well, turn page one over.

After analyzing both the size and scope of climate coverage during the past two months, here’s what I found: climate change coverage has predictable peaks and valleys, but the volume and consistency of deep dives indicates that explainer journalists are maintaining the climate conversation when hard news begins to teeter. Hard news coverage appears to have increased in number and attention span by the second report’s release.

A note on methodology: I used data analysis software, Media Cloud, and created the keyword, “climate,” to generate a cache of search results dating from the IPCC report’s release date on October 8 through December 1. After filtering out non-environmental pieces, I wound up with roughly 650 articles, which I later filed into a Google spreadsheet and coding program, R. Among those news outlets represented were a wide range of breakneck news giants like CNN and Fox, The New York Times and The Washington Post, among more digital-native publications like Vox. And yes, Breitbart and several other extreme commentary websites were included, as well too, for impartiality’s sake.

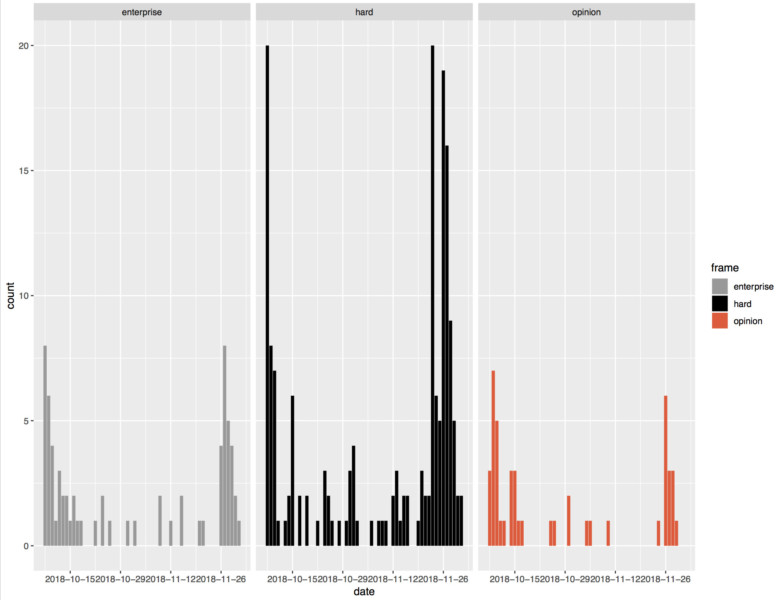

Using designations for hard or breaking news, enterprise or feature writing, and opinion, I cataloged the framing of each piece. How we frame the story could change who sees it. For instance, a newsletter reader that gets the Post through email would need updates on the IPCC report to be filed under page one every day. Of course, this can’t always happen.

In my example, “hard” coverage defined coverage on the inner-workings of the IPCC or White House reports and their release, while pieces that took a deep dive on a particular subject were labeled as “enterprise.” For example, I considered a story about 47,000 ticks found on a single moose due to climate change to be an enterprise story. Finally, opinion pieces generally tracked interpretations of the report’s findings, from The Guardian’s describing the cataclysmic forecasts that policymakers may be enabling to Breitbart’s denial of climate change’s existence all together.

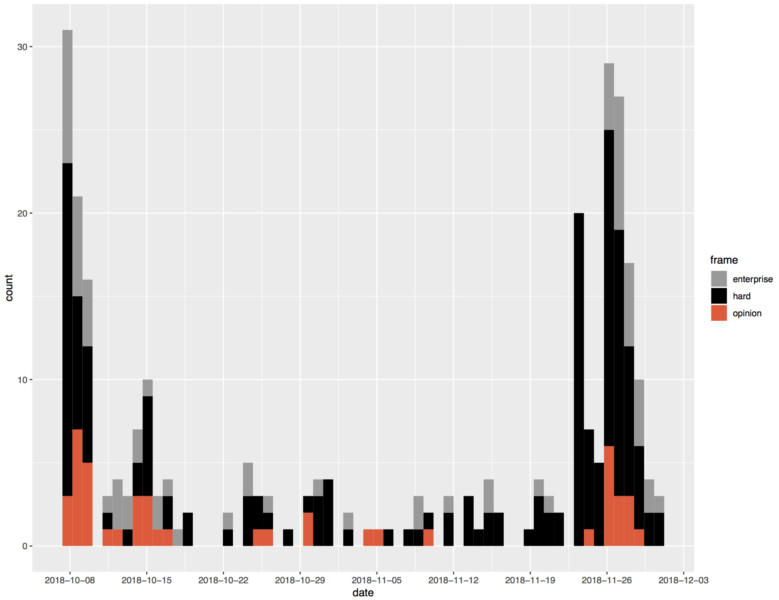

More than 30 percent of the stories released during October and November were enterprise, while 56 percent were hard or breaking news pieces. However, evident in the graph above, distribution is everything. Here’s that same information laid along the same timeline:

There are clear and unfortunate gaps in general coverage that cannot be ignored. Just one day after the IPCC report’s release, hard news coverage fell by 60 percent. After the White House report, it fell by exactly 50 percent. Similar trends for opinion and enterprise pieces followed suit: a huge spike and a giant fall. The finding here is that maybe that drop is getting smaller, which is a good thing. But the rate at which each type of coverage declined shows us that the industry isn’t generating sustainable dialogue, apart from Vox’s grief counseling piece, “How to deal with despair over climate change.”

On the other hand, media attention on the National Climate Assessment waned by only one story the following day—a less than 2 percent drop. So are we seeing that fateful wake-up call that Sullivan alluded to? It’s a dubious proposition without sustained observation. And other than the two reports central to our focus here, there’s been a lot to cover: the Camp Fire in Northern California, a human health report on climate change by the Lancet, the election of climate skeptic Jair Bolsonaro to Brazil’s presidency, and so much more.

We’re not short of big breaking-news material, that’s for sure. Then again, as global temperatures rise, more stories will appear more urgent because tragedy will be in surplus. But in the spirit of Sullivan’s wisdom, it’s our responsibility as storytellers to digest and parcel out every scrap of detail from these reports for the reader, so that we can affect the change necessary to avoid having those somewhat sexy disaster stories down the road. And we can’t stop until we’ve tipped the scale of doubt.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.