Sign up for The Media Today, CJR’s daily newsletter.

Hilde Lysiak hopped on her bike and pedaled south past the old Selinsgrove Inn, past the farmers market with the Amish couple selling home-grown veggies and pies, past the local police station where no one was around to answer the door, and over the green truss bridge above Penns Creek before hanging a right onto a shady road that hugs the river. It was a brilliant July Saturday morning in Selinsgrove, a quaint hamlet of about 5,000 in Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna River Valley, where Hilde publishes Selinsgrove’s only monthly newspaper, The Orange Street News.

Today was Selinsgrove’s sixth annual Ta-Ta Trot, a 5K that drew some 2,100 runners and raised more than $71,000 to fight breast cancer—a feel-good story, for sure, but Hilde wasn’t interested. There was hard news to chase.

Two days earlier, a small tornado had torn through town, toppling trees and scattering debris. The street along the river caught the brunt of it, and Hilde had come to survey the damage. She parked her bike, whipped out her Moto G Android smartphone, and started snapping pictures of downed branches and limbs. Then she walked up to a white ranch house and knocked on the door.

An older man with an ample potbelly answered, and apologized for being shirtless. With a mix of affability and confusion, he looked down at the freckly blonde 8-year-old standing before him. She had her pen and pad in hand. Homemade press credentials dangled from her neck. “Hi. I’m Hilde from The Orange Street News, and I was wondering if you could tell me what happened a couple nights ago.”

He gestured to his neighbor’s property. “This gentleman over here got the worst of it,” he said. “It went through his house and then went out in the middle of the Susquehanna River and went to the south.” Hilde took notes. She asked the man for his name and spelled out the letters in her notebook: “B-O-B M-A-Y-H-E-W.”

She walked next door, where a bearish tattooed guy in a white tank top and shorts was outside working on his boat. “The wind kicked up like that,” he said, snapping his fingers. “Out of nowhere. It started to rain really, really hard. The next thing you knew, the trees from both sides of the road were blowing down. Ten seconds later, as quick as it came, it was all over.”

“Was anybody hurt?” Hilde asked.

“Nope. Within 10 minutes, I heard chainsaws abuzz and everybody was getting their stuff back in order. I lucked out real good.”

Hilde walked back to her bike and smiled. “That went really well!”

For an industry with an uncertain future, where newspapers and newspaper jobs have been disappearing like a species on the road toward extinction, where “reporter” tends to rank low on the list of desirable careers, it feels refreshing to see someone so young so interested in journalism. But Hilde isn’t just another precocious kid with a hobby. She attends town meetings. She covers crime without the police department’s cooperation. She shows up at the scenes of breaking news events. Sure, Hilde’s far from being a pro, but she still provides a public service in a town without a dedicated local news outlet.

Her newspaper began as a family digest written by hand for her parents and siblings. (Children have been making such publications for as long as crayons and scrap paper have existed.) Then, Hilde explained the night before she went out on her reporting assignments for the August issue, “I realized it wouldn’t get me anywhere.” She told her father, Matt Lysiak (that’s lee-shak), a 37-year-old journalist and former New York Daily News reporter, that she wanted to do a newspaper for real. The deal was that Hilde would be responsible for all the story ideas, writing, reporting, and photography. Matt would be her editor and handle the typing, layout, and printing. Every month, the HP 7110 in his third-floor home office spits out hundreds of pages. “I love it,” Hilde says.

She caught the journalism bug from her father, watching with awe and excitement as he hustled for New York’s “hometown newspaper.” She’s drawn to the profession for the same reason lots of reporters are: It’s a license to ask people nosy questions and get them to tell you things. Hilde says she loves doing interviews and coming away with “all this information.” Near term, she says, “I just want to do as many issues as possible and I want to expand. I want more people reading it.” Long term, her goals are loftier. “I don’t really want to work for a newspaper. I want to do my own. I kind of want it to become as big as the Daily News one day.” For locals, it may seem more novelty than pillar of the Fourth Estate. But if Hilde were to stick with it, The Orange Street News could evolve into something more meaningful. “People think it’s cute,” says Selinsgrove borough president Brian Farrell. “As far as being taken seriously or competing with other newspapers, I don’t know if I’d go that far. But hopefully in the future it will. She could turn it into whatever she wants.”

The Orange Street News, which debuted last December as a full-color, four-page digest folded on 11- by 17-inch sheets, was named for the street where Hilde lives in a former bed and breakfast with her mom and dad, her three sisters, and the family’s two mutts, Bismarck and Archie. It’s an impressive enterprise for someone who’s barely cracked the third grade. “All the News Fit For Orange Street,” reads the paper’s New York Times-inspired slogan. (Hat tip to Matt for that one.)

Two hundred copies of each issue are distributed around town in local businesses, like a cafe where Hilde is known to hunker down on deadline with her usual toasted bagel and side of bacon. More than 40 people pay $1 to $2 a year to have Hilde hand-deliver The Orange Street News to their doors, many of whom the Lysiaks had never heard of before subscription letters began arriving in the mail. “We are very proud of you for taking on such a big project at such a young age,” wrote Mike Garinger, who enclosed an additional $5 to help with production costs. “We look forward to new issues,” wrote Susquehanna University education professor Anne Reeves. In particular, Reeves is a fan of the recurring short story on page 2. (Recent installments: “Dolls in the Attic”; “Elephant Makes a Friend.”) “The fiction she writes is creative and sometimes spooky and somewhat dark, always interesting,” Reeves told me over email.

Hilde wants to increase circulation so she can start selling advertising. Don’t laugh—a member of the local swimming pool’s board of directors told Matt that when the pool’s ad budget was discussed at a meeting this summer, The Orange Street News came up as a publication in which they should advertise. Apparently, board members were familiar with the News, but not all of them knew it was made by a kid.

Aside from The Orange Street News, Selinsgrove and its neighboring communities are covered by several small media outlets. There’s wkok, a radio station that broadcasts out of nearby Sunbury at frequency AM 1070. There’s also The Snyder County Times, a free weekly that appears to be a repository for press releases, municipal announcements, and calendar blurbs. The area’s newspaper of record is The Daily Item, a 78-year-old broadsheet serving roughly 20,000 print readers in the Central Susquehanna Valley. Hilde’s 11-year-old sister, Izzy Lysiak, is the Item’s kids columnist, having successfully pitched “Ask Izzy” as a must-read for the under-13 set. She gets paid $25 a week.

Hilde’s publication—its 8-year-old worldview notwithstanding—is replete with the type of hyperlocal headlines that grace the pages of small-town periodicals the world over: a fundraiser for a neonatal intensive care unit; a new music store on Selinsgrove’s picturesque main drag; a local kindergarten teacher who won the 35th Long Island Marathon. They’re shorter than what you’d expect to see in a professional neighborhood newspaper, but they do the trick.

It’s not all softball. In June, after Hilde’s competitors reported there had been a break-in on Orange Street, Hilde paid a visit to the police station to ask for the address. The cops wouldn’t give it out, so she went knocking on doors until she found the right house. Hilde landed an interview with its resident, who gushed that her dog, Zeus, had saved the day: “Hero Dog Thwarts Intruder!” Hilde’s headline proclaimed. As for the perpetrator, Hilde dubbed him (or her) “The Orange Street Bandit.”

About a month earlier, on the evening of May 4, Hilde got her first taste of breaking news when she learned there was a fire raging at a nearby church. She raced over with her pen and notebook. “It could have been a lot worse,” a firefighter told her at the scene. “But we are all glad there were no people inside.”

Judging by the front page of the April issue, a career in media reporting might be in store. “Print is dead—at least at Selinsgrove High School,” Hilde wrote. “Journalism students at Selinsgrove say they would like a printed paper but there isn’t enough money in the budget.” Matt told me Hilde got tipped to the story when she was at the local cafe talking to a high school girl she’s friendly with. Superintendent Chad Cohrs pushed back, telling Hilde: “An electronic version can be done more frequently and with more current information than a paper version. For those who still want a paper version, I would suggest they hit the print button on their computers.”

The Orange Street News traffics heavily in earnest community journalism. But it also exudes a certain garishness that seems natural for someone who grew up visiting tabloid newsrooms and accompanying her father on stakeouts. Exclamation points and “exclusives” abound. Hilde makes sure to have eyeball-grabbing images for “the wood.” Nor did she hesitate to float a reader-submitted photo of a “mystery beast” that was supposedly spotted in a local park. Her July issue featured an exposé on Piano Palooza, in which visitors to Selinsgrove’s picturesque downtown were invited to play artistically refurbished pianos positioned among the stately brick colonials on Market Street. “Selinsgrove Piano Palooza is hitting all the wrong notes,” Hilde reported in a story headlined “A Real Piano Pa-Loser: Orange Street News Investigation Reveals Pianos Don’t Play.” The article continued: “On seven of the fourteen pianos its [sic] impossible to even push some of the keys down.” Matt admits to jazzing up the headlines and throwing in some tabloid flair, but that’s to be expected of any editor worth his salt, and it’s a valuable lesson for any aspiring newswoman.

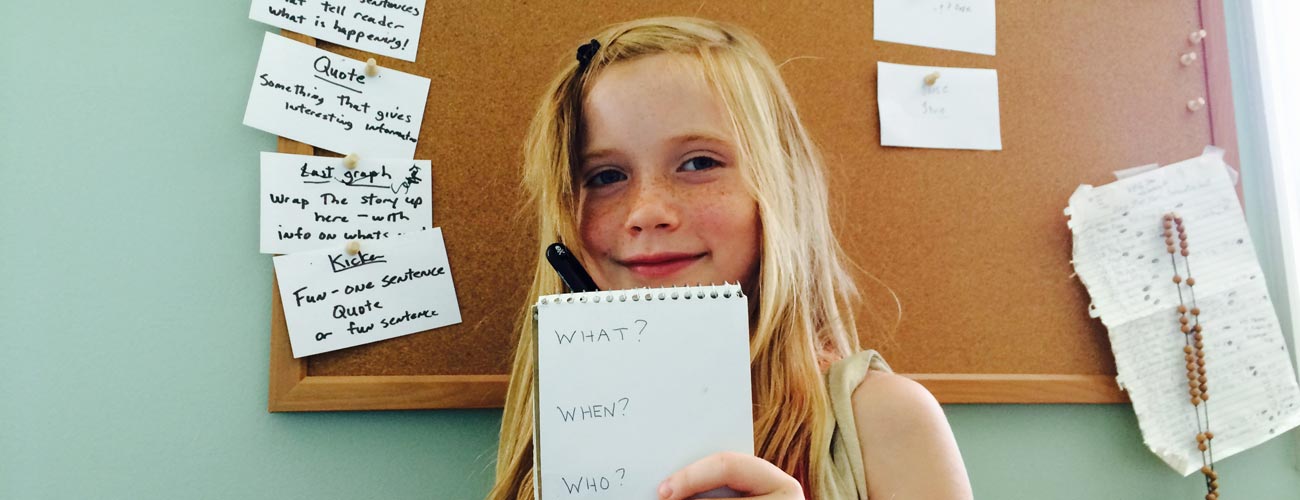

Hilde picked up everything she knows about reporting from her father. Matt taught her things like how to structure a news story, what a “lede” is and why you need a “nut graph.” She listens to him interview people when he’s working on freelance assignments. When she comes back from a reporting assignment of her own, they talk it over. There’s a bulletin board in his office with index cards mapping out what stories she’s working on for each issue. If he thinks one of her ledes is no good, he tells her so, and either tightens it up himself or works with Hilde to make it better. As much as possible, though, Matt tries to let Hilde stay in the driver’s seat. “The minute I get too involved,” he says, “it’s not a kid’s paper anymore.”

Matt lysiak was 19 when he dropped out of high school in 1997, after recovering from cancer, to start his first newspaper—a tabloid that “attempted to tackle local corruption,” as he now puts it, in his hometown of Danville, about 20 minutes northeast of Selinsgrove. It was called The Danvillian, a framed copy of which hangs on the wall of Matt’s study, along with various Daily News front pages carrying his byline. To bankroll the paper, Matt took a job waiting tables at a nearby Denny’s. One day, a young woman named Bridget walked in and ordered a coffee. It was practically love at first sight. They moved to New York together later that year so Matt could pursue journalism. (The wedding followed in April 2003.) They settled down in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, where Matt started yet another small independent newspaper. That publication, The Bay Ridge Conservative, caught the eye of Gersh Kuntzman, then editor-in-chief of The Brooklyn Paper. Kuntzman offered Matt a job. “The paper was filled with preposterous neo-con musings, but I could see from how it was put together that Lysiak was a serious newspaperman,” recalls Kuntzman, now an editor at the Daily News. “I could tell he was going places.”

Matt jumped to the Daily News in 2006. He was the guy who’d parachute in whenever the editors needed someone to, say, trail Chelsea Clinton on her holiday in Martha’s Vineyard, or rush to the scene of Trayvon Martin’s killing in Florida. In late 2012, Matt covered the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. He spent the next four months reporting on the aftermath, churning out enough scoops and front-page stories to land him a book deal for Newtown: An American Tragedy, which Simon & Schuster published around the time of the one-year anniversary. By then, he’d left the News and moved his family out to the country.

Hilde misses New York. “There’s barely any news around here,” she says. “There’s never any crazy murders. In New York, it’s like there was something every day.” Then again, Selinsgrove’s sleepiness and walkability is the reason Matt and Bridget are comfortable letting Hilde traipse around town on her own. “There are some people who probably feel like we’re really irresponsible parents,” says Matt.

When news does happen in Selinsgrove, it tends to be about robberies or other small-bore crime. Last year, a home security company released data appearing to show that Selinsgrove was Pennsylvania’s seventh most dangerous city, ahead of Philadelphia at No. 8. Locals scoffed, claiming the report was cooked up as a marketing ploy. “Selinsgrove is probably one of the safer places,” one resident (who happened to be a local gun-shop owner) told The Daily Item. Farrell, the borough president, describes Selinsgrove as the type of vestigial American idyll where people still leave their doors unlocked—an occasional break-in like the one Hilde covered notwithstanding. “It’s a very safe community,” Farrell said in an interview.

That’s lucky for Hilde, because she seems to thrive when pounding the pavement. It’s part of her dna. In a funny twist, she even shares a first name (though not the same spelling) with Hildy Johnson, the investigative reporter in Howard Hawks’s 1940 screwball comedy, “His Girl Friday.” (Total coincidence, says Matt, though he watched the film with Hilde for the first time recently; there is now a “His Girl Friday” poster hanging in her bedroom.) Hilde is also known for asking heady questions apropos of nothing. “Is the sun really going to burn out one day?” “What does it mean to be radioactive?” “Do you know what my biggest fear is? That people can read my mind.”

“She wants to talk, and she wants to talk about meaningful things,” says Bridget. “It comes from a sincerely curious place,” adds Matt.

That curiosity took Hilde back to the center of town after she wrapped up her tornado interviews. She rode her bike west to an interview at the Selinsgrove Dance Studio, a small New Yorker tote dangling from the right handlebar. (The tote bag used to be Bridget’s, although Hilde said she’s flipped through the magazine once or twice.) Next stop was the police station to see if there were any updates on the elusive Orange Street Bandit. (No dice.)

Afterwards, Hilde popped into a local diner for a late breakfast. She ordered a large pancake, opened up her notebook and started working on an outline of the storm story: “Lead. Nut. Quote. Kicker.” A man with a close-cropped gray beard and glasses was sitting at the table to Hilde’s left. Hilde didn’t know him, but he leaned in and asked, “Are you working on your next edition?”

Meet Mayor Jeff Reed. He’s a 63-year-old painter halfway through his second year as the town’s top elected official, and while he may not enjoy dealing with reporters, he’s gotten used to that part of his job. Unsurprisingly, Reed said Hilde was the youngest reporter he’d ever encountered. He thinks she’s good for her age. “I saw her paper before she came to her first meeting,” he said. “I thought it was very well done.”

I told Mayor Reed that Hilde needs to learn how to interact with vips like him, to ask the right questions, and to get the information she needs. What wisdom might Reed impart to his community’s youngest working journalist? He paused to think about it, then looked down at Hilde, who was busy writing about those uprooted trees. “To report the news, not try to create the news,” he said.

Hilde nodded. Before getting up to leave, the mayor agreed to be interviewed at some point. A few minutes later, by the time her last bite of pancake had disappeared, Hilde’s first draft was complete.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.