Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

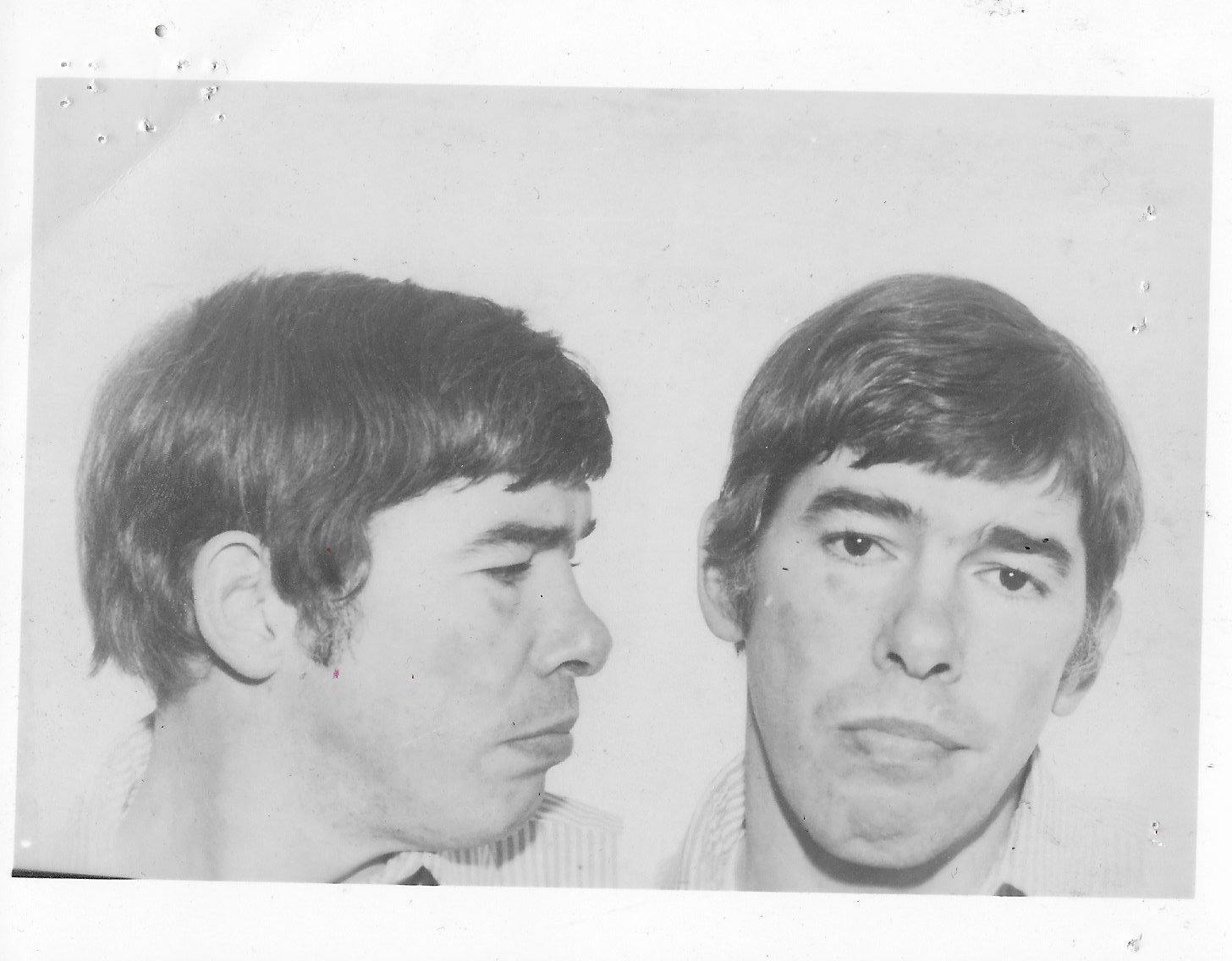

Ron Porambo was a journalist. He was an author and a visionary. He was also a robber and killer.

Freelance reporter Greg Donahue—who just published an extraordinary, near 15,000-word account of Porambo’s life in the Atavist Magazine—first heard the name last spring. Donahue grew up near Newark and was looking to peg a story to the 50th anniversary of the 1967 race riots in the city. His brother passed him Porambo’s seminal book, No Cause for Indictment—a meticulously reported account of the unrest and the deadly police response to it—which he’d picked up randomly at the Strand Bookstore. “It’s a tough to book to find,” says Donahue. “It’s essentially been erased from the canon.”

ICYMI: CNN frustrates viewers with gun comment controversy

That erasure might be why one of the stranger journalism stories in known history slipped off the mainstream record. Or, that strange journalism story may itself have caused the erasure. Porambo immersed himself in the underworld milieux of ’60s and ’70s America—living among, and telling the stories of, marginalized civilians and criminals alike. “He wrote about the B-girls, and prostitutes, and bootleggers, and drug addicts, and homeless people,” Donahue says. “And he moved in that world outside of reporting also. These were the people he hung out with.”

At some point, however, the lines between reporter and subject blurred, and Porambo himself turned to a Hollywood-worthy life of crime.

He took to robbing drug dealers, and his behavior became increasingly unhinged. In 1978, while working in Canada, he mugged a Toronto airport parking attendant with a toy gun. Back in Newark in the early 1980s, the stickup routine became a habit—with fake guns and with real ones. In 1983, he donned a prop mustache and (with an accomplice) burst into a cocaine dealer’s house; a scuffle ensued, and Porambo ended up killing the dealer. About a month later, Porambo himself was shot in the head while sitting in his car. He survived, but would spend the rest of his life in prison, where he died in 2006.

At some point, the lines between reporter and subject blurred, and Porambo himself turned to a Hollywood-worthy life of crime.

Donahue, hooked less by Porambo’s book than by his personal story, set out to tell it in greater detail. When editors he pitched said they didn’t see it fitting a short word count, Donahue dug deeper. He sought out Porambo’s wife, Carol, and her daughter, Glenna—making contact, after a slew of dead-end cold calls, via the publisher that reissued Porambo’s book on the 40th anniversary of the Newark riots in 2007. Glenna invited Donahue to Kingsport, Tennessee, where she and her mother now live. “I got the feeling she was waiting for someone to call,” Donahue says. “She knew how crazy his story was, and that the book was important, and was waiting for someone to figure it out.”

The Tennessee trip helped Donahue shed light on a particularly strange chapter of Porambo’s life that followed the 1971 publication of No Cause for Indictment. By this point, Porambo had been charged with bribing a cop to get photos for the book—he was later found guilty and served three months in jail. In early 1972, Porambo was shot in both legs in his car. He claimed he’d been targeted for exposing “police murders” and city corruption. Officers speculated he’d orchestrated the shooting himself to get book publicity—after the incident, his publisher secured an ad in The New York Times that screamed, “THEY TRIED TO MURDER THE AUTHOR.”

“I went into [the reporting] initially believing he had just been shot. That was the line I read in the papers,” Donahue says. “But I interviewed more people, [including] some of the folks [from] the TV show he was working on at the time, and they expressed having some doubts about the situation.” His interview with Carol offered further evidence of a stitch-up: She recalled hearing Porambo conspire with a friend right before the incident. “It was sort of a coup for me,” says Donahue. “Again, it’s still sort of conjecture. [But] the real point is that anything was possible with him.”

Freelance reporter and filmmaker Greg Donahue (courtesy photo).

That the story seems plausible strikes at a central contradiction in Porambo’s character. He was a dogged beat reporter who, by all accounts, cared deeply about exposing injustice—he styled himself after swashbuckling New York tabloid giant Jimmy Breslin, was a devotee of the “New Journalism” style that broke boundaries in his era, and hoped to follow in the footsteps of Carl Bernstein, who’d jumped to The Washington Post from one of Porambo’s papers, the Elizabeth Daily Journal. At the same time, he was a notoriously prickly edit, and prone to cruel moods.

Even after his spell behind bars for bribery, Porambo continued to get journalism jobs: During a later sentence for robbery he even picked up parole work at the Atlantic City Press. Donahue reckons Porambo’s rare access to certain communities—while Porambo was white Carol is black, and the couple lived in black neighborhoods—made him a valuable newsroom commodity in spite of his erratic behavior.

Ultimately, however, no editor could discipline Porambo’s mercurial streak. And Porambo himself seemed to sour on the world of journalism. Donahue says he felt betrayed that other reporters didn’t stick up for him during his bribery trial, and was left embittered when No Cause for Indictment was overlooked for a Pulitzer.

The book was a prescient early contribution to an important strain of social justice journalism. When it was reissued, the New Jersey poet and activist Amiri Baraka said of it, “It was a reference point….One had to be able to say, ‘Yes, I know that book,’ whether you had read it or not.” Its second publisher, meanwhile, told the Newark Star-Ledger, “In some ways, Ron’s life really depicts the tragic trajectory of the city of Newark. It had so much wasted promise. But his life also had this one great piece of work….If you accomplish one great thing like that in your life, is it really a wasted life?”

“She knew how crazy his story was, and that the book was important, and was waiting for someone to figure it out.”

No Cause for Indictment recalls another question that has become all too familiar: Can important works be separated from the personal ethics of their creators? Donahue says the dilemma played on his mind while he reported the piece. “I think the book is absolutely relevant and absolutely instructive to what’s happening today, to a better understanding of the context of police relations with the black community,” he says. “But at the same time, I don’t think you can separate the art and artist. No conversation of Ron Porambo’s work is complete without also examining what became of his life.”

Ultimately, Porambo’s journalism, complex character, and scarcely believable fate should be tackled together because they were intertwined parts of a complicated, yet inseparable, whole. “He was stubborn and full of outrage,” says Donahue. “When he had a vehicle for it, which was reporting, the result was something like No Cause for Indictment. And when he didn’t have a vehicle for it, the result was the rest of his life, which was obviously violent and kinda dangerous.”

ICYMI: The story BuzzFeed, The New York Times and more didn’t want to publish

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.