Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

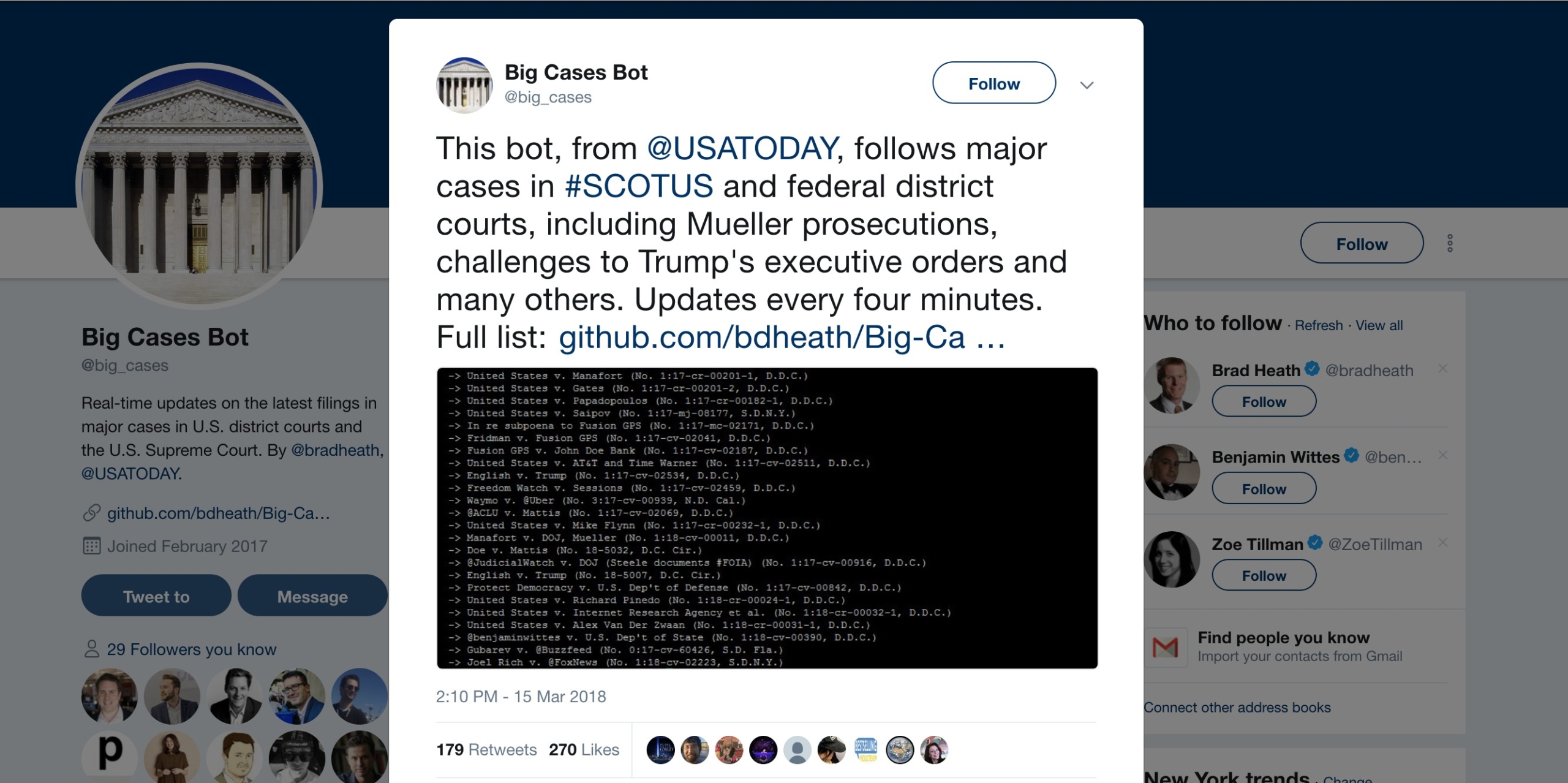

Social media bots that interact with other accounts or distribute information may be able to hold the powerful to account—automatically.

Newsrooms often use bots to connect better with their audience, but increasingly, programs that monitor public information are part of serious newswork. Whether investigating a public official about an abuse of power or a corporation skirting regulations, accountability journalism is journalism’s highest calling—and programs designed to police databases or social feeds and post their findings could help to advance those efforts.

Bots are actually fairly well-suited to accountability journalism. They can tirelessly monitor evolving sets of data, where there is data to observe—and the vigil over their subjects never falters. They can then draw the public’s attention to inconsistencies or potential misbehavior based on that monitoring, sending alerts for unexpected observations and continuously publishing updates, simultaneously reminding the powerful they are being observed. There are plenty of examples already: @newsdiffs monitors changes to news articles, @rectractionbot monitors the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) for retracted articles from medical journals, and @GVA_Watcher tracks specific types of air traffic in and out of Geneva’s airport.

https://twitter.com/retractionbot/status/1022759560564625408

A dictator's plane left #GVA airport: HZ-MF2 used by Ministry of Finance and Economy of Saudi Arabia (Boeing 737-700 VIP) on 2018/09/06 at 14:32:42 pic.twitter.com/8gO7a8Qtsg

— GVA Dictator Alert (@GVA_Watcher) September 6, 2018

To see how this type of monitoring plays out in practice—and whether it’s actually useful for holding those in power accountable—let’s consider a couple of case studies.

ICYMI: What will happen to CBS after Les Moonves leaves?

Monitoring Wikipedia with GCCAEdits

A wave of Twitter bots was launched in 2014 to monitor anonymous editing of Wikipedia pages by government officials, inspired by the @parliamentedits bot and powered by an open-source implementation. One incarnation of the bot is @GCCAEdits in Canada. It tracks anonymous edits to Wikipedia pages of Parliament of Canada, Senate of Canada, and various governmental agencies, identifying edits coming from computer addresses assigned to those organizations. The basic idea is to reveal attempts to anonymously edit pages that might obfuscate or alter the framing of official information.

Former ranks of the Canadian Force Wikipedia article edited anonymously from Canadian Department of National Defence https://t.co/2HWcTu63eU pic.twitter.com/L8gSCFCi0M

— Government of Canada Wikipedia edits (@gccaedits) August 31, 2018

Initially there was a flood of media coverage of the @GCCAEdits bot, drawing attention to the fact that it was monitoring governmental edits of Wikipedia pages. Much of that coverage used the information to reinforce a narrative of wasted government time (why should officials be editing Wikipedia to begin with?) or potential manipulation that might result from anonymous Wikipedia editing. As part of a 2016 study of the bot, researchers interviewed a government minister who confirmed he had warned staffers to beware the bot’s surveillance. After all the negative media attention, the bot started detecting fewer edits, confirming a shift in behavior.

READ: Does it actually matter that the anonymous op-ed writer said “lodestar?”

Government workers were making fewer anonymous edits. But was the bot really holding these officials accountable for bad behavior like manipulating governmental information on Wikipedia? Probably not. The same study found that much of the editing, even the anonymous stuff, was quite innocuous—only 10 percent was substantive enough to alter an entire sentence. A failure of the bot was that the behavior monitored was overly broad, including a majority of banal editing. By not being specific enough about the behavior the bot was calling out, it may have ended-up chilling otherwise harmless behavior, as well.

Anonymous sourcing at the New York Times

The @NYTAnon bot was designed to put pressure on The New York Times for its anonymous sourcing practices. The bot monitors all articles published by the Times for use of language that suggests reliance on unnamed sources. It picks up on 170 different phrases like “sources say,” or “requested anonymity,” and then tweets out an image of the offending passage with a link to the article:

A Top Syrian Scientist Is Killed, and Fingers Point at Israel https://t.co/MLNIwDv3No pic.twitter.com/jiOyqU3pci

— NYT Anonymous (@NYTAnon) August 11, 2018

Anonymous sourcing practices are a necessary part of certain types of reporting. But they do have a downside, limiting a reader’s ability to evaluate the motives or trustworthiness of information sources on their own. The key is to not overuse them, or use them sloppily just because a source is feeling a bit exposed. When Margaret Sullivan was public editor of the Times she would periodically write about the newsroom policy on anonymous sources. In fact, in her column published on January 13, 2015, she even mentioned the NYTAnon bot, suggesting at the very least that she and perhaps others in the newsroom were aware that it was drawing attention to the ongoing use of anonymous sources in the paper.

Still, despite Times’s awareness of the bot, an open question remains: Did the bot create any public pressure that might induce the Times to change its practices and perhaps clamp down on any unnecessary or frivolous anonymous sourcing practices?

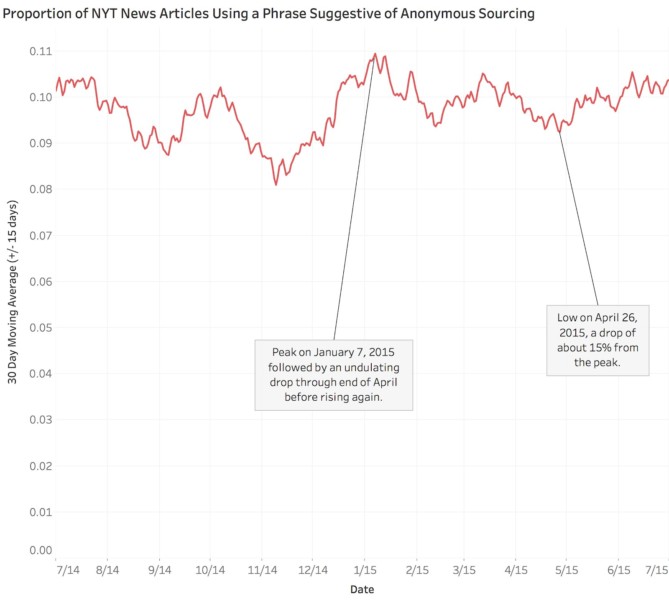

To try to answer this question I collected some data. Using the Times’s Article Search API, I ran queries to find and count all of the news articles that had used any of the 170 terms that the bot itself was tracking. For each day in my sample I divided that count by the total number of news articles published that day, giving me a proportion between 0 and 1 of stories that had used one of the phrases suggestive of anonymous sourcing. The next figure plots that data for a year using a 30 day moving average.

The NYTAnon bot started tweeting on January 5, 2015. A peak in the proportion of articles using anonymous sourcing phrases was hit on January 7th, but in the three to four months after that the use of anonymous sourcing phrases declined. By April 26, the proportion was down by about 15 percent, though after that time it began increasing again. Interestingly, there was a decline in the latter part of 2014 before a rapid rise towards November and December, just before the bot came into operation. It’s important to underscore that this data is illustrative and does not prove anything causal.

To try to determine whether the Times may have been reacting to the bot, I asked Phil Corbett, the associate managing editor for standards at the Times about the pattern. The Times uses a “broadly similar” internal method to track use of anonymous sources. According to Corbett, however, they didn’t “detect any major shift” in their estimates for the first few months of 2015. At the same time, he wasn’t able to firmly refute the possibility of a change either. The list of 170 terms I’m tracking may be more comprehensive, and therefore more sensitive, for instance.

“I will say that I don’t think much attention was paid to the Anon bot, so that seems to me unlikely to have had much effect. On the other hand, Margaret and some of the other public editors did periodically focus attention on this issue, so that could have had some impact,” Corbett added. The more likely route to accountability here was perhaps not the bot directly, but the public editor drawing attention to the issue, which in at least one instance was spurred by the bot.

Lessons for designing effective watchdog Bots

There are a few lessons to take away from these two case studies in of how to design and use bots to help with accountability journalism.

Bots may not be able to provide enough publicity or public pressure all by themselves, and so should be designed to attract attention and get other media to amplify the issue the bot exposes. And though they can absolutely change behavior, as we saw with GCCEdits, if the behavior a bot monitors is too broad, it might end up dampening other innocuous, or even productive behaviors. A good accountability bot must target the negative behavior it seeks to publicize very precisely. If bots are going to directly hold a business or person accountable for a particular behavior, they need to be designed so that they can hone in on that behavior using the available data.

Moreover, bots may have to adapt their monitoring as people change behavior or try to avoid detection via whatever data the bot is monitoring. Since bots are not actually intelligent and have no ability to adapt to a changing environment, people need to stay involved, reorienting bot attention over time. Watchdog bots should be designed to work together with people to achieve lasting accountability goals.

In summary, the most effective bots for accountability journalism will be those that can precisely target and bring to light negative behavior, draw attention via other media to increase public pressure, and then integrate humans in the loop to adapt that targeting as actors try to evade attention. We’re still in the early days of news bots, but I’m optimistic that they are and will be useful tools not only for disseminating content, but also for grander ambitions like accountability journalism.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.