On these pages the Review reproduces the words of men who were in the Presidential party in Dallas on November 22. The words are offered in a connected narrative as a case study in the reflexes and conscious actions of professional journalists under the heaviest kind of pressure and emotional stress. Several of these narratives have been widely distributed, but they have not been previously collaged. They emphasize again how little there was for reporters to see and how much, after the first phases, they depended on each other to complete their information.

MERRIMAN SMITH, United Press International I was riding in the so-called White House press “pool” car, a telephone company vehicle equipped with a mobile radio telephone. I was in the front seat between a driver from a telephone company and Malcolm Kilduff, acting White House press secretary for the President’s Texas tour. Three other pool reporters were wedged in the back seat.

Malcolm KILDUFF I had just finished saying to the representative of UPI, “Would you mind telling me what in the name of heaven the Texas School Book Repository is? I never heard of a school book ‘repository.’ ” With that we heard the first report.

JACK BELL, The Associated Press There was a loud bang as though a giant firecracker had exploded in the cavern between the tall buildings we were just leaving behind us.

ROBERT E. BASKIN, Dallas Morning News “What the hell was that?” someone in our car asked. Then there were two more shots, measured carefully.

BOB JACKSON, photographer, Dallas Times-Herald First, somebody joked about it being a firecracker. Then, since I was facing the building where the shots were coming from, I just glanced up and saw two colored men in a window straining to look at a window up above them. As I looked up to the window above, I saw a rifle being pulled back in the window. It might have been resting on the window sill. I didn’t see a man.

BELL The man in front of me screamed, “My God, they’re shooting at the President!”

RONNIE DUGGER, The Texas Observer “What happened?” a reporter called out inside the bus ahead of me. Through the windows we saw people breaking and running down Elm Street in the direction of the underpass, and running to the railing of the arch at the foot of the downtown section and leaping out of our sight onto the grass beyond and below. . . . We speculated someone might have dropped something onto the motorcade from the overpass. I saw an airplane above the area and wondered if it might have been dropping something.

JERRY TER HORST, Detroit News There was a great clamor in the bus, “Open the doors. Let us out,” but the bus speeded up, and it was impossible. The doors were not opening, and obviously the driver was staying with the police escort.

SMITH Everybody in our car began shouting at the driver to pull up closer to the President’s car. But at this moment, we saw the big bubble-top and a motorcycle escort roar away at high speed. We screamed at our driver, “Get going, get going.” We careened around the Johnson car and its escort and set out down the highway, barely able to keep in sight of the President’s car and the accompanying Secret Service follow-up car.

TOM WICKER, The New York Times Jim Mathis of The Advance (Newhouse) Syndicate went to the front of our bus and looked ahead to where the President’s car was supposed to be, perhaps ten cars ahead of us. He hurried back to his seat. “The President’s car just sped off,” he said. “Really gunned away.” . . . The press bus in its stately pace rolled on to the Trade Mart, where the President was to speak.

SMITH I radioed the Dallas bureau of UPI that three shots had been fired at the Kennedy motorcade.

LEONARD LYONS in the New York Post The other reporter kept demanding the phone, and tried reaching over Smith’s shoulder to grab it. Smith held on, telling his desk, “Read the bulletin back to me.” The other pool reporter started . . . clawing and pummeling Smith—who ducked under the dashboard to avoid the blows. Smith held on to the phone, dictating and rechecking the bulletins. Just before the car pulled up at the hospital, Smith surrendered the phone.

BELL I grabbed the radiophone, got the operator, gave the Dallas bureau number, heard someone answer. I shouted that three shots had been fired at the President’s motorcade. The phone went dead and I couldn’t tell whether anyone had heard me. Frantically, I tried to get the operator back. The phone was still out.

BASKIN We began to suspect the worst when we roared up to the emergency entrance of Parkland Hospital. The scene there was one of sheer horror. The President lay face down on the back seat.

“We talked anxiously, unbelieving, afraid.”

BELL We were turning into the emergency entrance to the hospital when I hopped out to sprint for the President’s car. The first hard fact I had that the President was hit was when I saw him lying on the seat. Because he was face down, I asked a Secret Service man, to make doubly certain, if this was the President, and he said it was. He said he didn’t think the President was dead.

SMITH I knew I had to get to a telephone immediately. Clint Hill, the Secret Service agent in charge of the detail assigned to Mrs. Kennedy, was leaning over into the rear of the car. “How badly was he hit, Clint?” I asked. “He’s dead,” Hill replied curtly. . . . I raced down a short stretch of sidewalk into a hospital corridor. The first thing I spotted was a small clerical office, more of a booth than an office. Inside, a bespectacled man stood shuffling what appeared to be hospital forms. At a wicket much like a bank teller’s cage, I spotted a telephone on the shelf. “How do you get outside?” I gasped. “The President has been hurt and this is an emergency call.” “Dial nine,” he said, shoving the phone toward me. It took two tries before I successfully dialed the Dallas UPI number. Quickly I dictated a bulletin.

Litters bearing the President and the Governor rolled by me as I dictated, but my back was to the entrance of the emergency room about 75 or 100 feet away. I knew they had passed, however, from the horrified expression that suddenly spread over the face of the man behind the wicket.

SAUL PETT in AP Log In the AP Dallas bureau, Bob Johnson was just returning to his desk. Executive Editor Felix McKnight called from the Times-Herald newsroom: “Bob, we hear the President has been shot, but we haven’t confirmed it.” Johnson raced for his typewriter. Staffer Ronnie Thompson told him: “Bell tried to call a minute ago but he was cut off.” Johnson wrote the dateline of a bulletin. He had just reached the dash that follows the AP logotype when the phone rang again. It was staffer James W. Altgens, a Wirephoto operator-photographer known to everyone as “Ike,” on duty as a photographer several blocks from the office. . . .

“Bob, the President has been shot.”

“Ike, how do you know?”

“I saw it. There was blood on his face. Mrs. Kennedy jumped up and grabbed him and cried, ‘Oh, no!’ The motorcade raced onto the freeway.”

“Ike, you saw that?”

“Yes. I was shooting pictures then and I saw it.”

With the phone cradled to his ear, Johnson’s fingers raced.

ROBERT DONOVAN, Los Angeles Times We went to the Trade Mart, and the first thing we wanted to do was look for the President’s car, and we didn’t find it. But even then it didn’t raise any positive proof in my mind, because there were a number of entrances to this Trade Mart. . . . Then it became obvious something had happened. We ran into this merchandise mart, which is an utter maze. We filed into the corridor of this hall, and the waiters were bringing out filet mignon to an utterly unsuspecting audience, and they told us, to make matters utterly worse in our haste, that the press room was on the fourth floor. So, of course, what were there but escalators? So up we go, and we ran into the press room and it was sort of like air currents. We were all going around in a pattern of least resistance.

DUGGER In the alarm and confusion, the reporters were full of doubt, and some were a little panicky. No one wanted to say what he was not sure of. Reporters had their editors on the phone and nothing definite to tell them.

SID DAVIS, Westinghouse Broadcasting Company I phoned to Washington saying, “Something has happened.”

DUGGER I went from reporters at telephones who did not know and asked me frantically what I knew—I went on a run to a group of four or five who were gathered around M. W. Stevenson, chief of the criminal investigation division of the Dallas police. “The President was hit, that’s our information at present.” He had been taken to Parkland. How badly hurt? “No, sir, I do not know.”

WICKER At the Trade Mart, rumor was sweeping the hundreds of Texans eating their lunch. It was the only rumor I have ever seen; it was moving across that crowd like a wind over a wheatfield. A man eating a grapefruit seized my arm as I passed. “Has the President been shot?” he asked. “I don’t think so,” I said. “But something happened.”

TOM KIRKLAND, managing editor, Denton Record-Chronicle The rumor started spreading here (at the Trade Mart) about 12:45 p.m., but nobody believed it. Everyone just stood around in disbelief. At about 1 p.m. it was announced that there had been a mishap during the parade. Everybody had finished eating. He told them that the mishap was not serious, but there would be a delay in the President’s address.

WICKER With the other reporters—I suppose 35 of them—I went on through to the upstairs press room. We were hardly there when Marianne Means of Hearst Headline Service hung up a telephone, ran to a group of us and said, “The President’s been shot. He’s at Parkland Hospital.” One thing I learned that day; I suppose I already knew it, but that day made it plain. A reporter must trust his instinct. When Miss Means said those eight words—I never learned who told her—I knew absolutely they were true. Everyone did. We ran for the press buses.

DONOVAN A man I took to be a Dallas radio station man said to me that the President had been shot and may be dead. Well, it was stupefying, utterly stupefying. We had just seen him in the bright sunshine with his wife. . . . Then there was a great clamor of “Where is he? Where is anybody? Where is the President?” This Dallas radio man went to a policeman and came back and said he was in Parkland Hospital. I said, “How can we get there?” and he said, “I have a station wagon. Come on. I will take you.” By this time we were all running back through the dining hall before the startled diners, and Tom Wicker, of The New York Times, was grabbed by the head waiter, who said, “Here, you can’t run in here.” Wicker just ran over him.

WICKER I pulled free and ran on. Doug Kiker of the Herald Tribune barreled head-on into a waiter carrying a plate of potatoes. Waiter and potatoes flew about the room. Kiker ran on. He was in his first week with the Trib, and his first presidential trip.

KIRKLAND At 1:07, Eric Johnsson announced in a very, very trembling voice: “I’m not sure that I can say what I have to say. I feel almost as I did on Pearl Harbor day.” At that point his voice broke. Then he announced that the President and the Governor had been shot. . . . It was quiet.

DONOVAN Peter Lisagor, of the Chicago Daily News, and I and some other reporters got into a station wagon with his radio man and we went out of the Trade Mart at a breakneck clip with his horn blaring, through traffic, through lights. It was a horrifying ride.

WICKER I barely got aboard a moving press bus. Bob Pierpoint of CBS was aboard and he said that he now recalled having heard something that could have been shots— or firecrackers, or motorcycle backfire. We talked anxiously, unbelieving, afraid.

DAVIS I went to a policeman and said, “You’ve got to get me to Parkland Hospital,” and he said: “Buddy, all the cars are gone. We have nothing available here to get you anyplace.” I said, “You have got to get me there. I am a member of the White House Press,” or something of that sort. I insisted. He stammered that he had no vehicles for me, but he stood out in the middle of the freeway and stopped a car. It was about a 1948 Cadillac driven by a Negro gentleman, and the policeman said, “Get this man to Parkland Hospital right away.” This fellow said, “Yes, sir.” . . . He hit the accelerator on that car, and I nearly went through the back end, and I shouted up front to him and said, “Sir, we both want to get there. Take it easy.”

DONOVAN As we approached the hospital on a double-lane highway, the radio-station man saw traffic piling up ahead of him, so he turned in and went against the approaching traffic, some of it approaching at high speed, horn blowing. Well, the police had seen this station wagon coming up the wrong end of the street with its horn blowing, assumed it was full of officials, and stopped all traffic and waved us into the hospital grounds.

WICKER At its emergency entrance stood the President’s car, the top up, a bucket of bloody water beside it. Automatically, I took down its license number—GG300 District of Columbia.

DUGGER In the hospital I heard people who work there saying, “Connally, too.” “It’s a shame, I don’t care who it is.” No one knew who was alive or who was dead. At the emergency entrance, Senator Ralph Yarborough, terribly shaken, gave the first eyewitness account that I had heard. He had been in the third car, with the Vice President and Mrs. Johnson; removed from the President’s car by the one filled with Secret Service men.

WICKER The details he gave us were good and mostly—as it later proved—accurate. But he would not describe to us the appearance of the President as he was wheeled into the hospital, except to say that he was “gravely wounded.” We could not doubt, then, that it was serious. I had chosen that day to be without a notebook. I took notes on the back of my mimeographed schedule of the two-day tour of Texas we had been so near to concluding. Today, I cannot read many of the notes; on November 22, they were as clear as 60-point type.

DUGGER Because I had reached Yarborough first before many of the reporters came up, I then told a group of them what he had said from the first. This was a common scene the rest of the day, reporters sharing what they had learned with their colleagues.

WICKER Mac Kilduff came out of the hospital. We gathered round and he told us the President was alive. It wasn’t true, we later learned; but Mac thought it was true at that time, and he didn’t mislead us about a possible recovery . . . Kilduff promised more details in five minutes and went back into the hospital. We were barred. Word came to us second-hand—I don’t remember exactly how—from Bob Clark of ABC, one of the men in the press “pool” car near the President’s, that he had been lying face down in Mrs. Kennedy’s lap when the car arrived at Parkland. No signs of life . . . I knew Clark and respected him. I took his report at face value, even at second-hand. It turned out to be true.

KILDUFF At 1:04 they were still trying to work on him, as . . . Dr. Perry’s statements have subsequently indicated. It was only a few minutes later, however, that in talking to Kenney O’Donnell (White House Appointments Secretary) that we knew the President was, in fact, dead. . . . About 10 or 15 minutes after 1:00 I got hold of Kenney and I said, “This is a terrible time to have to approach you on this, but the world has got to know that President Kennedy is dead.” He said, “Well, don’t they know it already?” and I said, “No, I haven’t told them.” He said, “Well, you are going to have to make the announcement. Go ahead. But you better check it with Mr. Johnson.”. . . His (President Johnson’s) reaction was immediate on that. And he said, “No, I think we better wait a minute. Are they prepared to get me out of here?”. . . By this time it was about 1:20. I went back and talked to President Johnson, and I said, “Well, I am going to make the announcement as soon as you leave.”. . . Then the two of us, President Johnson and myself, walked out of the emergency entrance together, and everyone was screaming at me, “What can you tell us?” It was a scene of absolute confusion.

DUGGER Reporters trying to make phone calls found that all the hospital phones had gone dead. I chased across the street to find a phone in a filling station to call the paper I was working with. While I was standing in the storeroom where the phone was, waiting to get through, I heard it announced on the radio, “The President is dead.” I told the editor and rushed back to the hospital. I first believed and comprehended that he was dead when I heard Doug Kiker of the Herald Tribune swearing bitterly and passionately, “Goddam the sonsabitches.” Yes, he was dead. But who had announced it? In the press room that had been improvised out of a classroom, no one seemed to know.

WICKER When Wayne Hawks of the White House staff appeared to say that a press room had been set up in a hospital classroom at the left rear of the building, the group of reporters began struggling across the lawn in that direction. I lingered to ask a motorcycle policeman if he had heard on his radio anything about the pursuit or capture of the assassin. He hadn’t, and I followed the other reporters. As I was passing the open convertible in which Vice President and Mrs. Johnson and Senator Yarborough had been riding in the motorcade, a voice boomed from its radio: “The President of the United States is dead. I repeat—it has just been announced that the President of the United States is dead.” There was no authority, no word of who had announced it. But—instinct again—I believed it instantly. It sounded true. I knew it was true. I stood still a moment, then began running. . . . I jumped a chain fence looping around the drive, not even breaking stride. Hugh Sidey of Time, a close friend of the President, was walking slowly ahead of me. “Hugh,” I said, “the President’s dead. Just announced on the radio. I don’t know who announced it but it sounded official to me.” Sidey stopped, looked at me, looked at the ground. I couldn’t talk about it. I couldn’t think about it. I couldn’t do anything but run on to the press room. Then I told the others what I had heard. Sidey, I learned a few minutes later, stood where he was a minute. Then he saw two Catholic priests. He spoke to them. Yes, they told him, the President was dead. They had administered the last rites.

DUGGER Then it was that Hugh Sidey of Time came in and, his voice failing with emotion, told the assembled press that two Catholic priests had told him and another reporter or so that the priests had given the President the last rites.

TER HORST I had just paid somebody in the hospital, a nurse’s aide or somebody, $15 to keep a line open to Detroit. . . . I ran down through the corridor and Hugh Sidey . . . was saying, “I have just talked to Father Huber and he said, ‘He is dead, all right.’ ” I ran back down the corridor to the telephone, to relay this to my office in Detroit, and I couldn’t talk. The girl who had kept the line open for me went and got a little paper cup of water. When I said over the telephone what Father Huber had said, my rewrite man on the other end dissolved. He couldn’t go on. They had to put another rewrite man on.

AP Log Bob Ford held an open line to the office. Then Val Imm, society editor of the Times-Herald, came bursting through a mob of newsmen, grabbed an adjoining phone, shouted into it. Ford relayed her words . . .

SMITH Telephones were at a premium in the hospital and I clung to mine for dear life. I was afraid to stray from the wicket lest I lose contact with the outside world. My decision was made for me, however, when Kilduff and Wayne Hawks . . . ran by me, shouting that Kilduff would make a statement shortly in the so-called nurses room a floor above and at the far end of the hospital. I threw down the phone and sped after them. We reached the door of the conference room and there were loud cries of “Quiet!”

KILDUFF I got up there and I thought, “Well, this is really the first press conference on a road trip I have ever had to hold.” I started to say it, and all I could say was “Excuse me, let me catch my breath,” and I thought in my mind, “All right, what am I going to say, and how am I going to say it?” I remember opening my mouth one time and I couldn’t say it, and I think it must have been two or three minutes.

DUGGER Kilduff came into the classroom and stood on the dais before the bright green blackboard, his voice, too, vibrating from his feelings. “President John F. Kennedy—” he began. “Hold it,” called out a cameraman. “President John F. Kennedy died at approximately one o’clock Central Standard Time today here in Dallas. He died of a gunshot wound in the brain. I have no other details regarding the assassination of the President. Mrs. Kennedy was not hit. Governor Connally was hit. The Vice President was not hit.” Had President Johnson taken the oath of office? “No. He has left.” On that, Kilduff would say no more. As Kilduff lit a cigarette, the flame of his lighter quivered violently.

DONOVAN There was a brief flurry of questioning among the reporters themselves in the press room as to whether Johnson would take the oath there or take it in Washington, and the consensus immediately prevailed, of course, he would take it in Dallas, because in the kind of world we are living in, you can’t have the United States without a President, even in the time it takes to get from Dallas to Washington.

SMITH I raced into a nearby office. The telephone switchboard at the hospital was hopelessly jammed. I spotted Virginia Payette, wife of UPI’s Southwestern division manager and a veteran reporter in her own right. I told her to try getting through on pay telephones on the floor above. Frustrated by the inability to get through the hospital switchboard, I appealed to a nurse. She led me through a maze of corridors and back stairways to another floor and a lone pay booth. I got the Dallas office. Virginia had gotten through before me.

WICKER The search for phones began. Jack Gertz, traveling with us for A.T.&T., was frantically moving them by the dozen into the hospital but few were ready yet. I wandered down the hall, found a doctor’s office, walked in, and told him I had to use the phone. He got up without a word and left. I battled the hospital switchboard for five minutes and finally got a line to New York. . . . The whole conversation with New York probably took three minutes. Then I hung up, thinking of all there was to know, all there was I didn’t know. I wandered down a corridor and ran into Sidey and Chuck Roberts of Newsweek. They’d seen a hearse pulling up at the emergency entrance and we figured they were about to move the body. We made our way to the hearse—a Secret Service agent who knew us helped us through suspicious Dallas police lines—and the driver said his instructions were to take the body to the airport. That confirmed our hunch, but gave me, at least, another wrong one. Mr. Johnson, I declared, would fly to Washington with the body and be sworn in there. We posted ourselves inconspicuously near the emergency entrance. Within minutes they brought the body out in a bronze coffin. . . . Mrs. Kennedy walked by the coffin, her hand on it, her head down, her hat gone, her dress and stockings spattered. She got into the hearse with the coffin. The staff men crowded into cars and followed. That was just about the only eyewitness matter that I got with my own eyes that entire afternoon. Roberts commandeered a seat in a police car and followed, promising to “fill” Sidey and me as necessary. We made the same promise to him and went back to the press room.

DAVIS Jiggs Fauver, of the White House transportation office, grabbed my arm and said, “Come with me. We need a pool. Don’t ask any questions.” I grabbed my typewriter and left.

SMITH I ran back through the hospital to the conference room. There Jiggs Fauver . . .

grabbed me and said Kilduff wanted a pool of three men immediately to fly back to Washington on Air Force One, the Presidential aircraft. “He wants you downstairs, and he wants you right now,” Fauver said. Down the stairs I ran and into the driveway, only to discover Kilduff had just pulled out in our telephone car. Charles Roberts . . . Sid Davis and I implored a police officer to take us to the airport in his squad car. On the way to the airport, the young police officer driving said, “I hope they don’t blame this on Dallas.” I don’t know who it was in the car that said, “They will.” The Secret Service had requested that no sirens be used in the vicinity, but the Dallas officer did a masterful job of getting us through some of the worst traffic I have ever seen. As we piled out of the car on the edge of the runway about 200 yards from the Presidential aircraft, Kilduff spotted us and motioned for us to hurry. We trotted to him and he said the plane could take two pool men to Washington; that Johnson was about to take the oath of office aboard the plane and would take off immediately thereafter. I saw a bank of telephone booths beside the runway and asked if I had time to advise my news service. He said, “But for God’s sake, hurry.” Then began another telephone nightmare. The Dallas office rang—busy. I tried calling Washington. All circuits were busy. Then I called the New York bureau of UPI and told them about the impending installation of a new President aboard the airplane.

WICKER In the press room we received an account from Julian Reed, a staff assistant, of Mrs. John Connally’s recollection of the shooting. . . . The doctors had hardly left before Hawks came in and told us Mr. Johnson would be sworn in immediately at the airport. We dashed for the press buses, still parked outside. Many a campaign had taught me something about press buses and I ran a little harder, got there first, and went to the wide rear seat. That is the best place on a bus to open up a typewriter and get some work done. On the short trip to the airport, I got about 500 words on paper—leaving a blank space for the hour of Mr. Johnson’s swearing-in, and putting down the mistaken assumption that the scene would be somewhere in the terminal.

SMITH Kilduff came out of the plane and motioned wildly toward my booth. I slammed down the phone and jogged across the runway. A detective stopped me and said, “You dropped your pocket comb.”. . . Kilduff propelled us to the President’s suite two-thirds of the way back in the plane. . . . I wedged inside the door and began counting. There were 27 people in this compartment.

DAVIS The Judge, Mrs. Sarah Hughes, of Dallas, told the President to raise his right hand and repeat after her. Then he repeated the oath. At that moment, I started the second hand on my watch and I clocked it at 28 seconds.

SMITH The two-minute ceremony concluded at 3:38 p.m. EST and seconds later, the President said firmly, “Now, let’s get airborne.” Col. James Swindal, pilot of the plane, a big gleaming silver and blue fan-jet, cut on the starboard engines immediately. Several persons, including Sid Davis of Westinghouse, left the plane at that time. The White House had room for only two pool reporters on the return flight and these posts were filled by Roberts and me, although at the moment we could find no empty seats. At 3:47 p.m. EST the wheels of Air Force One cleared the runway.

WICKER As we arrived at a back gate along the airstrip, we could see Air Force One, the Presidential jet, screaming down the runway and into the air.

DUGGER The details were given to us by a pool reporter, Sid Davis. . . . I shall not soon forget the picture in my mind, that man standing on the trunk of a white car, his figure etched against the blue, blue Texas sky, all of us massed around him at his knees as he told us what had happened in that crowded compartment in Air Force One.

WICKER He and Roberts—true to his promise—had put together a magnificent “pool” report on the swearing-in. Davis read it off, answered questions, and gave a picture that so far as I know was complete, accurate and has not yet been added to.

The Reporter In Washington, reporters at a loss to “cover” the event hung around the White House pressroom and concentrated partly by habit and partly by duty on trivial details. Lyndon Johnson, they were informed by a briefer in Pierre Salinger’s office, had left Dallas at 2:47 Central Standard Time. Was that 2:47? Yes, 2:47. He had been sworn in to office aboard the plane by U.S. District Judge Sarah T. Hughes. Could the briefer spell that? Yes, Sarah had an “h.” In midafternoon Senator Hubert Humphrey stopped in at the White House and consented to an informal chat with newsmen. There was almost nothing to ask him. Did he see any significance in the fact that it had happened in Dallas? came one idiotic try. Humphrey was taken aback. He shook his head abruptly and he left. Those White House aides familiar to reporters were too stricken to be questioned, even if there had been questions to ask. “I’m sorry,” was the most anyone could say. Everywhere there was silent unease at the inability to locate the source of government, to know even where government was. It was reflected in the compulsive scuttling of reporters from one place to another where they could only observe arrivals and departures.

WICKER Kiker and I ran a half-mile to the terminal, cutting through a baggage-handling room to get there. I went immediately to a phone booth and dictated my 500-word lead, correcting it as I read, embellishing it too. Before I hung up I got Harrison Salisbury and asked him to cut into my story whatever the wires were filing on the assassin. There was no time left to chase down the Dallas police and find out those details on my own. Dallas Love Field has a mezzanine running around its main waiting room; it is equipped with writing desks for travelers. I took one and went to work. My recollection is that it was then about 5 p.m. New York time.

SMITH It was dark when Air Force One began to skim over the lights of the Washington area, lining up for a landing at Andrews Air Force Base. The plane touched down at 5:59 p.m. EST. I thanked the stewards for rigging up the typewriter for me, pulled on my raincoat and started down the forward ramp. Roberts and I stood under a wing and watched the casket being lowered . . . we were given seats on another ’copter bound for the White House lawn.

The Reporter It was not quite relief but at last a sense of location, of reality, that came on the South Lawn of the White House later in that strangely balmy evening. With terrific noise and lots of wind, resembling a monstrous wasp, the brown army helicopter bearing President Johnson bore down on the White House, hovered a moment, and then came to rest on the floodlit lawn . . . almost at once the exchange of gossipy desperate questions among reporters was altered. The known, manageable Washington seemed to return with Johnson. Where was he going? reporters now demanded. Who was he seeing? What was the President going to do?

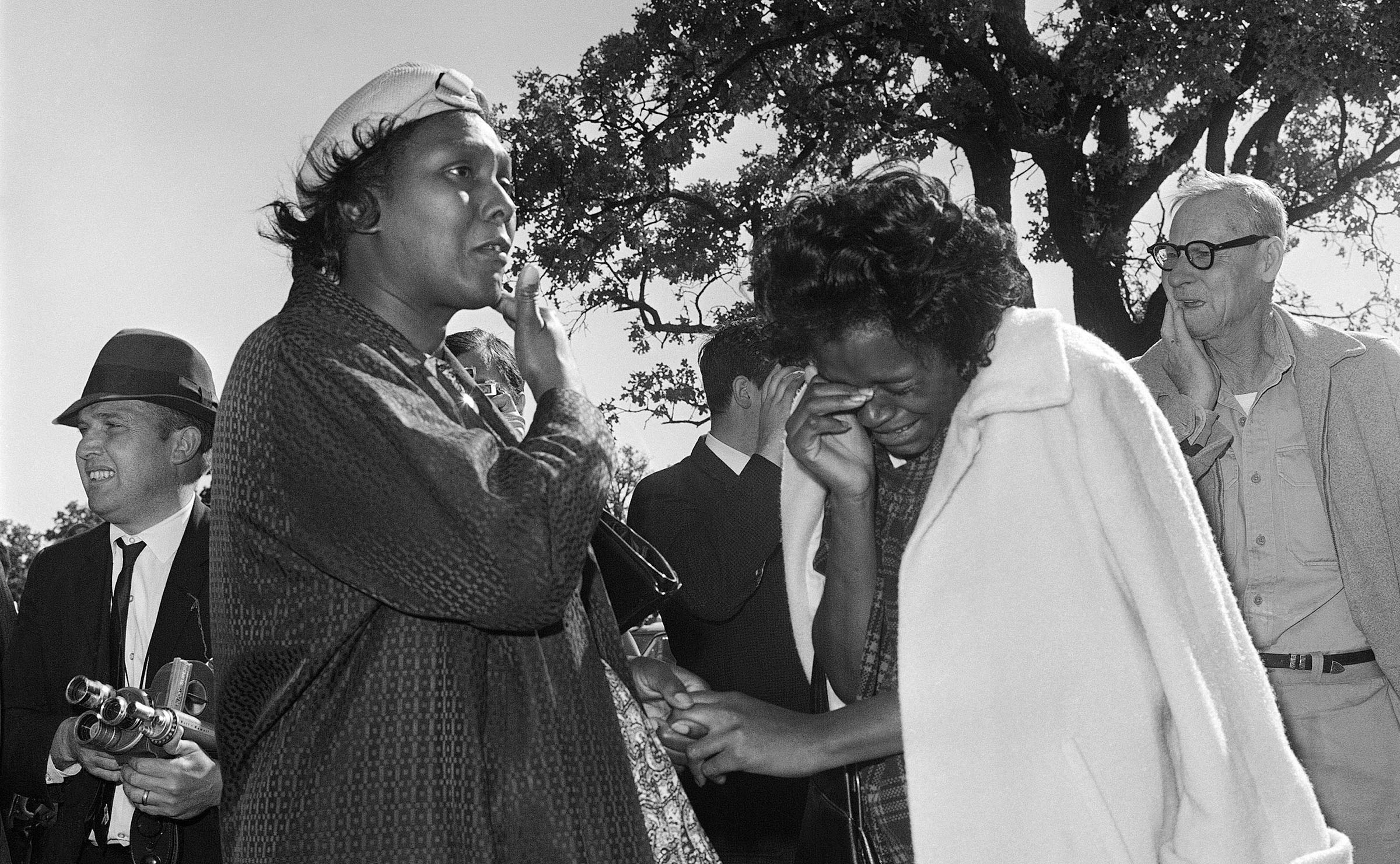

TOP IMAGE: Women in Dallas, November 22, 1963; AP Photo/File